Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

[ad_1]

BBC/Fred Scott

BBC/Fred ScottSaidnaya Prison is located on the Forbidden Hill about half an hour’s drive from the center of Damascus.

Over the past few days, the entrance has been repainted in the green, white and black Syrian revolutionary flag. The new colors did not dispel the ominous atmosphere of the place.

As I passed through the gates, I thought of the despair that must have gripped the thousands of Syrians who had made the same journey.

According to one estimate, more than 30,000 detainees have been killed in Saidnaya in the years since the start of the Syrian war in 2011. This is a large part of the more than 100,000 people, almost all men, but including thousands of women, as well as children – who disappeared without a trace in Bashar al-Assad’s Gulag.

Other parts of Assad’s prison system were less harsh. Phone calls to the house were allowed and families were allowed to visit.

But Saydnaya was the dark and rotten heart of the regime. The fear of being sent there and killed without knowing what happened was central to the Assad regime’s system of coercion and repression.

The authorities did not have to notify the families who were imprisoned there. Allowing them to fear the worst was another way of applying pressure. The regime has a boot on Syrians’ throats because of the power, reach and savagery of its countless and overlapping secret services, as well as the routine use of torture and executions.

I have been to other infamous prisons in the days since their release, including Abu Salim Prison, former Libyan leader Colonel Gaddafi’s infamous prison in Tripoli, and Puli Charki outside Kabul, Afghanistan.

None of them were as vile and harmful as Saydnaya. In its overcrowded cells, men had to urinate into plastic bags because their access to toilets was limited.

When the locks were broken, they left behind their dirty rags and scraps of blankets, which they all kept to cover themselves when they slept on the floor. Torture and executions have already been recorded in Saydnaya.

Undoubtedly, in the coming months, more information will emerge from the mouths of former prisoners about the horrors that took place within its walls.

In the corridors of Saidnaya, you see how difficult it will be to fix the country that Assad has broken to save his regime. Now that the prison has been hacked, like the country, it has become a microcosm of all the problems facing Syria since the Assad regime collapsed and was swept away.

One of the challenges is documenting what the regime did to its victims. In a sign of how far Syria has come in just a week, volunteers went to the prison to try to preserve Saydna’s records.

Papers are scattered in offices and even on the concrete floor of the prison yard. Families pick through files and sheets of tattered documentation, trying to find a name, date or place they recognize.

The mess of the records looks like someone tried to destroy what was done here in the name of Bashar al-Assad’s Syria. When dictators and their henchmen fall, making sure they don’t take the truth with them is a big part of a better future.

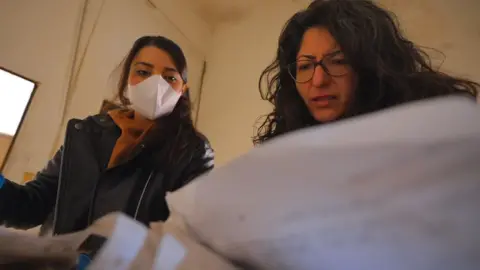

BBC/Fred Scott

BBC/Fred ScottA musician named Safana Buckle gave her group of volunteers face masks and blue nitrile gloves, along with instructions on how to take pictures and collect documents.

Safana admitted they were amateurs and said they were taking matters into their own hands because there were no international human rights groups and evidence and documents were disappearing.

“Even if one family gets one answer that their loved one is gone, dead, or died in the hospital, that’s enough for me,” Safana told me. “It’s very chaotic… Where are the international sources supposed to document all this chaos?”

It’s not just about the families getting some kind of release, at least knowing what happened to the missing. One day there may be trials of criminals. Documents are evidence.

BBC/Fred Scott

BBC/Fred ScottThe truth that the volunteers discovered with their own eyes shocked them. All Syrians knew prisons were bad, but Saydnaya was much worse than they expected. Widad Halabi, one of the volunteers, took off her mask and broke down in tears after searching the cells for evidence for about an hour.

“What I saw here was a life unfit for humans. I imagined how they lived, their clothes. How did they breathe? How did they eat? How did they feel?

“It’s terrible… terrible. There are bags of urine on the floor. They couldn’t go to the toilet, so they had to pour their urine into bags. Smell. No sun, no light. I can’t believe that people lived here when we lived and breathed normal life.’

It will be difficult for the Syrians and their new rulers to track down the people they want to punish. Bashar Assad and his family fled to Russia. His brother Maher, who has the same reputation for violence and corruption as the rest of his extended family, is believed to be in Iraq.

Several of Assad’s cousins clashed with rebel fighters as they tried to flee to Lebanon. One of them, as reported by Reuters, was killed in a shootout.

When I entered Syria a week ago, hundreds of cars filled with distraught and frightened families connected to the regime, who believed they would be in danger in the new Syria, were queuing up to cross the border into Lebanon. Meanwhile, hundreds were driving in the opposite direction, desperate to get home.

There may eventually be a trial to prosecute Bashar al-Assad, his family members and some of those who have carried arms for the regime. Gathering evidence will be part of that. But the exodus in the final hours of the regime and the confused days and nights that followed means it will be difficult to get to the people responsible.

At Saidnaya Prison, families roam the building, desperate for information, looking for those they lost, horrified by what they see. Just being in the cells and corridors of Saidnaya, freezing in December, reinforces the widespread desire to see the punishment of all those involved in the crimes of the Assad regime.

A group of men gathered in the prison yard, silently smoking, some flipping through files picked up from the ground. Everyone I spoke to said that the future must be built on justice towards the past. The men in the group who were searching for the missing, sons, brothers and cousins, called Saydnaya a mass grave. They want Bashar al-Assad’s head, literally. They whispered as one of them said he should be beheaded.

One of them, a young man named Ahmed, said he knew the brother he was looking for was alive because he could see him in a dream. Ahmed himself spent three years in Saidnaya.

“It was so bad, the torture, the food, everything. We suffered.”

BBC/Fred Scott

BBC/Fred ScottMohammed Khalaf, an elderly man, has been searching for his son Jabr since he was dragged from the family’s breakfast table by thugs from one of the state intelligence services in 2014.

“There are many of us. People came from Qamishli, Hasaki, Deir al-Zoura, Al-Raqi in search of our loved ones. Thousands are still on the streets looking for their children. It’s not just me.”

Inside one of the cell blocks, young men from Aleppo warmed themselves over a fire they had lit in a metal tin, burning old prison uniforms scattered around each cell. They were looking for brothers who were detained and then disappeared.

Like many others searching for information or a body in Saidnaya, the men had no money for a hotel. So they camped out in the prison where they believe their brothers were imprisoned and most likely killed.

One of the people from Aleppo, Ezzedine Khalil, wants to get news about his brother, who was captured by the regime on September 1, 2015. They all know the exact dates.

“We don’t know if he is alive or dead. If he is dead, they must give us his body. They have to tell us if he is dead. We just want to know. We want to know what to do next.”

His friend Mohammed Radvan was looking for his brother and cousin who were detained in 2012. There were rumors that the night before the fall of the regime, 22 freezer trucks were brought to the prison to remove the bodies. The rumors were not confirmed, but Mohammed and Ezzedine were convinced of their truth.

Mohammed looked exhausted and his anger flared. He turned to Assad.

“Where are you pig, 22 refrigerators of separation? All those who participated in this crime and all those who served her in Saidnaya prison must be brought to justice. Everyone! Even if they were working on cleaning. Everyone should be involved. to the account”.

“Because if they knew what was going on, they should have at least told the families of the prisoners that their relatives were killed, stabbed, hanged or tortured.”

Both men ended with the Islamic prayer, “Allah is sufficient for me, and He is the best manager of affairs.”

Their desire to punish Assad and his men could be one of the drivers of events in the next few months. Syrians want their executioners punished.

The extended Assad clan used Syria as their bank account. They helped themselves to get shares in enterprises that could bring profit. They controlled the lucrative telecommunications and mobile communications market. While scrambling, Syrians have struggled to make ends meet in an economy ravaged by war and drained by rapacious and corrupt regime favourites. Syria’s new rulers inherited huge debts and an almost worthless currency. A couple of hundred dollars equals a plastic garbage bag with wads of Syrian pounds.

Corruption has spread to the prison system. Victims and families desperate to avoid years in the pit of hell were willing to pay big bucks to stay out.

Hassan Abu Shwarb served 11 years on death row for terrorism, which the Assad regime called insurgency. Hassan, a quiet man now 31, denies ever joining an armed group. Instead, he says he was detained at a government office while he was getting the paperwork he needed to get a passport so he could accept an offer to study in Canada.

His brother said the family paid a total of $50,000 (£39,509) in bribes on five separate occasions to try to get him out. In all cases, corrupt officials who offered help in exchange for cash pocketed the money without letting Hasan out. A couple of weeks before the collapse of the regime, another corrupt judge offered to release Hassan for another $50,000.

After his arrest, Hassan Abu Shwarb was tortured when he was held for 80 days in a military intelligence interrogation center. Among other injuries, the executioners broke one of his legs. Hassan says he was with one of his cellmates, a 49-year-old man, when he died after three days of torture. Jailors recorded death from a stroke.

Hassan was very happy to return home.

BBC/Fred Scott

BBC/Fred Scott“When my mother held me in her arms after I was 11, I can’t describe the feeling. There’s nothing better than being back in your home and neighborhood.”

But like many Syrians, Hassan’s optimism about the future begins with a determination that the regime’s leaders and associates must suffer for their actions.

“They should be punished. We are still human souls, not stones. And those who killed should be publicly executed. Otherwise, we will not survive it.

“We need to forget and move on. This is happiness for all Syrians. We need to get back to our work and responsibility to continue. We need to forget. We have turned the page. All sorrow is behind us.’

The leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham began using his real name, Ahmed al-Sharaa, instead of the wartime alias Abu Mohammed al-Jolani. The name change sends a message about looking ahead. Proof that Ahmed al-Sharaa will have to prioritize justice for the ousted regime if he doesn’t want chaos as the people take matters into their own hands.

The future is hard and the past is full of pain. Here in Damascus, it feels as if a collective burden has been lifted from the nation’s shoulders.

Syrians know how deep their problems are. To maintain the optimism engendered by the fall of Assad, Syrians want to see progress.

[ad_2]

Source link