Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

[ad_1]

Getty Images

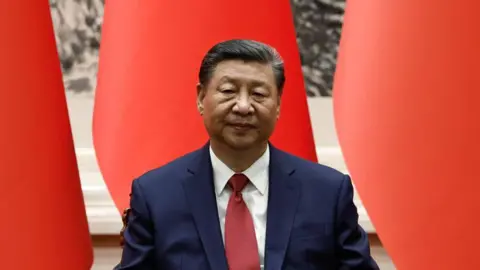

Getty ImagesAccording to founding leader Mao Zedong and current president Xi Jinping, the People’s Republic of China possesses a “magic weapon.”

It’s called the United Front Department of Labor – and it’s as alarming in the West as Beijing’s growing military arsenal.

Yang Tengbo, a famous businessman who was associated with Prince Andrewis the latest overseas Chinese national to be scrutinized – and sanctioned – for his ties to the UFWD.

The existence of the department is far from a secret. A decades-old and well-documented branch of the Chinese Communist Party, it has been controversial in the past. Investigators from the US to Australia have cited the UFWD in numerous espionage cases, often accusing Beijing of using it for foreign interference.

Beijing has rejected all allegations of espionage, calling them ridiculous.

So what is UFWD and what does it do?

A united front — originally referring to a broad communist alliance — was once cited by Mao as the key to the Communist Party’s triumph in China’s decades-long civil war.

After the war ended in 1949 and the Party began to rule China, the activities of the United Front receded and faded into the background. But in the last decade under Xi Jinping, the United Front has experienced a renaissance of sorts.

Xi’s version of the United Front is broadly in line with previous incarnations: “to build the broadest coalition with all relevant social forces,” according to Mareike Ohlberg, a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund.

At first glance, the UFWD isn’t shady — it even has a website and reports on many of its activities. But the scope of his work – and its reach – is less clear.

Although much of this work is domestic, Dr Ohlberg said that “the key target that has been identified for United Front work is overseas Chinese”.

Today, UFWD seeks to influence public debate on sensitive issues ranging from Taiwan, which China claims as its territory, to the suppression of ethnic minorities in Tibet and Xinjiang.

It also tries to shape narratives about China in foreign media, target critics of the Chinese government abroad, and co-opt influential Chinese figures from abroad.

“United Front’s work may involve espionage, but (it’s) broader than espionage,” Audrey Wong, an associate professor of politics at the University of Southern California, told the BBC.

“Besides the act of obtaining secret information from a foreign government, the activities of the United Front focus on the broader mobilization of Chinese people abroad,” she said, adding that China is “unique in the scale and scope” of such influence activities.

Reuters

ReutersChina has always sought such influence, but its growth in recent decades has given Beijing the opportunity to use it.

Since Xi became president in 2012, he has been particularly active in crafts China’s message to the worldencouraging confrontation “Wolf Warrior” approach to diplomacy and urged his country’s diaspora to “tell China’s story well.”

The UFWD operates through various overseas Chinese community organizations that have strongly defended the Communist Party abroad. They censored anti-CCP artwork and protested the activities of the Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama. UFWD has also been linked to threats against persecuted minorities abroad, such as Tibetans and Uyghurs.

But much of the UFWD’s work intersects with other party agencies, which operate under what observers have called “plausible denial.”

It is this obscurity that causes so much suspicion and apprehension about the UFWD.

When Ian appealed his ban, the judges agreed with the then-Secretary of State’s report that Ian “poses a danger to national security,” citing his downplaying of his ties to the UFWD as one of the reasons that led them to that conclusion.

Ian, however, maintains that he did nothing illegal and that the spy accusations are “totally untrue.”

Delivered

DeliveredCases like Young’s are becoming more common. In 2022, British Chinese lawyer Christine Lee was accused by MI5 of acting through the UFWD to establish relationships with influential people in the UK. The following year, Liang Litang, a US citizen who ran a Chinese restaurant in Boston, was charged with providing information about Chinese dissidents in the area to his contacts at the UFWD.

And in September, Linda Sun, a former aide in the New York governor’s office, was accused of using her position to serve the interests of the Chinese government – receiving benefits in return, including travel. According to Chinese state media reports, in 2017 she met with a senior UFWD official who ordered her to “be an ambassador for China-US friendship.”

It is not uncommon for famous and successful Chinese to be associated with a party whose approval they often need, especially in the business world.

But where is the line between influence peddling and espionage?

“The line between influence and espionage is blurred” when it comes to Beijing’s operations, said Ho-fung Hung, a politics professor at Johns Hopkins University.

This ambiguity has increased since China passed a law in 2017 requiring Chinese citizens and companies to cooperate with intelligence agencies, including sharing information with the Chinese government – a move that Dr. Hung said “effectively turns everyone into a potential spy.” .

The Ministry of State Security has released dramatic propaganda videos warning the public that foreign spies are everywhere and “they are cunning and insidious”.

Some students sent on special trips abroad were ordered by their universities to limit contact with foreigners and asked to report on their activities upon their return.

And yet Xi seeks to promote China in the world. So he tasked the party’s trust group with projecting power abroad.

And this becomes a challenge for Western powers – how will they balance doing business with the world’s second largest economy alongside serious security concerns?

Real fears about China’s influence abroad are fueling hawkish sentiment in the West, often putting governments in a quandary.

Some, like Australia, tried to protect themselves with new foreign interference laws which criminalize persons considered to be interfering in internal affairs. In 2020, the US imposed visa restrictions on people deemed to be active in UFWD activities.

A furious Beijing has warned that such laws – and the prosecutions they have sparked – are hampering bilateral relations.

“The so-called accusations of Chinese espionage are absolutely absurd,” a foreign ministry spokesman told reporters on Tuesday when asked about Yang. “The development of Sino-British relations serves the common interests of both countries.”

Some experts say the long arm of China’s United Front is indeed a cause for concern.

“Western governments now need to be less naive about the work of the United Front of China and see it as a serious threat not only to national security, but also to the safety and freedom of many ethnic Chinese,” says Dr. Hung.

But, he adds, “governments must also be vigilant against anti-Chinese racism and work hard to build trust and cooperation with ethnic Chinese communities in jointly confronting the threat.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLast December, Di San Duong, a Vietnamese-born leader of Australia’s ethnic Chinese community, was convicted of foreign interference planning for trying to coddle an Australian minister. Prosecutors argued he was an “ideal target” for the UFWD because he ran for office in the 1990s and boasted of ties to Chinese officials.

Duong’s trial focused on what he meant when he said the minister’s participation in a charity event would benefit “us Chinese” – did he mean the Chinese community in Australia or mainland China?

Ultimately, Duong’s conviction – and prison sentence – raised serious concerns that such broad anti-espionage laws and prosecutions could easily become weapons to target ethnic Chinese.

“It is important to remember that not all ethnic Chinese are supporters of the Chinese Communist Party. And not everyone involved in these diaspora organizations is driven by passionate loyalty to China,” says Dr. Wong.

“An overly aggressive policy based on racial profiling will only legitimize the Chinese government’s propaganda that ethnic Chinese are not welcome and ultimately push the diaspora further into Beijing’s embrace.”

[ad_2]

Source link