Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC NEWS

Pritam Roy/BBC

Pritam Roy/BBCSean Banu still shuddered when he thinks about the last few days.

A 58-year-old resident of the Barpeth district in the northeast state of India, says that she was summoned to a local police department on May 25 and then taken to the border with neighboring Bangladesh. From there, she said, she and about 13 other people were forced to go to Bangladesh.

She says she was not told why. But it was a scenario she was afraid – Ms Bana said she has lived in Asom all her life, but for the last few years she is desperately trying to prove that she is an India citizen, not an “illegal immigrant” from Bangladesh.

“They pushed me under shot. After these two days on the ground, no one – between India and Bangladesh, says she went to the old prison on Bangladesh.

Two days later, she and a few others – she was not sure whether they were all from one group sent with her – accompanied by Bangladesh officials across the border, where Indian officials allegedly met and sent home.

It is unclear why Mrs. Banu was abruptly sent to Bangladesh and then returned. But her case is in a number of recent cases where in the past, the officials in ASAMA gathered people who announced foreigners on the tribunals – on suspicion that they “illegal Banglades” – and sent them across the border. The BBC revealed at least six cases where people said their family members were taken away, taken to border cities and simply “pushed”.

Officials from the India border security, the ASAM police and the state government did not answer BBC questions.

The repression of allegedly illegal immigrants from Bangladesh are not new in India – countries are divided into 4.096 km (2545 miles), which can make it relatively easy, although many sensitive areas are strongly protected.

But it is still rare, lawyers who work on these affairs say that people are sharply picking up from their homes and forcing another country without the proper process. These efforts seem to have intensified over the past few weeks.

Adah Sgagria Nazim/BBC

Adah Sgagria Nazim/BBCThe Indian government has not officially stated how many people were sent to the last exercises. But the main sources in the Bangladesh administration claim that India has “illegally pushed out” more than 1,200 people into the country only in May not only from Aama but also from other states. From this, they stated that provided Bangladesh’s anonymity identified 100 people as Indian citizens and sent them back.

In his statement, the Bangladesh border guard stated that patrolling along the border is increasing to restrain these attempts.

India did not comment on these allegations.

While media reports show that recent repressions include Muslim Rokhingy, who live in other states, the situation is especially tense and complex in the ASAM, where issues of citizenship and ethnic identity have long prevalent in politics.

A state that divides nearly 300 km of the border from Muslim, Bangladesh, saw the waves of migration from the neighboring country when people moved in search of opportunities or escaped with religious persecution.

This caused the anxiety of the association people, many of whom are afraid that it brings demographic changes and taking resources from the locals.

Bharatiya Jonatia – in power in ASAM and the national level – has repeatedly promised to stop the problem of illegal immigration, which has been done by the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in recent years.

The register is a list of people who can prove that they came to ASAM by March 24, 1971, the day before neighboring Bangladesh declared independence from Pakistan. There were several iterations on this list, and people whose names did not have, giving the chance to prove their citizenship of India, showing official documents on a quasi-warding forum called Tribunals foreigners.

After the chaotic process, the final project, published in 2019, excluded nearly two million Aama residents – many of them were put in prison camp and others went to the highest courts against their exceptions.

Adah Sgagria Nazim/BBC

Adah Sgagria Nazim/BBCMs Bana said her case was in the Supreme Court, but the authorities were still forced to leave.

The BBC heard similar stories at least six others in ASAM – all the Muslims who say that their family members were sent to Bangladesh at the same time as Ms Banu, despite the necessary documents and live in India for generations. At least four of them returned home, unanswered why they were taken away.

A third of 32 million residents of ASAM are Muslims, and many are descendants of immigrants who have settled there during British domination.

Malek Khatun, 67-year-old Barpeth ASAM, who is still in Bangladesh, says that the local family has temporarily gave shelter.

“I have no one here,” she complains. Her family managed to talk to her, but I don’t know when she can go back. She lost the case in the foreigners’ tribunal and did not go to the Supreme Court to the Supreme Court.

A few days after the recent round of the promotion began, the chief minister of Sarma led the direction of the Supreme Court in February who ordered the government to start work on deportation for people who were “announced by foreigners” but were still held in the detention center.

“People who proclaim foreigners but did not even go to the court, we push them back,” Sarma said. He also claimed that the people who are in court were not “worried”.

But Abwur Razak Bhuyan, a lawyer working on many cases of citizenship in ASAM, claimed that in many recent cases the proper process – which, among other things, will require India and Bangladesh to cooperate in this action.

“What is happening is a deliberate and deliberate misinterpretation of the court’s ruling,” he said.

Recently, Mr. Bhuyan filed a motion on behalf of a student organization seeking the intervention of the Supreme Court, stopping the fact that, according to them, he was a “strong and illegal deflection policy”, but he was asked for the first time to approach the Supreme Court.

Aamir Peerzada / BBC

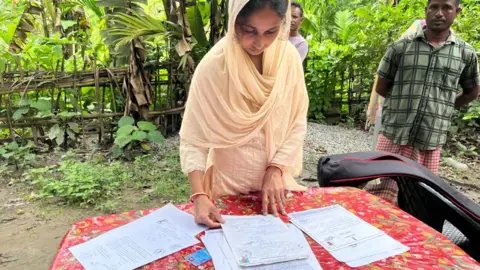

Aamir Peerzada / BBCIn Morigaone, about 167 km from Barpets, Rita Khatun was sitting at a table with a bunch of papers.

Her husband Khairul Islam, a 51-year-old school teacher, was in the same group as Mrs. Banu, who was allegedly seized by the authorities.

The tribunal announced it to foreigners in 2016, after which he spent two years in the remand prison. Like Ms Banu, his case is also considered in the Supreme Court.

“Every document is proof that my husband is Indian,” said Ms. Khatun, overcoming that, she said, there was a certificate of graduation from Mr. Islam and some land recordings. “But this was not enough to prove their nationality.”

He says her husband, his father and his grandfather were born in India.

But on May 23, she says that the police arrived at their home and took Mr. Islam without explanation.

Only a few days later – when a viral video appeared in Bangladesh journalists who interviewed Mr. Islam in the land “None” – the family learned where it was.

Like Ms Banu, Mr. Islam is now sent back to India.

While his family confirmed his return, the police told the BBC that they had no “information” about his arrival.

Sanjim Begum says that her father was proclaimed a foreigner from the case of erroneous identity -he was also accepted on the same night as Mr. Islam.

“My parents call Abdul Latif, my grandfather was Abdul Subhan. The notice came (years ago, from the tribunal foreigners), said Abdul Latif, Schuro Ali. This is not my grandfather, I don’t even know him,” said Ms. Begum, adding that she had all the necessary documents.

Now the family heard that Mr. Latif returned to Asam, but has not yet reached home.

While some of these people returned home, they are afraid that they can be taken again.

“We don’t play,” said Ms. Begum.

“These are the people you can’t throw them on the whim.”

Additional report by AAIMI PARTS and Patter Roy