Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC

BBCSurvivors of a dive boat that sank in the Red Sea say they were pressured to sign official witness statements in Arabic they could not understand and were translated with an English employee of the boat company.

They say the man also tried to get them to sign a waiver that said they were not accusing anyone of “criminal activity.”

The 11 survivors who spoke to the BBC also accused Egyptian authorities of trying to cover up what happened, saying investigators were determined to blame it on a large wave.

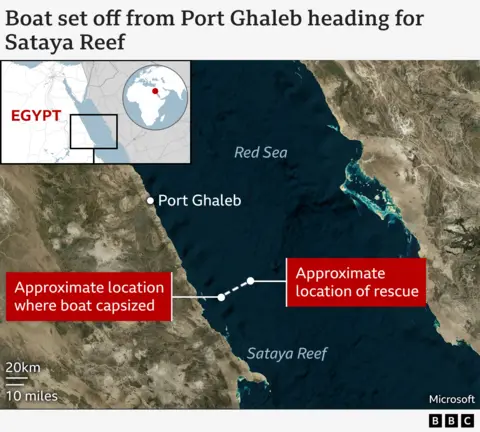

There were 46 people on board the Sea Story when it sank on the morning of November 25 last year – four bodies have been recovered and seven people are still missing, including two British divers.

Neither the Egyptian government nor the boat operators – Hurghada-based Dive Pro Liveaboard – responded to our questions.

on tuesday The BBC has uncovered several allegations of security breaches by survivors on board the vessel. A leading oceanographer who analyzed the weather data also said it was unbelievable that a huge wave hit the ship.

In the hours after being brought ashore, survivors say they were subjected to what one called “interrogation,” some from their hospital beds, by people they were told were judges.

Those who did not require hospital treatment were interviewed at a nearby resort, said other survivors who reported the same sense of pressure.

“We were told we couldn’t leave the room until they had taken everyone’s evidence,” says Sarah Martin, an NHS doctor in Lancashire.

The judges were part of an Egyptian investigation into what caused the sinking, although survivors say it was not clear exactly who was in charge.

Survivors say having their initial statements translated into Arabic by employees of the company that owns Sea Story was a clear conflict of interest.

Spanish diver Hisora Gonzalez said the man did not introduce himself to staff at first. “He just said, ‘You have to tell me what happened and then you have to sign this piece of paper.’

Only later, say several people we spoke to, did the man tell them he worked for Dive Pro Liveaboard.

Survivors say that after the man translated, their statements were given to investigators – something that shocked Lisa Wolfe. “A normal judge cannot take a translation from someone who is obviously fully involved in the process.”

Freudis Adamson

Freudis AdamsonOne survivor, a Norwegian police investigator, said she had “no idea” what the four pages of Arabic that were returned to her actually said. “They could write anything. I don’t know what I signed,” explained Fraidis Adamson. Under the signature, she writes that she could not get acquainted with the documents.

“We were so shocked and just wanted to go home,” Hisora said.

Representatives of the boat operators, Dive Pro Liveaboard, also repeatedly tried to get people to sign a waiver – survivors say – that would have seen them agree to the statement: “I am not accusing anyone of any criminal wrongdoing.”

Justin Hodges, an American diver who was also rescued, told us that a “disclaimer document” written in English was handed to him while he was testifying.

He said he thought the person he was talking to was an “official” but at that point he found out he was working for the company.

“He reached out to the authorities,” says Justin. “The fact that he was trying to get us to abdicate at that point was crazy to me.”

At least some of those we spoke to did not sign the document.

Lisa Wolf

Lisa WolfEveryone we spoke to said they had not been allowed to keep copies of their statements, but the BBC was told that some people had managed to translate documents using their phones. Many of them told us that key, incriminating details that they had communicated verbally were left out of the documents.

“Everything about the condition of the life rafts and safety issues on the boat disappeared,” Lisa says.

Sarah and Hisora reported the same. “They just put in whatever they wanted,” Hisora says.

Survivors also say that the authorities from the beginning seemed determined to blame the tragedy on a huge wave.

This is despite the fact that many of those who were rescued said the waves were not too big to prevent them from swimming. A leading oceanographer told the BBC that weather data from the nearest airport at the time strongly corroborated survivors’ memories.

Hisora asked if she would eventually be able to see a copy of the investigators’ final report, but said she was told there was no need. “(It’s like) they already knew the cause was the wave,” she says.

When she asked again, Hisora said she was told that “the sea is responsible for this.” She believes that the authorities have already made a decision before the investigation began.

Hisori’s concerns are shared by Sara, who says the judges were also “very keen” that the survivors should not blame anyone for the accident.

Several survivors say they were told that if they wanted to prosecute someone, they had to name a separate and specific crime they were accused of.

“Just because I couldn’t name the person and the crime doesn’t mean someone isn’t guilty,” Sarah says.

Dive Pro Liveaboard’s last attempt to get survivors to sign a waiver was when one group tried to leave for Cairo, Justin says.

Justin Hodges

Justin HodgesA company representative told the group that they had lost their passports at sea, that the documents they presented were permits to pass through checkpoints.

“But then I get to the bottom of it, and the last sentence is the same question about the release,” repeating what he said he was asked to sign when he testified as a witness.

Justin says he went to warn the others, and when he returned to the man he believed was trying to mislead him, the papers “magically disappeared” and were replaced by more official-looking documents.

“My blood boiled,” he says.

The BBC has not seen the waiver documents or copies of them.

Family and friends of two missing Britons, Jenny Cawson and Tariga Sinada, from Devon, say they have been receiving partial and inaccurate news from the Egyptian government.

For example, after the disaster, they say they were told that the boat had not been found – despite the fact that they saw survivors being brought ashore on TV. They demand an open investigation.

“It looks like the Egyptian authorities are doing everything they can to sweep this under the carpet,” says one friend, Andy Williamson. “They want to protect their tourism industry.”

In March, a fire on another Dive Pro Liveaboard boat, the Sea Legend, killed a German tourist.

Last year, the independent consultancy Maritime Survey International prepared a report on the safety of diving boats in the Red Sea. It inspected eight vessels, but not including those operated by Dive Pro Liveaboard, and found that none had a “scheduled maintenance system, safety management system or stability books”, which are critical documents to prevent capsizing .

He also found the design standards “poor as all vessels lack watertight bulkheads, doors and hatches”.

He concluded that no vessel was safe and that the dive boat industry in Egypt was “trading virtually unregulated”.