Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC NEWS RUSSIAN

BBC

BBCThe dissidents who fled in Alexander Lukashenko’s management in Belarus spoke about the threats against them and their relatives at home.

Hundreds of thousands of Belarusians estimated their country since the brutal repression of widespread opposition protests in 2020, after 70 -year -old Lukashenko declared victory in the presidential election, which was widely convicted as falsified.

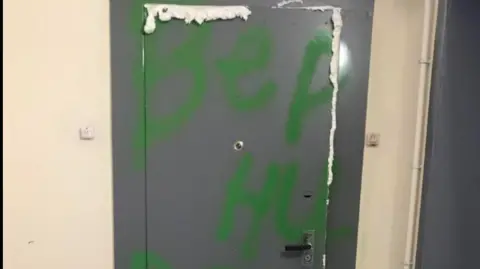

Among the exile was the 26th journalist Tatiana Asurkevich, who continued to write about events in Belarus. Then, earlier this year, she found that the door of her apartment in the Minsk capital was sealed with construction foam.

She immediately guessed who could blame. She decided to resist one of her followers on Instagram, who repeatedly reported it with unwanted compliments and views on the Belarusian opposition movement and journalism in exile.

“If there are criminal cases (against me), just say so,” she said. “I have nothing to do with this apartment – there are other people. Why do you do it?”

The man immediately changed his tone to more official, saying that the criminal cases were not his responsibility, but he could ask the appropriate department.

Then he made a request: can she, in exchange for help, share information about Belarusians who are fighting for Ukraine, especially since she wrote about them before?

Ashurkevich blocked him.

In Belarus itself, tens of thousands of people have been arrested in the last five years for political reasons, Viana’s human rights group reports.

But hundreds of critics of the 31-year rule of Lukashenko also faced persecution abroad.

Lukashenko and Belarusian state media often accuse opposition activists of “treason” and planning a coup through the West. Authorities justify the targeting of activists abroad, claiming that they are trying to harm national security and overthrow the government.

Several people who spoke to the BBC received messages and telephone calls, sometimes seemingly harmless, sometimes with thinly veiled threats – or promises catch.

55 -year -old Anna Krasulin takes them so often that she used to put her phone in the flight mode before you go to bed.

“I see who is handing me – a few people. Maybe it’s the same thing using different accounts,” she says.

She is convinced that the authorities are behind it. Ms Krasulin works as a press -secretary of Svetlana Tikhonovskaya, a leader of the opposition, whom many believed that they won in the 2020 elections, which are now in exile.

Both women were convicted in Belarus to 11 and 15 years, respectively, in court trials. The allegations included the preparation of the coup and management of the extremist organization.

Gets the image

Gets the imageSince such lawsuits against political opponents were possible by Lukashenka’s decree in 2022, more than 200 cases were opened last year.

This allows the authorities to raid the accused’s homes and pursue their relatives.

Critics are identified in photos and videos taken at opposition meetings abroad.

Now many have stopped participating in them, fearing their loved ones who remain in Belarus, says Ms Krasulin.

Several people who spoke to report their relatives visiting the authorities.

“It’s awful if you can’t help them. You can’t go back. You can’t support them,” one says.

No one will record or even disclose the details anonymously because of the concerns that their families can suffer.

Their fears are not unfounded. The 39-year-old Artem Swanka, who worked in the real estate, is serving a term of imprisonment of three and a half years for “financing extremism”.

He never talked in public, but his father was an opposition politician who lived in exile.

By breaking the ties between Belarus who escaped, and those left behind are a deliberate strategy of Lukashenka’s government, says journalist and analyst Hanna Lubakov, also convicted in the factory up to 10 years in prison.

“Even if anyone understands everything in Belarus, they will think three times before talking to a” terrorist “,” she says, referring to the list of “extremists and terrorists”, which the authorities inhabit the names of their critics.

Andrei Strytshak

Andrei StrytshakThe BBC sent a request for a comment from the Belarusian Ministry of Internal Affairs, but did not receive a response until the publication.

Some of Libakov’s own relatives also received visits from security services, she says, and the property registered in her name was confiscated.

Everyone with whom the BBC said they believe that the Belarusian authorities seek maximum pressure on those who left to crush all the opposition wherever it is.

Anna Libakova believes that the persecution of dissidents stems from Lukashenko’s personal revenge for the 2020 protests: “He wants us to feel not dangerous abroad to know what we are being watched.”

One of the countries that turned out to be especially dangerous for the Belarusian is Russia. According to the authorities in Minsk, only in 2022 Russia extradited 16 people accused of “extremist crimes”, which is usually related to Lukashenko’s critics.

“The methods used by the Belarusian security forces are very similar to the characteristics of the Soviet KGB, just updated with modern technologies, says Andrei Strytshak, head of the BYSOL group, which supports Belarusian activists.

Threatening messages or promises of reward for cooperation may not work at all, he added. But by throwing a wide network, the authorities can get few who agree to share useful information.

Strytshak calls the regime’s efforts to hunt dissidents abroad a “war for disappearance”, which leaves many activists exhausted and wanting to continue their lives.

“We are doing our best to stay sustainable,” he says, “but every year it takes more and more effort.”