Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Museum of Women’s History Zambia

Museum of Women’s History ZambiaThe wooden hunting tool panel, inscribed by the ancient letter from Zambia, creates waves in social media.

“We have grown, as they say that Africans do not know how to read and write,” says Samba Yong, one of the founders of the Museum of Virtual Women’s History Zambia.

“But we had our own way of writing and transmitting knowledge that were fully laid out and not noticed,” she says the BBC.

It was one of the artifacts that launched an Internet Company to highlight women’s roles in the pre -colonial communities – and reviving cultural heritage that is almost erased with colonialism.

Another intriguing object is a bizarrely decorated leather cloak that is not visible in Zambia for more than 100 years.

“Artifacts mean a story that matters – and a story that is largely unknown,” says Jong.

“Our relations with our cultural heritage were thwarted and obscured by colonial experience.

“It is also shocking how much the role of women was deliberately removed.”

Museum of Women’s History Zambia

Museum of Women’s History ZambiaBut, says Yong, “there is a revival, need and hunger to contact our cultural heritage – and return who we are, whether through fashion, music or academic studies.”

“We had our own language of love, beauty,” she says. “We had ways we took care of our health and the environment. We had well -being, union, respect, intelligence.”

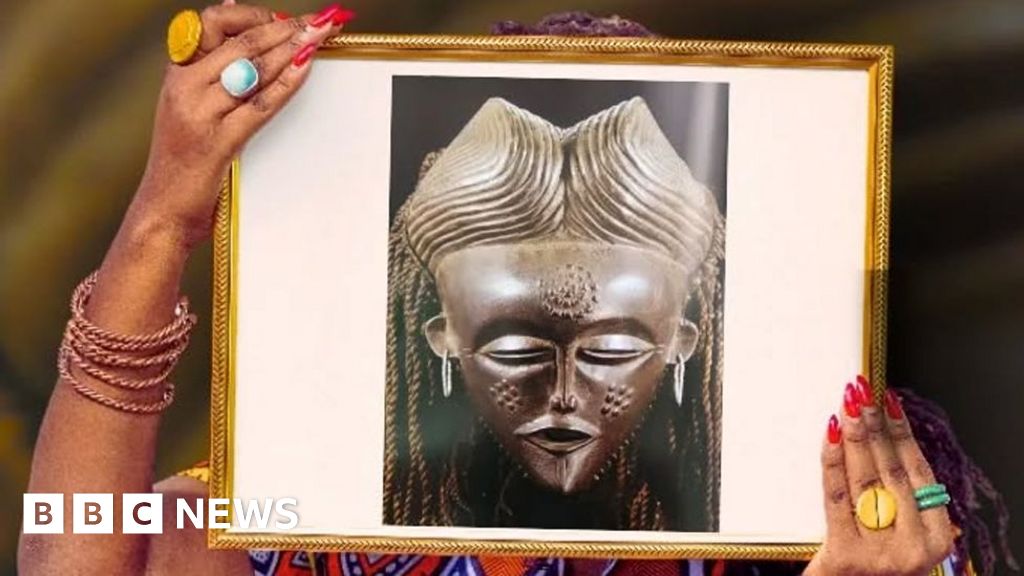

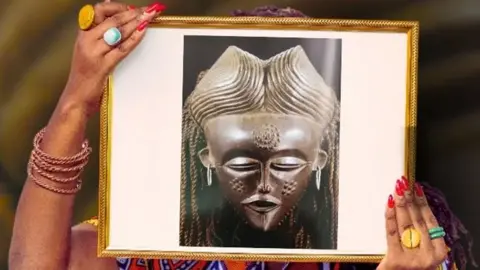

Social networks were located 50 objects – Along with information about their meaning and purpose, which shows that women are often at the heart of society’s beliefs and understanding of the natural world.

Images of objects are presented inside the frame – playing the idea that the volume can affect how you look and perceive the image. Just as British colonialism has distorted Zambian stories – through systematic silence and destruction of local wisdom and practice.

The framework project uses social media to push away from the still striking idea that there are no knowledge systems in African societies.

The facilities were mostly collected in the colonial era and were stored in museums around the world, including Sweden – where the trip to this current social media project began in 2019.

Yonga visited the capital, Stockholm, and a friend offered to meet with Michael Bareth, one of the curators National Museums of World Cultures in Sweden.

She did – and when he asked her from which country she was surprised by Yong, hearing, as he said that there were many Zambian artifacts in the museum.

“It really undermined my mind, so I asked, ‘How in a country that did not have a colonial past in Zambia, there were so many artifacts from Zambia in her collection? “

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Swedish researchers of ethnographers and botany would pay for a trip to British ships in Cape Town, and then made their way deep into the rail and feet.

The museum has about 650 Zambian cultural objects collected over the century – as well as about 300 historical photos.

Museum of Women’s History Zambia

Museum of Women’s History ZambiaWhen the yang and its co -founder of the Mulenga Virtual Museum studied the archives, they were surprised, finding that the Swedish collectors traveled far and wide – some artifacts come from the Zambia districts that are still distant and difficult to reach.

The collection includes fishery baskets with cane, ceremonial masks, pots, shells from the collar – and 20 leather cloaks in the pristine state collected during the 1911-1912 expedition.

They are made of Batwa male leather and wear women or used by women to protect their children from elements.

The sword outside is “geometric patterns, carefully, delicately and beautifully designed,” Jong says.

There are photos of women wearing cloaks, and 300 pages of a notebook, written by a man who brought cloaks to Sweden – ethnographer Eric van Rosen.

He also drew illustrations showing how the cloaks were developed and photographed women who carry the cloaks.

“He took great pain to show the cloak that was developed, all the corners and tools used, and () the geography and location of the region from where it came from.”

The Swedish Museum did not conduct any research on the pockets – and the Council of National Museums Zambia did not even know what existed.

So Yonga and Kapweepwe went to learn more from the Bengwew community in the northeast of the country from where the cloaks came from.

“There’s no memory about it,” Jong says. “Everyone who had this knowledge of the creation of this particular textile – that leather cloak – or realized that there was no stories.

“Thus, it existed only in this frozen time, in this Swedish museum.”

Museum of Women’s History Zambia

Museum of Women’s History ZambiaOne of Yonga’s personal favorites in the frame project is Son or Tuson, ancient, complicated and now rarely used system of writing.

It comes from the people of Chok, Luchazi and the echo that live in the border areas of Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Northwest Region of Jongo Zambia.

Geometric patterns were made in the sand, on the fabric and on the body of people. Or cut into furniture, wooden masks used in masquerade, and a wooden box used to store tools when people hunt.

Samples and symbols carry mathematical principles, cosmos, reports of nature and the environment – as well as instructions on society.

Original custody and teachers Sona were women – and still there are living elders who remember it works.

They are a huge source of knowledge for the constant confirmation of Yonga scientists research such as Marcus Matt and Paul Gerdez.

“Sona was one of the most popular messages on social media – with people who expressed surprise and huge excitement, exclaimed,” How, what? How is this possible? “

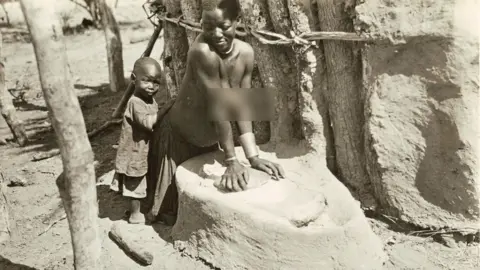

Queen in the Code: Female Power Post characters include a photo of a woman from a tongue community in southern Zambia.

She has hands on a grinding machine, a stone used to grind the grain.

National Museums of World Cultures

National Museums of World CulturesDuring the excursion, researchers from the Zambia Women’s Museum found that the grinding stone was not just a kitchen tool.

He belonged only to the woman who used her – she was not handed over to her daughters. Instead, it was located on her grave as a tombstone from respect for the deposit, which the woman brought into the food security of the community.

“What can only look like a grinding stone is actually a symbol of female power,” Jong says.

In 2016, the Zambia Women’s History Museum was created Document and archive women’s stories and indigenous knowledge.

It conducts research in communities and creates the Internet -Archives of subjects that were taken from Zambia.

“We are trying to collect a puzzle without even having all the works – we are hunting for treasures.”

Hunting for the treasures that changed the life of yongs – so that it hopes that the staffing project in social media will also make for other people.

“Having a sense of my community and understanding the context of who I am historically, politically, socially, emotionally – this has changed the way of interaction in the world.”

Penni Dale-journalist-freelance, podcast and creator of a documentary based in London

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC