Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC

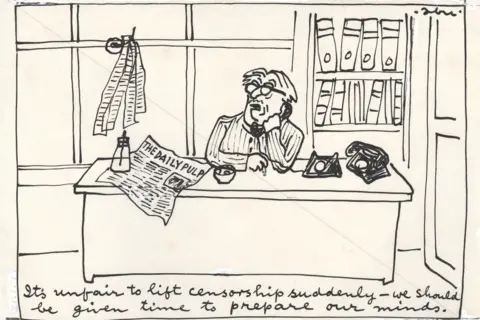

BBC“It is unfair to raise the censorship suddenly,” the editor of the newspaper, who read in the phone, a copy of the daily pulp, dispensed with the table. “We need to give time to prepare our mind.”

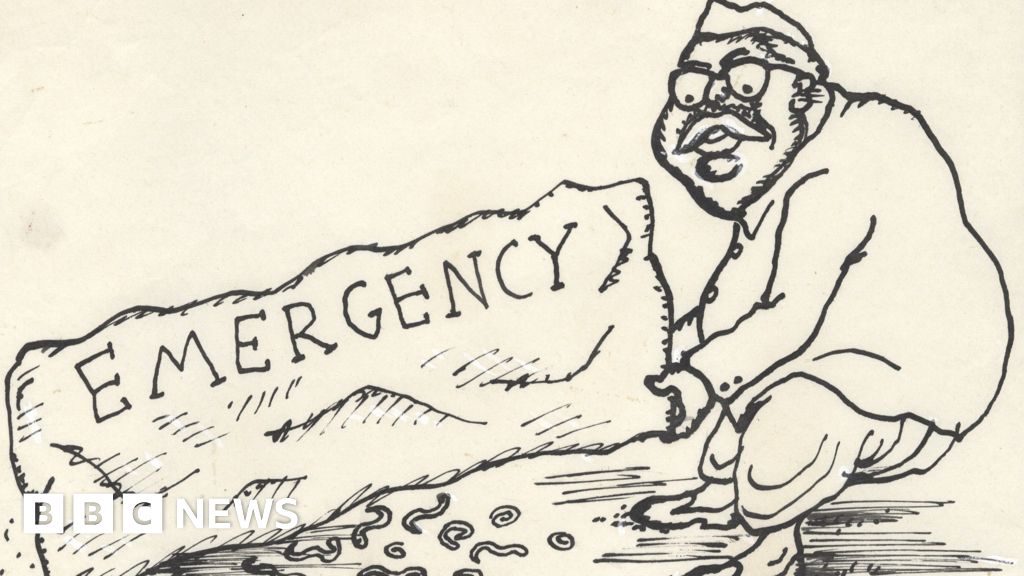

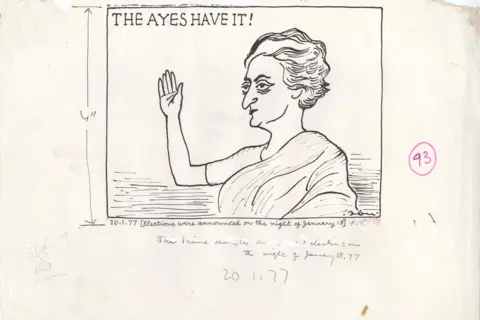

The cartoon that fixes this moment – a shrill and satirical – is the work of Abraham, one of the best political cartoons of India. His handle rolled out power with elegance and edge, especially during 1975 Emergency Situations21-month plot of suspended civil liberties and intricate media under Indira Gandhi.

The press was silenced over the night of June 25. Delhi’s newspaper presses the lost power, and the morning censorship was the law. The government demanded the bend of the press to its will – and as the opposition leader LK Advan, he knows, noted that many “decided to crawl”.

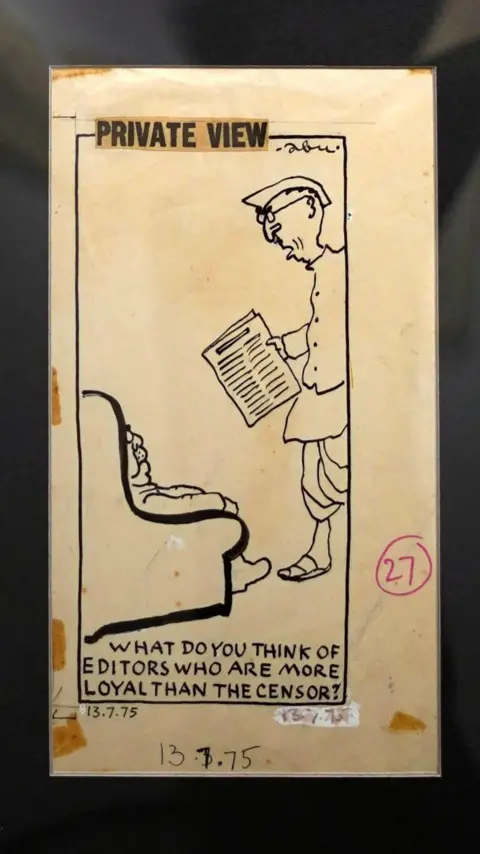

Another famous cartoon – he signed them Abu, after the name of the pen – hence now he shows that a person asks another: “What do you think about editors who are more committed than censorship?”

In many ways, half a century later, the cartoons are still ringing.

Currently India takes attention 151 -y in the Freedom IndexCompiled annually to journalists without borders. This reflects growing trouble Narendra Modi Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the government’s independence. Critics claim that they increase the pressure and attacks on journalists, agree to the media and the contractual place for dissenters. The government rejects these claims, insisting that the media remain free and alive.

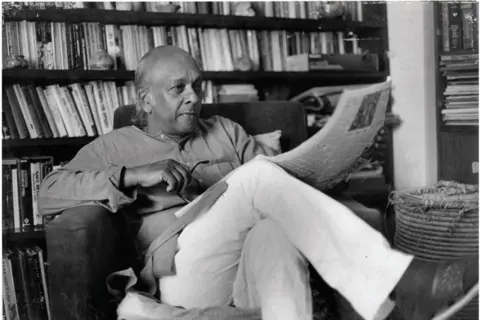

After almost 15 years, drawing cartoons in London for observer and The Guardian, Abu returned to India in the late 1960s. He joined the Indian expression newspaper as a political cartoon at a time when the country fought with intense political shocks.

He later wrote that the design – which required the newspapers and magazines to present their news, editorial articles and even ads to the state censors before the publication – began two days after the announcement of the emergency, were removed a few weeks and then returned a year later.

“I had no official intervention in the rest of the time. I did not interfere with why I was allowed to continue freely. And I’m not interested in finding out.”

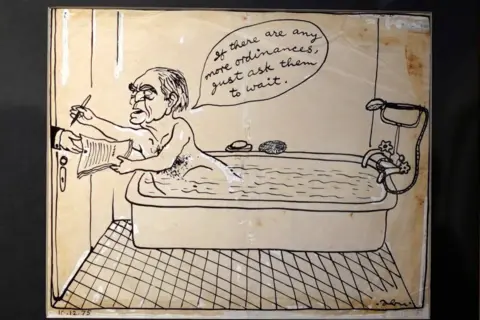

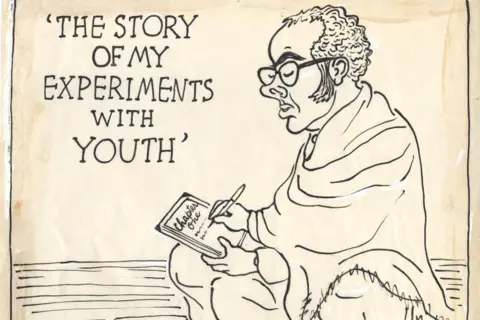

Many of the ABA ambulance cartoons are iconic. One shows that President Fahruddin Ali Ahmed signed the announcement with his bathroom, seizing the haste and accident with which she was issued (Ahmed signed an emergency statement that Gandhi issued shortly before north June 25).

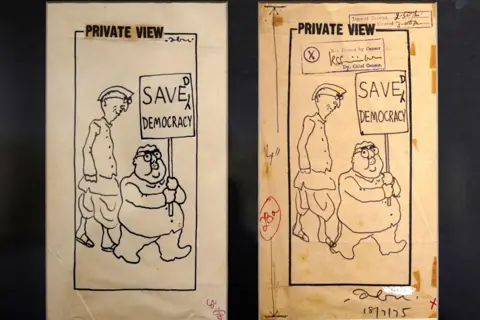

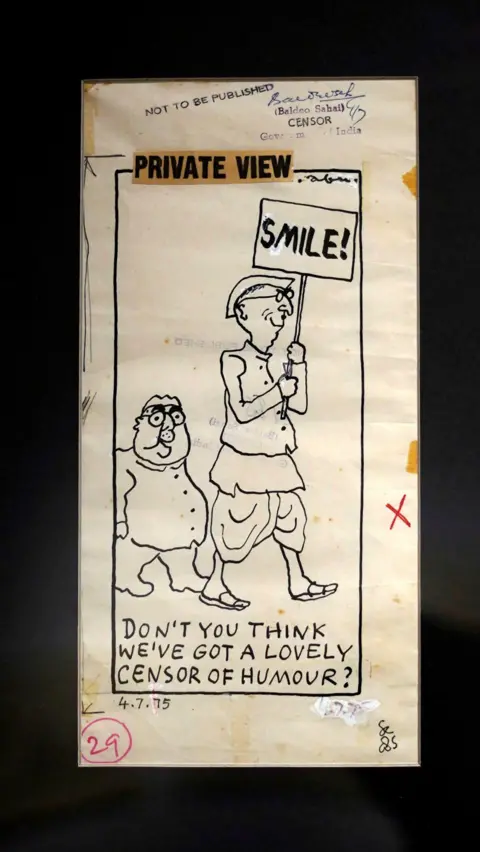

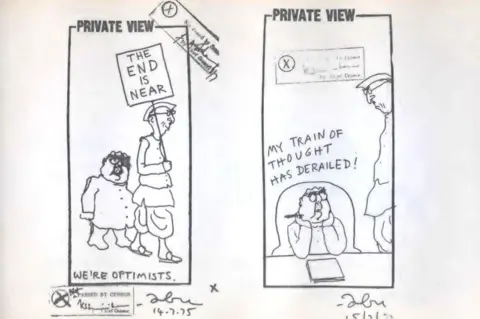

Among the bright works of Abu are a few cartoons, boldly stamped with “Do not transfer censors”, a vivid honor.

In one man holds a poster that proclaims “Smile!” – a tricky blow to the forced potential campaigns of the government during emergencies. His Dedpans satellite: “Do you not think that we have a great censorship of humor?” – a line that is cut to the heart of the solemn impression.

Another seemingly harmless cartoon shows a man at the table, sighing, “My train thought.” Another presented by a protesting sign that proclaims “saved democracy” – “D”, awkwardly added from above, as if democracy itself was thought.

Abu also aimed at Sanji Gandhi, the underage son of Indira Gandhi, who many believed that during an emergency, the government ruled the shadow, possessing a clumsy force behind the scenes. Sanji’s influence was contradictory and afraid. He died in a plane crash in 1980 – four years before his mother was killed by her guards.

Abu work was intensively political. “I came to the conclusion that there is nothing political in the world. Political is just controversial, and everything in the world is controversial,” he wrote in Seminar in 1976.

It also weakened the state of humor – tense and made – when the press was tightened.

“If cheap humor could be produced at the factory, the public would hurry to stand in our range all day. As our newspapers become gradually dim, a reader who is a drowning man, paws in each joke. Either they played.

In the “tongue -in -cheek” column for Sunday standard in 1977, Abu was entertained by the culture of political flattery with a fictional considering the meeting “All Indian Socaphantic Society”.

The fake presents the imaginary president of the society, which announced: “The real sycophanto is non -political.”

The satirical monologue continued to make fun of the proclamation: “Sicophalation has a long and historical tradition in our country …” Friendly ” – our motto.”

The parody of Abu ended with the governing vision of society: “Touching all the available legs and promoting a wide vengeance program.”

Abu, who was born as a etipurat Matthew Abraham in the southern state of Kerala in 1924, began his career as a reporter in a nationalist bombing chronicle, which had less ideology than the fascination with the power of the printed word.

The years of his reporting coincided with the dramatic journey of India to independence, observing the euphoria that covered Bombay (now Mumbai). Reflecting on the press, he later noted: “The press has claims to be a Crusader, but most often seizing the status of -Kwa.”

Two years later, with a weekly, a famous Satirin magazine, Shankar aimed at Europe. A random meeting with British cartoon Fred Jose in 1953 led him to London, where he quickly made a mark.

His debut cartoon was accepted by Punch during the week after his arrival, receiving the praise of the editor Malcolm Maggij as “Magic”.

For two years, the freelance on the competition of London, the political cartoon Abu began to appear in the podium and soon attracted the attention of observer editor David Astar.

Astor offered him the position of staff with the newspaper.

“You are not hard as other cartoons, and your work I was looking for,” he said.

In 1956, at the proposal of Astor, Abraham accepted the name of the pen “Abu”, writing later: “He explained that any Abraham in Europe would be taken as a Jew, and my cartoons will take over for no reason, and I was not even Jewish.”

Astor also assured him in his creative freedom: “You are never asked to draw a political cartoon, expressing ideas that you do not personally sympathize.”

Abu worked for an observer for 10 years, after which three years in The Guardian before returning to India at the end of the 1960s. He later wrote that he was “sad” from British politics.

In addition to the cartoon, Abu served as an allocated member of the House of Parliament of India from 1972 to 1978. In 1981, it launched salt and pepper, a comic book that has been going on for almost two decades, combining gentle satire with everyday observations. He returned to Kerala in 1988 and continued to draw and write to death in 2002.

But the heritage of Abu was never just about the punch – it was about deeper truths that his humor revealed.

As he once noticed, “if anyone noticed a decrease in laughter, the reason may not be the fear of laughing, but the feeling that reality and fantasy, tragedy and comedy have everything, somehow confused.”

This blurring of absurdity and truth often gave its work its advantage.

“Award for the joke of the year,” he wrote during an emergency, “must go to the reporter of the Indian news agency in London, who approved the British newspaper comments on India within the framework of emergency situations that” trains work on time ” – not realizing that it was a standard English joke. Humorous Humanists. “

Cartoons and photos of Abu, courtesy Aishi and Janaki Abraham