Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Old mwab

Old mwabFamous “Black Mountains” Zambia – huge piles of waste production that hinges the Copperbelt horizon – deeply personal for the old MVAB, one of the leading visual artists of the country.

“As children, we called it” Mu Despanco ” – that is,” in danger, “says MVAB BBC.

“” Black Mountain “is a place where you don’t have to go,” says a painter who was born and lived in a copper belt under 18.

“But we would have made your way – to choose wild fruits that have somehow rise there,” the artist recalls.

Nowadays, young people heading to Mu Drager are looking for snippets of copper ore in the rocky slag of these elevated landfills – the toxic heritage of the century production in Zambia, one of the largest copper and cobalt producers in the world.

They dig deep and winding tunnels – and highlight the rocks to sell mostly Chinese buyers who then extract copper.

It is hard, dangerous, often illegal and sometimes deadly work. But it can also be profitable – and in a region where youth unemployment is about 45%, for some young people this is the only way to reduce the ends.

Old mwab

Old mwabThe latest work of MWABA – at the Lusaki National Museum this month – tells about young people who extract the black mountain in the city of Kitta – and record rhythms of life among the residents of the Wusakile neighborhood.

They work in the tombstones of gangs known as “Erabos”, corruption “Boys’ prisons” – hinting at their perceived crime.

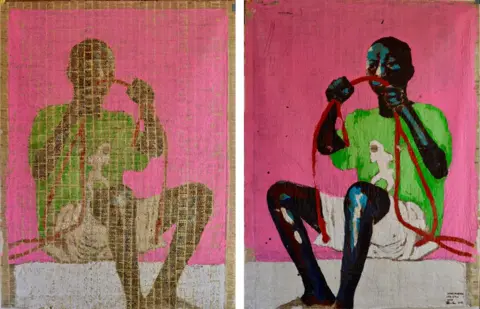

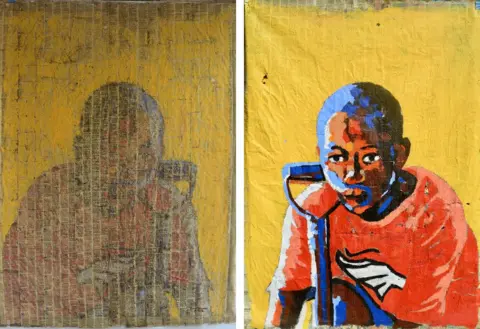

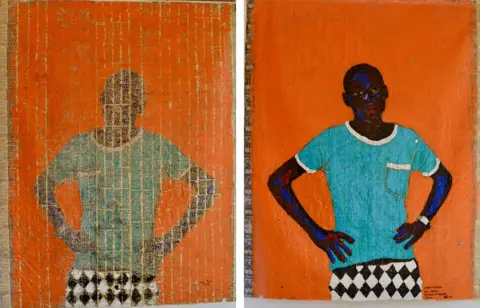

The artist painted a number of large portraits using old newspapers as a canvas. He cut out articles that attract his attention – what he calls “grand stories” – and sticks to them on the substrate.

It uses a gun solder to burn some words and create a number of perforations in stories. Then it pours the paint to create portraits or what it calls “small stories”.

“I take these grand stories, and I create holes so that you can no longer make sense of stories. Then I impose images of the people I know – to show that small stories, small stories of ordinary people are also considered,” – explains Mvab.

“They have important stories and are part of a greater story.”

Old mwab

Old mwabPortraits can be seen on both sides and, in the characteristic style of MWABA, brightly colored.

The works are covered with transparent acrylic and the borders of the newspaper, which is conducted with the transparent tape, because they are very fragile – as the existence of the people who are depicted by MVAB.

They live in the shadow of the black mountain – on the site of the early 1930s of waste full of toxic heavy metals – applying chaos on human health and the environment.

One picture with his current job has a name Erab And shows the miner, which prepares the safety ropes that are connected around his waist when it sinks down on narrow unstable tunnels, dug by hand and are prone to landslides.

Old mwab

Old mwabEarlier this year, all the water supply to the kitvu, which lives about 700,000 people, was closed after a catastrophic waste from a nearby copper mine, owned by Chinese copper, in the flows coming along the neighborhood, as a mustache, in one of the most important waterways, the cafes.

Mwaba hears stories about the hardships and survival during the image workshop, photography and performance that he and other artists have spent several years.

Shoulder A young man who almost hugs his precious “shofolo” – Zambian English, or Zamglish, a word for shovel. Such tools are “personal lifeline,” says MVAB.

Old mwab

Old mwabEdit Player Tuba Local Church Group captures when one morning is held the streets.

Most of the social lives in the mustache rotate around the church, or in the bar, says Mwab.

Old mwab

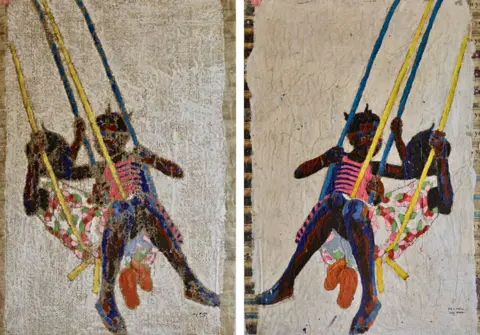

Old mwabBut two young girls in Chilly Make your own entertainment on the home swing.

In durable branches of the yellow and blue heavy-duty cables when the high voltage electric cables were devoid of copper wires and sold in the form of scrap.

Old mwab

Old mwabMvab comes from the miners’ family – his great -grandchildren and one grandfather worked on the mines and his father over the ground.

But the interest of 49 years of age to the impact of Zambia production as a subject for his paintings began almost by accident in 2011, after he helped his daughter Zoe with a scientific project at the Chinese International School in which she attended the Lusaka capital.

The task was to demonstrate how the plants absorb minerals and water. He and Zoya came to the market and bought Chinese cabbage. This is not fundamental, but now they eat in many Zambian houses.

It has a white stem, so it is ideal for the absorption of food dyes that Zoe decided to use to show how minerals would be similar to the plant.

MVAB remembers that the use of Chinese cabbage has made the audience “difficult and so inconvenient”.

Old mwab

Old mwabAt the time, the late Michael Satu was campaigning for the presidency – and the tension was high from its showcase rhetoric against the Chinese, accused at the local level of the dominant in the Zambian economy and the operation of workers.

Thus, MVAB turned the scientific project into an artistic work – in which he studied the presence of the Chinese in the mining sector of the Zambia through three Chinese cabbage leaves, one painted yellow to display copper, one blue for cobalt and the third red for manganese.

His Chinese cabbage brought MWABA a lot of international recognition, and he returned to Zambia in 2015, glowing with the success of art and exhibitions in Germany.

He went to Kitta, where he spent several years of childhood. But his attention has changed only from studying the presence in Zambia to the Chinese to try to tell the story of the people of Black Hill.

“I returned to the place where I grew up and everything has changed so much,” says the artist, adding that “I never imagined that I would see the situation I see now – poverty.”

“It was a very emotional space, and I was sad,” Mwab says.

Old mwab

Old mwabMvab moved to Kasama in the northern province in 1994, after his father suddenly died. Three years later, Zambia’s mines were privatized – which led to massacre losses and an unprecedented economic crisis in the copper field.

Black Mountain – always a source of environmental and health – now it has become a place to make money.

“The worst thing happened when the black mountain was super-graphic, most of these young people threw school.”

Not having the opportunity to get a job, Mvab’s cousin joined the Erasba crew. Every day he wakes up and risks his life to stay afloat and feed his family.

But even if the government banned mining, the riches of the garbage is heavily controlled by the aggressive hierarchy – with the pinnacle, sometimes very rich, the Erabas often corresponds to its nickname.

Disappointment on the chain of herabo – feeling exploited, refuse education to finance someone else’s lush lifestyles, and little in their futures – reflected in the picture of one young man in a turquoise t -shirt, which stands confidently on the hips.

Old mwab

Old mwabBoss on the day He left a workshop in which MVAB invited people to take a picture, striking a posture that reflected their hopes and dreams.

And sometimes the art of Mvaba can change the course of someone’s life.

Mvaba recalls the time when the senior georbo came to the workshop and said, “Hey, I really like what you are doing.

“I think I may not understand it, but it is better for my young brother to come here because I don’t want him to survive what I survived.”

Penni Dale-journalist-freelance, podcast and creator of a documentary based in London

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC