Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

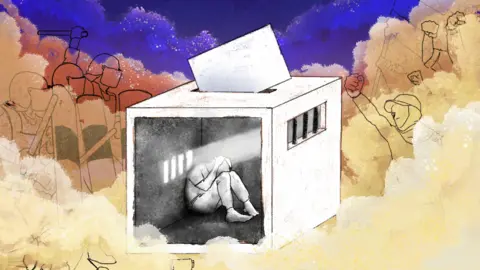

Daniel Arce-Lopez / BBC

Daniel Arce-Lopez / BBC“I have already been tortured and repressed, but they will not remain silent. My voice is the only thing I have left.”

This is how Juan, a young man in his 20s, begins his story. He claims that he was subjected to physical and psychological torture by Venezuelan security forces after his detention in connection with the July 28 presidential election.

He was one of many hundreds of people arrested during the protests after electoral authorities – dominated by government loyalists – declared incumbent President Nicolas Maduro victorious.

The National Electoral Council (CNE) did not release the results of the vote, and the Venezuelan opposition described the official results as fake, noting that the results of the vote it received with the help of election observers showed a landslide victory for its candidate, Edmundo Gonzalez.

Juan was released from prison in mid-November, days after Maduro called on judicial authorities to “correct” any injustice in the arrests.

The BBC spoke to him via video link. For his own safety, we have decided to withhold some details of his case and have changed his name.

The young man claims that many of the detainees are treated harshly, given “rotten food”, and the most recalcitrant are locked up in “torture cells”.

He showed the BBC documents and evidence that corroborated his story, which coincided with other testimonies and with complaints from non-governmental organizations.

Reuters

ReutersJuan, an anti-government political activist, says the election campaign and the days leading up to the election were “marked with hope” and many people were eager to vote for change.

But the announcement of Maduro’s victory shortly after midnight that Sunday turned what had been a celebratory mood for many into confusion and anger.

Thousands of Venezuelans took to the streets to protest the result, which they called fake.

The opposition and international organizations say that there was a police crackdown that resulted in the deaths of more than 20 protesters.

Maduro and some of his officials, in turn, blamed the death on the opposition, “extreme right” and “terrorist” groups.

Gonzalo Himiob of the Venezuelan NGO Foro Penal says people have been arrested just for “celebrating the opposition’s announcement of Edmund Gonzalez as the winner or for posting something on social media.”

“We also have cases when people did not even protest, but for some reason were close to the protest and were arrested,” he added.

Juan says this is what happened to him.

Daniel Arce-Lopez / BBC

Daniel Arce-Lopez / BBCThe youth politician says he was on an errand when a group of men in hoods intercepted him, covered his face and beat him, accusing him of being a terrorist.

“They doused me with bottles of incendiary mixture and gasoline, and then they took me to the detention center,” he continued.

He was held in a prison in the interior of Venezuela for several weeks before being transferred to Tocarón, a notorious maximum security prison located about 140 km southwest of the capital, Caracas.

There he had what he describes as the worst experience of his life.

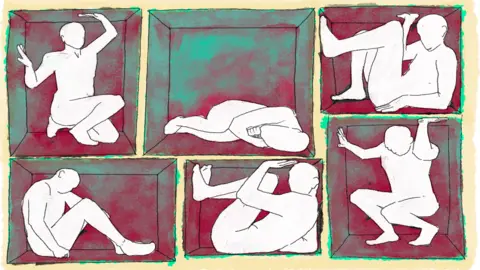

“When we arrived in Tokaron, we were stripped, beaten and insulted. We were forbidden to raise our heads and look at the guards; we had to lower our heads to the floor,” says Juan.

Juan was assigned a small cell measuring three by three meters, which he had to share with five other people.

There were six sleeping places on three bunks, and in one corner there was a septic tank and “a pipe that served as a shower.” It was a bathroom.

“In Tacoron, I felt more like a concentration camp than a prison,” says the young man. He describes the beds as “concrete tombs” with very thin mattresses.

“They tortured us physically and psychologically. They didn’t let us sleep, they kept coming to ask us to get up and line up,” he explains.

“We woke up around 5:00 a.m. to line up behind the camera. The guards asked to show the passes and numbers.”

He adds that around 06:00 the water was turned on for six minutes so that they could bathe.

“Six minutes for six people and only one shower with very cold water. If you were the last one and didn’t get the soap off, you were stuck in the soap for the rest of the day,” he says.

Then, he adds, they waited for breakfast, which came sometimes at 6 o’clock, then at 12 o’clock.

Dinner is sometimes at 9:00 p.m., then at 2:00 a.m.

“There was nothing else to do but wait for food. We could only walk around the small cell and tell stories. We also talked about politics, but quietly, because if the guards heard us, they would punish us. “

Juan says many of his cellmates were depressed and acting like zombies.

“They gave us rotten food – leftover meat that you give to chickens, dogs, or sardines that have expired.”

Some detainees were routinely beaten or made to “walk like frogs” with hands on their ankles, he says.

He describes the “lockdowns” where those deemed most rebellious, or those who dared to speak about politics or ask to call relatives, were sent.

Juan says that he was in one of the penitentiaries in Tacoron and that he only received food once every two days.

“It’s a very dark chamber, one meter by one meter. I was very hungry. I was kept thinking about all the injustice that was happening and that one day I would get out of there,” he says.

Another torture chamber is known as “Adolphe’s bed,” Juan says, named after the first person to die there.

“It’s a dark, oxygen-deprived room the size of a vault. They put you in there for a few minutes until you can’t breathe, pass out, or start banging on the door in desperation. They put me in there and I went on for a little over five minutes I thought I was going to die,” he recalls.

Daniel Arce-Lopez / BBC

Daniel Arce-Lopez / BBCA young man says that in this prison, inmates have 10 minutes to exercise outside three times a week, but many just sit in their cells.

Gonzalo Himiob of Foro Penal describes conditions in Tokarona as “horrendous” and says detainees’ basic rights, such as access to a lawyer of their choice, are being violated.

“Everyone has public defenders — the government knows that if it allows access to a private attorney who is not a public official, he or she can document all the due process violations that occur.”

In October, United Nations (UN) experts reported serious human rights violations committed in the run-up to the presidential election and during the protests that followed, including political persecution, excessive use of force, enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions by state security forces and related civic groups.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is currently investigating the Venezuelan government for possible crimes against humanity.

The Venezuelan government denies the allegations and says that the investigation “responds to the intention to use the mechanisms of international criminal justice for political purposes.”

The BBC has requested an interview with the prosecutor’s office about claims of ill-treatment and torture of detainees, but had not received a response by the time of publication.

Getty Images

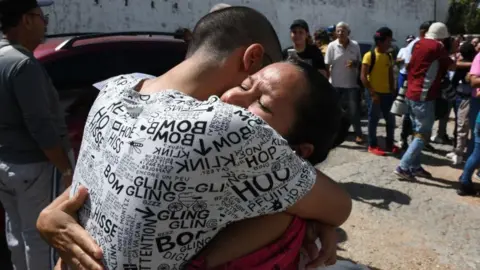

Getty ImagesJuan was released in November, but according to the Foro Penal, as of December 30, 1,794 political prisoners remained in Venezuela.

According to Juan, many of those detained in Tacoron pin their hopes on one date: the inauguration of the president on January 10, 2025.

On this day, opposition candidate Edmundo Gonzalez, who lives in exile in Spain, announced that he would return to Venezuela and take over the presidency.

He bases his claims to the position of president on official vote counts, which the opposition managed to collect with the help of observers.

Those results, which account for 85% of the total, have been uploaded to a website and reviewed by independent observers who say they indicate a landslide victory for Gonzalez.

On Tuesday, US President Joe Biden met with Gonzalez and called him the “real winner” of the elections in Venezuela.

However, it is unclear how Gonzalez, for whom authorities have issued an arrest warrant, plans to enter Venezuela or who will swear him in, given that the National Assembly is dominated by Maduro supporters.

However, Juan says that the prisoners in Tacoron are hopeful that there will be a change of government on Friday and their release from prison.

Meanwhile, Maduro’s government has called any talk of a political transition a “conspiracy” and threatened that anyone who supports a change in leadership will “pay for it.”

Juan admits he feels a certain guilt about being free when hundreds of his “comrades are still suffering” in prison.

But he says he is determined to return to the streets to show his support for Edmund Gonzalez on January 10.

“I am no longer afraid of the Venezuelan government,” he explains.

“They have already accused me of the worst crimes, such as terrorism, even though I am just a young man who has done nothing more than love his country and help those around him.”

“I’m not afraid,” Juan repeats, before admitting that he left the written statement in a safe place “in case something happens to me.”

Illustrations by Daniel Arce-Lopez.