Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC

BBCFor years, Russia and Syria have been key partners, with Moscow gaining access to Mediterranean air and naval bases and Damascus receiving military support in its fight against rebel forces.

Now, with the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, many Syrians want Russian troops out, but their interim government says it is ready for further cooperation.

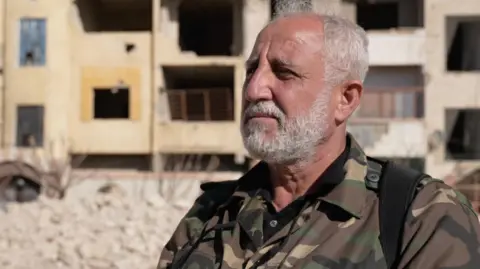

“Russia’s crimes here are beyond description,” said Ahmed Taha, a rebel commander in Douma, six miles northeast of the capital, Damascus.

The city was once a thriving place in the region known as the “bread basket” of Damascus. And Ahmed Taha was once a civilian working as a trader when he took up arms against the Assad regime after a brutal crackdown on protests in 2011.

Whole residential neighborhoods in Douma are now in ruins after some of the fiercest fighting in Syria’s nearly 14-year civil war.

Moscow entered the conflict in 2015 to support the regime as it was losing ground. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov later claimed that at the time of the intervention, Damascus was only a few weeks away from being captured by the rebels.

The Syrian operation showed Russian President Vladimir Putin’s desire to be taken more seriously after widespread international condemnation of his annexation of Crimea.

Moscow said it had tested 320 different types of weapons in Syria.

He also secured a 49-year lease on two military bases on the Mediterranean coast – the Tartus Naval Base and the Khmeimim Air Base. This allowed the Kremlin to quickly expand its influence in Africa, serving as a springboard for Russian operations in Libya, the Central African Republic, Mali and Burkina Faso.

Despite the support of Russia and Iran, Assad could not prevent the collapse of his regime. But Moscow offered him and his family asylum.

Many Syrian civilians and rebel fighters now see Russia as complicit with the Assad regime, which helped destroy their homeland.

“The Russians came to this country and helped the tyrants, the oppressors and the invaders,” says Abu Hisham, celebrating the fall of the regime in Damascus.

The Kremlin has always denied this, saying it only targets jihadist groups such as IS or al-Qaeda.

But the UN and human rights groups have accused the regime and Russia of committing war crimes.

In a 2016 assault on densely populated eastern Aleppo, Syrian and Russian forces launched relentless airstrikes, “claiming hundreds of lives and reducing hospitals, schools and markets to rubble,” according to a UN report.

In Aleppo, Douma and elsewhere, regime forces besieged rebel-held areas, cutting off food and medicine supplies, and bombarded them until armed opposition groups surrendered.

Russia has also negotiated ceasefires and surrender agreements for rebel-held towns such as Douma in 2018.

Ahmed Taha was among the rebels who agreed to surrender in exchange for safe exit from the city after a five-year siege by the Syrian army.

He returned to Douma in December as part of a rebel offensive led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and its leader Ahmed al-Sharaa.

“We returned home in spite of Russia, in spite of the regime and all those who supported it,” says Taha.

He has no doubts that the Russians should leave: “Russia is our enemy.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by many of the people we talk to.

Even the leaders of the Christian communities of Syria, whom Russia has sworn to protect, say that they received little help from Moscow.

In Bab Touma, the ancient Christian quarter of Damascus, the Patriarch of the Syrian Orthodox Church says: “We have had no experience of Russia or anyone else from the outside world protecting us.”

“The Russians were here for their own convenience and purposes,” Ignat Afrem II tells the BBC.

Other Syrian Christians were less diplomatic.

“When they came in the beginning, they said, ‘We came here to help you,'” says a man named Asad. “But instead of helping us, they destroyed Syria even more.”

AFP

AFPSharaa, now the de facto leader of Syria, said in a BBC interview last month that he will does not rule out the possibility of the Russians staying, and he called the relationship between the two countries “strategic.”

Moscow seized on his words, and Foreign Minister Lavrov agreed that Russia “has a lot in common with our Syrian friends.”

But untangling the ties in a post-Assad future may not be easy.

Rebuilding the Syrian armed forces will require either a completely new start or remaining dependent on Russian supplies, which would mean at least some kind of relationship between the two countries, says Turki al-Hassan, a defense analyst and retired Syrian army general.

Hassan says that Syria’s military cooperation with Moscow dates back to before the Assad regime. Almost all the equipment it has was manufactured by the Soviet Union or Russia, he explains.

“From the beginning, the Syrian army was armed with Eastern Bloc weapons.”

Between 1956 and 1991, Syria received from Moscow about 5,000 tanks, 1,200 fighter jets, 70 ships and many other systems and weapons worth more than $26 billion (£21 billion), according to Russian estimates.

Much of this was in support of Syria’s war with Israel, which has largely defined the country’s foreign policy since its independence from France in 1946.

More than half of this amount was not paid after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but in 2005 President Putin wrote off 73% of the debt.

For now, Russian officials have taken a conciliatory but cautious approach to the interim rulers who have ousted Russia’s longtime ally.

Moscow’s representative to the UN, Vasyl Nebenzia, said that the latest events marked a new stage in the history of what he called the “brotherly Syrian people”. He said Russia would provide both humanitarian aid and reconstruction support to allow Syrian refugees to return home.