Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC AFRICA, Lagos health correspondent

Gets the image

Gets the imageAt the age of 24, Napis Salah threatened to become just another statistics in Nigeria, where a woman dies on average, giving birth every seven minutes.

Working during the strike by doctors, which, despite their stay in the hospital, was not helping experts as soon as complications arose.

Her baby’s head was stuck, and she was just told to lie down during the childbirth, which lasted for three days.

In the end, Caesarean was recommended and a doctor who was ready to carry out it was located.

“I thanked God because I almost die. I have no strength left, I have nothing left,” the BBC says from the state of Cano in the north.

She survived, but tragically her baby died.

Eleven years she returned to the hospital to give birth several times and is engaged in a fatalistic attitude. “I knew (every time) that I was between life and death, but I was no longer afraid,” she says.

Ms Salah’s experience is not unusual.

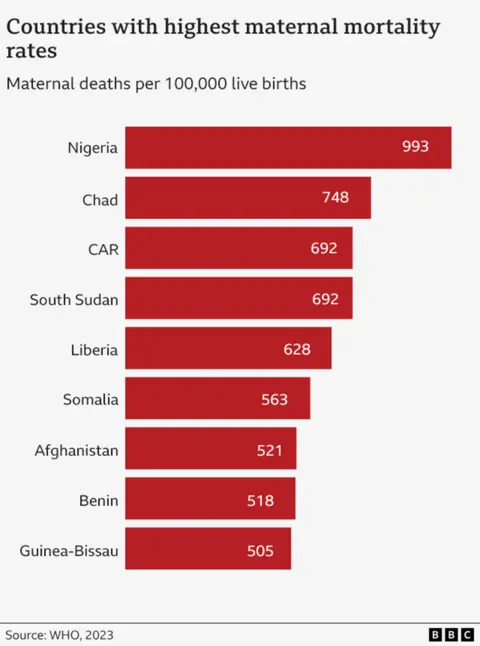

Nigeria is the most dangerous nation in the world in which you can give birth.

As depending on Recent UN estimates for the countryMade since 2023, each of the 100 women dies in childbirth or in the following days.

This puts it at the top of the league table that does not want to govern the country.

In 2023, Nigeria was more than a quarter – 29% – all deaths from mothers around the world.

This is estimated by 75,000 women who die in childbirth a year that works in one death every seven minutes.

Warning: This article contains an image that shows childbirth

Henry Ede

Henry EdeDisappointment for many is that a large number of deaths – from things such as bleeding after delivery (known as postpartum hemorrhage) – can be prevented.

Chinenye Nweze was 36 years old when she went to death in the Southeast city of Onitha five years ago.

“The doctor needed blood,” recalls her brother Henry Ede. “They were not enough, and they ran. Losing my sister, and my friend is nothing I would like to the enemy. The pain is unbearable.”

Other common causes of mother’s death are an obstacle, high blood pressure and dangerous abortions.

According to Martin Dolsten from the UN Children’s Organization, UNICEF, the “very high” level of mother’s maternal mortality is the result of a combination of a number of factors.

Among them, he said, poor health infrastructure, physicians’ deficiency, expensive treatments that many cannot afford cultural practices that can lead to some distrustful healthcare professionals and uncertainty.

“No woman deserves death when he was born with a child,” says Maybl Onwuen, the national coordinator of the Women’s Development Fund.

She explains that some women, especially in the countryside, believe that “the visit to the hospitals is a full waste” and choose “traditional remedies and not seek medical care, which can hold rescue assistance.”

For some, it is almost impossible to get to the hospital or the clinic because of the lack of transport, but Mrs. Otwuen believes that even if they succeeded, their problems would not end.

“Many health care facilities lack the main equipment, materials and staff prepared, which makes it difficult to provide quality service.”

The Nigeria Federal Government is currently spending only 5% of its health budget – a very insufficient up to 15% of the target involved in the 2001 African Union Treaty.

In 2021, there were 121,000 midwives for the population of 218 million, and less than half of all births were controlled by a qualified healthcare provider. It is estimated that 700,000 nurses and midwives need 700,000 nursing and midwives to meet the recommended health care relationship in the country.

There is also a serious lack of doctors.

The staff and objects deficit postpone some of the search for professional assistance.

“I honestly do not trust hospitals, there are too many negligence stories, especially in public hospitals,” Jamila Ihak says.

“For example, when I had a fourth baby, there was complications during the birth. The local duty advised us to go to the hospital, but when we arrived there, no healthcare provider was to help me. I had to return home, and I eventually gave birth,” she explains.

A 28-year-old Kano guy is waiting for his fifth child.

She adds what will think to go to the private clinic, but the price is not permeable.

Chinwendu obiejesi, who is waiting for his third child, will be able to pay for private medical care at the hospital and “don’t think to give birth anywhere else.”

He says that among her friends and family the death of the mother is rare now, whereas she has heard of them quite often.

She lives in the wealthy suburb of Abuja, where it is easier to get hospitals, the roads are better and the work on emergency services. More and more women in the city are also educated and are aware of the importance of going to the hospital.

“I always visit women’s help … It allows me to talk to doctors regularly, do important tests and scan, and track both my health and baby,” says BBC Mrs. Obiessi.

“For example, during my second pregnancy, they expected that I could bleed a lot, so they have prepared additional blood if the transfusion was needed. Fortunately, I don’t need it, and everything went well.”

However, her family friends were unlucky.

During her second work, “Birth could not deliver the baby and tried to pull it out. The baby died. As long as she was sent to the hospital, it was too late. She still had to move surgery to deliver the baby’s body. It was a broken heart.”

Gets the image

Gets the imageDr. Nano Sando-Bakar, Director of Health Services at the National Primary Aid Development Agency in the country (NPHCDA), acknowledges that the situation is terrible, but says the new plan is to resolve some issues.

Last November, the Nigeria government launched a pilot phase of an innovative mortality rate (Mamii). In the end, this will be aimed at 172 local self -government districts in 33 states, which make up more than half of all childbirth -related deaths.

“We identify every pregnant woman, know where she lives, and support her through pregnancy, childbirth and further,” says Dr. Sando-Bacar.

So far, 400,000 pregnant women in six states were found in a home survey, “with the details of whether or not they attend anti -natal (classes).”

“The plan is to start binding them with the services to make sure they will receive help (they need) and to provide them safely.”

Mamii will seek to work with local transport networks to try to attract more women to the clinic, as well as urge people to subscribe to inexpensive public health insurance.

It is too early to say whether this influence has had this, but the authorities hope the country may eventually follow the trend of the rest of the world.

In the world match, the mother’s death decreased by 40% since 2000, due to the extension of access to health care. The number also improved in Nigeria over the same period – but only 13%.

Despite Mamii and other programs, there were welcome initiatives, some experts believe that it should be made more – including bigger investments.

“Their success depends on sustainable funding, effective implementation and constant monitoring to ensure achieving the assigned results,” says Mr. Dolsten UNICEF.

At the same time, the loss of each mother in Nigeria – 200 every day – will still be a tragedy for families.

For Mr. Edech grief from the loss of his sister is still raw material.

“It rose to become our anchor and the basis because we lost our parents when we grew up,” he says.

“At my lonely time when she crosses my mind. I’m crying bitterly.”

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC