Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

[ad_1]

Reuters

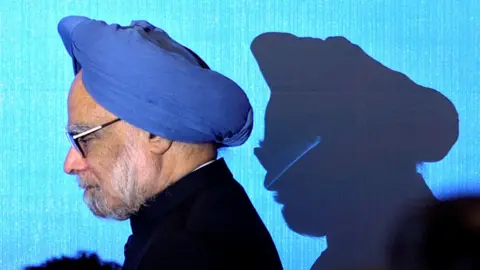

ReutersThe perspective of a shy politician is quite difficult to imagine. Unless that politician is Manmohan Singh.

Since The death of the former Prime Minister of India on Thursday, much has been said about the ‘kind and gentle politician’ who changed the course of Indian history has affected the lives of millions.

His state funeral will take place on Saturday and the Indian government has declared seven days of official mourning.

Despite a distinguished career – he served as India’s central bank governor and federal finance minister before becoming prime minister for two terms – Singh has never come across as a politician on the big stage, lacking the public swagger of many of his peers.

Although he gave interviews and held press conferences, especially during his first term as prime minister, he chose to remain silent even when his government was mired in scandal or when his cabinet faced accusations of corruption.

His gentlemanly demeanor was equally pitied and idolized.

Reuters

ReutersHis supporters said he was cautious don’t pick unnecessary battles or make high promises and that he focused on results – perhaps the best example is pro-market reforms he became the finance minister, which opened India’s economy to the world.

“I don’t think anyone in India believes that Manmohan Singh can do anything wrong or screw things up,” he said. former Congress colleague Kapil Sibal once said,. “He was very cautious and always wanted to be on the right side of the law.”

His opponents, on the contrary, mocked him, saying that he shows some kind of blur, inappropriate politics, not to mention the prime minister of a country with more than a billion people. His voice – hoarse and breathless, almost like a tired whisper – was often the subject of jokes.

But that same voice was also endearing to many who found him relatable in the world of politics, where lofty, high-octane speeches were the norm.

Singh’s image as a media-shy, modest, self-absorbed politician never left him, even as his contemporaries, including members of his own party, went through dramatic cycles of rethinking.

However, it was the dignity with which he maneuvered through every situation – even a difficult one – that made him so memorable.

Born into a poor family in what is now Pakistan, Singh was the first Sikh Prime Minister of India. His personal story – as a Cambridge- and Oxford-educated economist who overcame insurmountable odds to climb the corporate ladder – combined with his image as an honest and thoughtful leader has already made him a hero to India’s middle class.

But in 2005, he surprised everyone when he publicly apologized in Parliament for the 1984 riots that killed around 3,000 Sikhs.

The riots, in which several members of the Congress party were accused, erupted after the assassination of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. One of them later said they shot the Congress politician to avenge a military operation she ordered against separatists holed up in Sikhism’s holiest temple in Amritsar, northern India.

It was a bold move – no other prime minister, including from the Congress party, had gone so far as to apologise. But it healed the Sikh community and politicians from different parties respected him for his courageous act.

Reuters

ReutersA few years later, in 2008, Singh’s low-key leadership style won more praise after he signed a landmark deal with the US that ended India’s decades of nuclear isolation, allowing India access to nuclear technology and fuel for the first time since its tests in 1974.

The deal was widely criticized by opposition leaders and Singh’s allies, who feared it would jeopardize India’s foreign policy. However, Singh managed to save both his government and the deal.

The 2008-2009 period also witnessed global financial turmoil, but Singh’s policies were credited with shielding India from it.

In 2009, he led his party to a resounding victory and returned as prime minister for a second term, cementing his image as a benevolent leader, or rather the fascinating idea that leaders could to be kind.

For many, he became the epitome of virtue, a “reluctant prime minister” who stayed out of the limelight and refused to make any dramatic gestures, but was also unafraid to take bold decisions for the future of his country.

Then everything started to unravel.

A series of corruption allegations – first around the hosting of the Commonwealth Games and then over the illegal distribution of coal deposits – has caused trouble for the Congress party and Singh’s government. Some of these allegations of corruption were later found to be false or exaggerated. Some cases from that period are still pending in the courts.

But Singh was already starting to feel some pressure. During his tenure, he made several attempts at reconciliation with India’s arch-rival Pakistan, hoping to thaw decades of frosty relations.

This approach was sharply questioned in 2008, when a terror As a result of the attack by the Pakistani terrorist group in the city of Mumbai, 171 people died.

60-hour siege, one of the bloodiest in the country’s history opened a chasm of accusations, as the opposition blamed the government’s “soft stance” on terrorism for the tragedy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the years that followed, other decisions taken by Singh backfired.

In 2011, an anti-corruption movement led by social activist Anna Hazare rocked the Singh government. The frail 72-year-old man became an icon for the middle class as he demanded tougher anti-corruption laws in the country.

Singh, being a middle-class hero, was expected to be more perceptive about Hazare’s demands. Instead, the prime minister tried to suppress the movement by allowing the police to arrest Hazare and break up his demonstration.

The move sparked a wave of public and media hostility against him. Those who once admired his understated style wondered if they had mistaken a politician and began to view his quiet demeanor through a less generous lens.

The feeling intensified the following year when Singh refused to comment for more than a week on the horrific gang-rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi.

To make matters worse, India’s economic growth has slowed. Corruption grew and jobs were cut, causing waves of public anger. And Singh’s unassuming nature, which once made his every move seem like a revelation, has been labeled by some as smug, insecure and even arrogant.

However, Singh never tried to defend himself or explain himself and faced criticism calmly.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt was like that until 2014. At a rare press conference, he announced that he would not run for a third term.

But he also tried to set the record straight. “I sincerely believe that history will judge me more kindly than the modern media or, for that matter, the opposition parties in parliament,” he said, listing some of the biggest achievements of his tenure.

He was right.

As it turned out, neither the Congress nor Singh could fully recover from the damage as they lost the general elections to the BJP. But despite many obstacles, Singh’s image as a good and shrewd leader has stayed with him.

Throughout his premiership and despite a second term plagued by controversy, he maintained an aura of personal dignity and integrity.

His policies were seen to be geared around the middle class and the poor – he approved multiple pay rises for central government employees, curbed inflation and introduced iconic schemes on education and jobs.

It may not have been enough to save him from political difficulties or protect him from some setbacks in his career.

But there was something more to his shyness; he was a leader of steely determination.

[ad_2]

Source link