Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Samira HusseinSouth Asia correspondent, BBC News, Delhi

BBC

BBCOn May 9, Nurul Amen talked to his brother. The call was short but the news was devastating.

He learned that his brother Kairul and four other relatives were among the 40 refugees, who allegedly deported the Indian government into Myanmar, the country they fled in fear years ago.

Myanmar is in the midst of a fierce civil war between the junta – which captured power in the 2021 coup – and ethnic militias and resistance forces.

The chances that Mr. Amein again see his family disappear.

“I couldn’t process the suffering that my parents and others faced,” said Mr. Amin, 24 years old, BBC in Delhi.

Three months after they were removed from the Indian capital, the BBC managed to contact the refugees in Myanmar. Most remain with the BA HTOO army (BHA), a resistance group fighting the military in the southwest of the country.

“We don’t feel safe in Myanmar. It’s a place is a complete military zone,” said soy nur on a video call made from BHA member. He talked to a wooden shelter with six other refugees around him.

The BBC collected testimony from refugees and accounts of relatives in Delhi and talked to experts who investigate the allegations to happen to them.

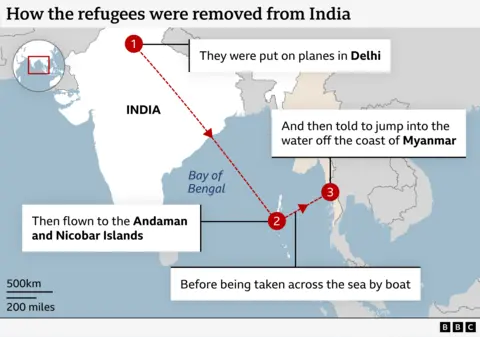

We learned that they flew from Delhi to the Island in the Bulf, wearing a military dishes and eventually forced the Andaman Sea with life Kurts. They then made their way ashore and now confronted with an uncertain future in Myanmar that fled mainly the Muslim community of Rohinj in a huge amount in recent years to avoid persecution.

“They tied our hands, covered our faces and brought us as captives (on the boat). Then they threw us into the sea,” said John, one of the men in the group, told his brother on the phone shortly after reaching the earth.

“How can someone just throw people into the sea?” asked Mr. Amen. “Humanity lives in the world, but I have not seen any humanity in the Indian government.”

Thomas Andrews, a UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Myanmar, says there is “important evidence” confirming the allegations he presented to the head of the Indian mission in Geneva but will not yet receive the answer.

The BBC also addressed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of India several times, but did not hear during the publication.

The shareholders often indicated that the state of the Rohinji in India is unstable. India does not recognize Rokhinga refugees, but rather as illegal immigrants acting in the country’s foreigners.

In India, there is a significant population of Rokhondji refugees, albeit Bangladesh, where more than a million lives, has the largest number. Most escaped from Myanmar after the deadly army in 2017. Despite the fact that he lived there by generations, Rokhin was not recognized as citizens.

In India, 23,800 ROINGYA refugees are registered in India in the UN, the UN Refugee Agency. But Human Rights Watch suggests that the actual amount is 40,000.

Noorul Amin

Noorul AminOn May 6, refugees 40 Roaringya, who had cards for UNHCR refugee refugees and lived in different parts of Delhi, were taken to local police areas under the guise of collecting biometric data. This is an annual process provided by the Indian government, where Rokhondji refugees are photographed and fingerprints. A few hours later, they were taken to the Indian detention center in the city, BBC reported.

Mr. Amin says his brother called him and told him that he was being delivered to Myanmar and asked him to receive a lawyer and warn UNHCR.

On May 7, the refugees said they were taken to the Indan Airport, east of Delhi, where they sat in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Indian Gulf.

“After leaving the plane, we saw that two buses came to accept us,” Mr. Nuar said in a video call. He added that he could see the words “Bhartia Nausen” written on the side of the buses, the term Hindi, which refers to the India’s Military Fleet.

Gets the image

Gets the image“As soon as we reached the bus, they tied our hands with plastic material and covered our face with a black muslin fabric,” he said.

Although people on the buses did not identify themselves, they were dressed in military fatigue and talked to Hindi.

After short later After their hands were unleashed and their faces were revealed.

They describe dishes as a large warship with two floors, at least 150 m long (490 feet).

“A lot of people (people on the ship) were in T-shirts, pants with black and black army boots,” said Mohammad Sodjad, who was on a call with Mr. Nura. “They were not in the same thing in black, some in brown.”

Mr. Nuar says the group was on a military ship for 14 hours. They were given food regularly, traditional Indian rice tariff, lentils and panic (cheese).

Some men say they were under violence and humiliation on the ship.

“We were treated very badly,” said Mr. Nuar. “Some were very beaten. They were hit several times.”

In the video, Voya Vlata showed scars on the right wrist and repeatedly described that he had been hit and slapped on his back and faces, and pokes a bamboo rod.

“They asked me why I was illegally in India, why are you here?”

Gets the image

Gets the imageRokhinga is a predominantly Muslim ethnic community, but of 40 people who are forcibly returned in May, 15 Christian ones.

Those who detained them in the way from Delhi even said, “Why didn’t you become Hindus? Why did you move from Islam to Christianity?” Mr. Nuar said. “They even made us lower our pants to find out whether we are cut or not.”

Another refugee, Eman Hussein, said the military accused him of participating in Molar massacreReferring to the attack on April 22, when 26 civilians, mostly Hindu tourists, were shot dead by militants in Kashmir, who released India.

The Indian government has repeatedly accused Pakistani citizens of pursuing attacks, and denied a statement. There was no opinion that Rohin had a connection with the shootings.

The next day, May 8, around 7:00 pm local time (12:30 GMT), refugees were ordered to go down the stairs on the side of the military dishes. Below they described, seeing four smaller rescue boats, black and made of rubber.

Refugees were forced to plant two boats, 20 on each and accompanied by several people who transport them. Two other boats that led the road had more than a dozen employees. They traveled with tied hands for more than seven hours.

“One of the boats with the military reached the seashore and tied a long rope to the tree. This rope was delivered to the boat,” said Mr. Nuar.

He said they were given life committees, their hands were unleashed – and they were told to jump into the water. “We held on to the rope and sailed more than 100 m to get to the shore,” he said, adding that they were told that they had reached Indonesia.

Then the people who took them there left.

The BBC was charged with the Indian government and the Indian fleet and did not answer.

A geeth image

A geeth imageIn the first hours of May 9, the group found local fishermen who told them they were in Myanmar. They allow refugees to use their phones to name their relatives in India.

For more than three months, BHA has been assisting refugees, providing food and asylum in the Taninthari region in Myanmar. But their families in India were horrified about fate in Myanmar.

The UN says the life of Rohinji’s refugee life “was at great risk when the Indian authorities forced (them) to the Andaman Sea.”

“I personally studied this very disturbing business,” Mr. Andrew said. He acknowledged that the amount he could share was limited, but he also “talked to eyewitnesses and was able to confirm these reports and establish that they were based.”

On May 17, Mr. Amin and another member of the refugee family, who were removed, filed a petition called by the Supreme Court of India to return them to Delhi, immediately stop similar deportations and offer compensation to all 40 people.

“It opened the country for the horror of the Rohundj deportation,” says Colin Honzalves, a senior supporter of the Supreme Court, which is arguing on behalf of the petitioners.

“The fact that you can throw a person in the sea with a rescue jacket in the military war area was that people automatically decided not to believe,” Mr. Gonzalves said.

In response to the motion, one judge of the Supreme Court on the bench called the allegations “bizarre ideas”. He also stated that the prosecution did not provide sufficient evidence to justify his requirements.

Since then, the court on September 29 has agreed to hear the arguments to decide whether it is possible to consider rockers as refugees or if they are illegal immigrants and are therefore subjected to deportations.

Considering that tens of thousands of refugees Rohondji live in India, it is unclear why so much effort was devoted to deportation of these 40 people.

“Nobody in India can understand why they did it except the poison against Muslims,” Mr. Gonzalves said.

Refugee treatment has directed a chill across the row community in India. Last year, its members claim that the Indian authorities had an increase in deportations. No official numbers to confirm this.

Some went hiding. Others, like Mr. Amen, are no longer sleeping at home. He sent his wife and three children to another place.

“In my heart there is only this fear that the Indian government will take us too and throw us into the sea anytime. And now we are afraid to leave our homes,” Mr. Amen said.

“These are the people in India not because they want to be,” Mr. Andrews from the UN said.

“They are there because of the terrible violence that happens in Myanmar. They are literally running for their lives.”

Additional Charlotte Sarra report in Delhi