Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to declare a national emergency as soon as he takes office on Monday, months after promising voters to halve electricity and gasoline prices in the first year of his administration.

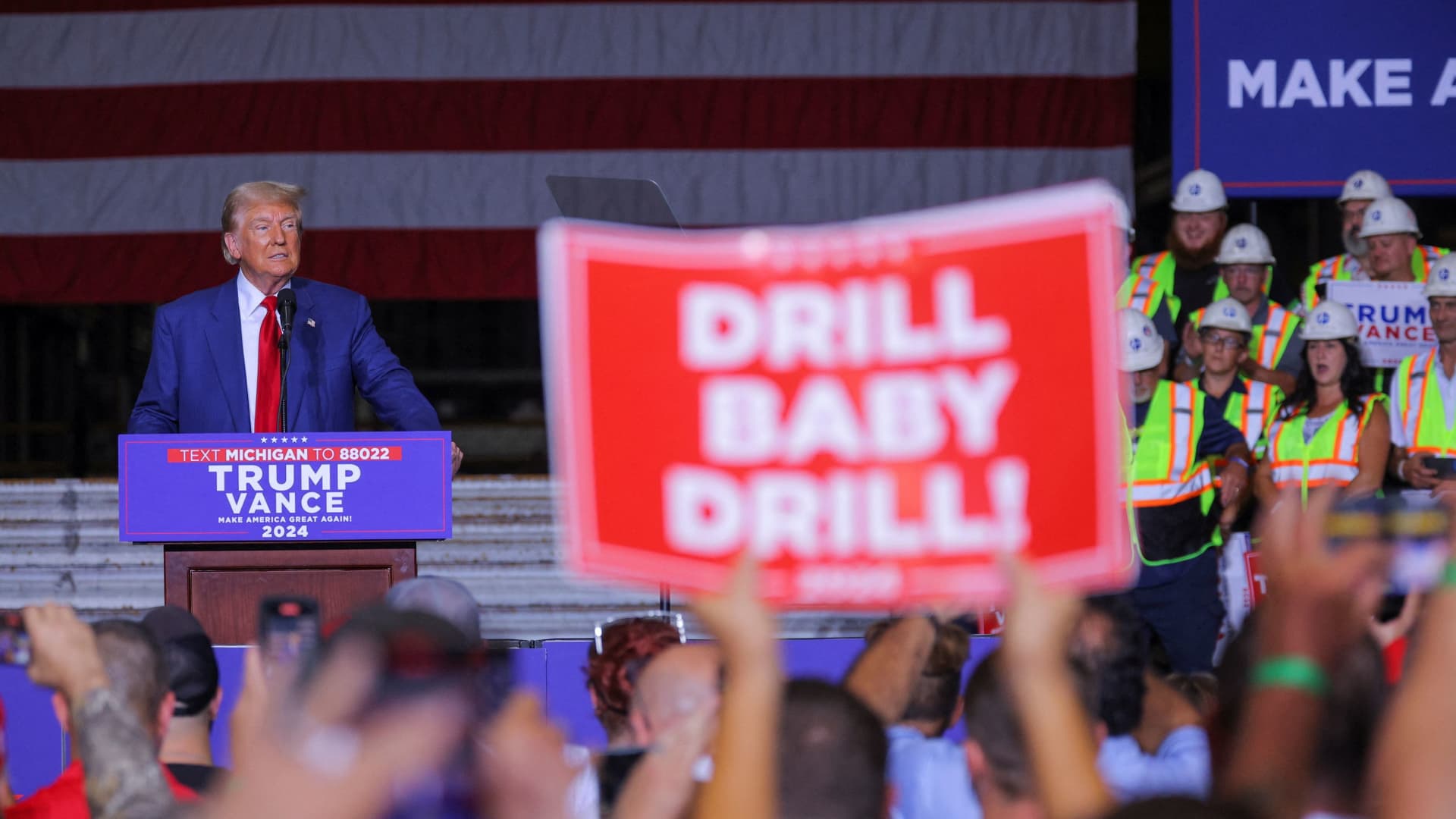

“To achieve this rapid reduction in energy costs, I will declare a national emergency to allow us to dramatically increase energy production, generation and supply,” Trump said. – supporters said at the rally in Potterville, Michigan last August. “From day one, I will approve new drilling, new pipelines, new refineries, new power plants, new reactors, and we will cut red tape.”

Recently, on December 22, the president-elect reiterated his intention “declare a state of emergency in the energy sector” on his first day in office. He promised to issue a series of executive orders to reverse the Biden administration’s policies on natural gas exports, drilling and emissions standards.

Trump plans to create a National Energy Council led by North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgham, his handpicked head of the Department of the Interior. Burgum said during a Senate nomination hearing this week that he expects the board to be created under the executive order.

It is unclear whether the emergency declaration will be largely symbolic or will invoke broader powers beyond the energy executive orders Trump is expected to issue on Monday. The president-elect’s transition team did not respond to a request for comment.

“I think it’s going to be a rhetorical statement about an energy emergency,” said Mike Sommers, president of the American Petroleum Institute, an oil industry lobbying group. “When you put the executive orders together, it’s going to be the answer to what to do with the energy emergency.”

Glen Schwartz, director of energy policy at Rapidan Energy, a consulting firm, said Trump could implement several emergency energy-related laws. Emergencies are often defined by federal law, giving the president broad discretion to use them, Schwartz said.

Schwartz said Trump likely won’t face the courts because they don’t want to challenge presidential decisions related to national security.

“What you end up with is that even if Trump were to expand his emergency powers in an unprecedented way, it’s not clear that the courts would step in to stop any of these consequential actions,” the analyst said.

Schwartz told clients in a research note published last Thursday. Authorities exercising such powers would waive certain energy-related environmental and pollution regulations.

Trump could exempt the fuel under the Clean Air Act to allow gasoline that would otherwise violate federal air quality standards to go on the market, the analyst said. Presidents have often used such waivers whenever they needed to increase the nation’s gasoline supply and keep prices under control, he said.

Trump could also refer to Federal Power Act order power plants to operate at maximum capacity and not meet pollution limits, Schwartz said. The Secretary of Energy can invoke the act in wartime or when a sudden increase in demand or shortage of electricity creates an emergency.

The provision was rarely used after World War II and was mostly reserved for situations where extreme weather overwhelmed power plants, Schwartz said.

The largest network operator in the United States PJM Interconnection warned about a lack of power as coal plants are shutting down faster than new capacity is being added. PJM operates a network in all or parts of 13 states, the Mid-Atlantic, the Midwest and the South.

The situation could become more acute as demand for electricity increases significantly as the technology sector builds energy-intensive data centers to support AI applications.

The first Trump administration considered a law in 2018 to require utilities to buy two years of power from coal and nuclear plants that were in danger of closing. The administration at the time ultimately abandoned the idea after facing pushback from industry.

Trump can also choose a a broader statute which allows the president to suspend pollution laws for industrial facilities, power plants, oil refineries, steel plants, chemical plants and other industrial facilities in emergency situations, Schwartz said.

Federal law is less supportive of the president in forcing new production, Schwartz said. Trump could order federal agencies to speed up environmental reviews of energy projects he supports, such as pipelines, but the president can’t use emergency authority to bypass core environmental policies like the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act, an analyst said.

Oil industry lobbyists at the American Petroleum Institute expect Trump to issue a series of energy-related orders as early as Monday.

The administration is expected to issue an order lifting the pause on Biden’s team new export of liquefied natural gas facilities, Somers said. The president-elect is also likely to try to reverse President Biden’s recent decision to ban drilling in 625 million acres of federal waters. Trump’s authority to do so is contested, and such an order would likely end up in court.

“We believe he has an opportunity to reverse this and we will defend it in court,” Somers said.

The industry expects the president to also order the Interior Department to increase sales of oil and gas leases in the Gulf of Mexico, Somers said. The Biden administration issued the lowest number of rentals in history within the framework of the program designed for 2029.

These decisions are not expected to have an immediate impact on production. The US has been the world’s largest producer of oil and gas for six years, ahead of Saudi Arabia and Russia. General directors of the company Exxon and Chevron made it clear that manufacturing decisions are based on market conditions and not in response to who is in the White House.

“You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink,” Schwartz said. “He can give them all the resources they need to drill, but I haven’t seen anything that suggests he can get them to get it out of the ground.”

Trump is expected to withdraw the US from the Paris climate agreement. Executive orders on tailpipe emissions and fuel economy standards for vehicles are also expected.

Still, only so much can be done with an executive order, Somers said, and directives often have to go through a time-consuming rulemaking process. He said the oil industry is more focused on making more lasting policy changes in the Republican-controlled Congress.

“On day one, they won’t be able to do much other than direct federal agencies to fulfill their promise to dominate energy,” Somers said.