Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

[ad_1]

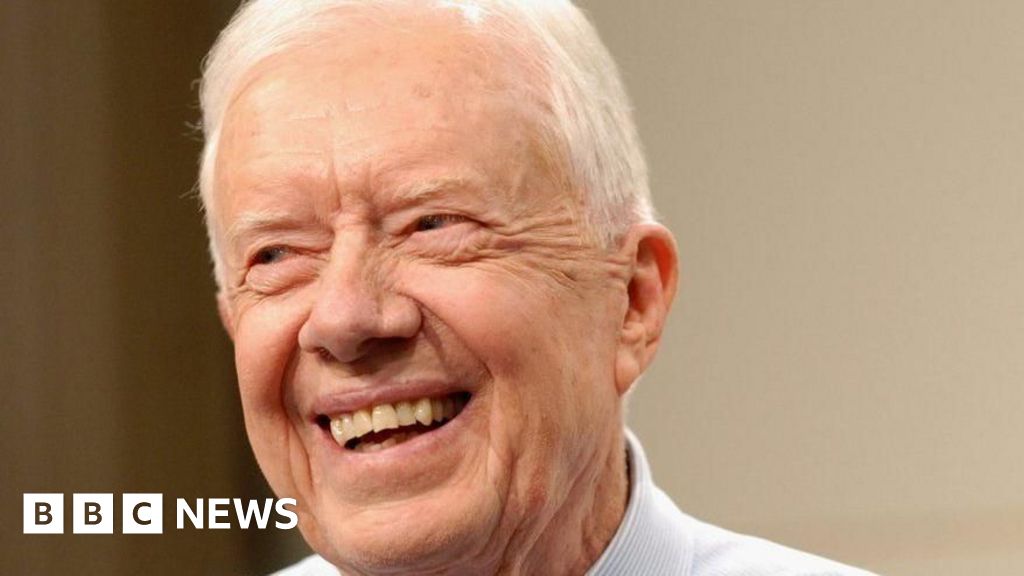

Jimmy Carter, who has died at the age of 100, came to power promising never to lie to the American people.

In the turbulent aftermath of Watergate, the former Georgia peanut farmer pardoned Vietnam draft evaders and became the first US leader to take climate change seriously.

On the international stage, he helped broker a historic peace agreement between Egypt and Israel, but struggled to deal with the Iran hostage crisis and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

After one term in office, he was ousted by Ronald Reagan when he won only six states in the 1980 election.

After leaving the White House, Carter did a lot to restore his reputation: he became a tireless worker for peace, environmental protection and human rights, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The US president, who is the longest-lived in US history, celebrated his 100th birthday in October 2024. He was being treated for cancer and spent the last 19 months in hospice care.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesJames Earl Carter Jr. was born on October 1, 1924 in Plains, Georgia, the oldest of four children.

His segregationist father started the family peanut business, and his mother, Lillian, was a nurse.

Carter’s experiences during the Great Depression and his steadfast Baptist faith formed the basis of his political philosophy.

A star basketball player in high school, he spent seven years in the US Navy – during which time he married Rosalyn, his sister’s friend – and became a submarine officer. But after his father’s death in 1953, he returned to manage the ailing family farm.

The first year was a crop failure due to drought, but Carter grew the business and became rich in the process.

He entered politics on the ground floor, elected to a number of local school and library boards before running for the Georgia Senate.

American politics erupted after the Supreme Court’s decision to desegregate schools.

Being a farmer from a southern state, Carter might be expected to oppose reform, but he had different views than his father.

While serving two terms in the state Senate, he avoided running afoul of segregationists — including many in the Democratic Party.

But after becoming governor of Georgia in 1970, he became more openly supportive of civil rights.

Getty Images

Getty Images“I tell you quite frankly,” he declared in his inaugural address, “that the time of racial discrimination is over.”

He posted pictures of Martin Luther King Jr. on the walls of the Capitol building as the Ku Klux Klan demonstrated outside.

He made sure that African Americans were appointed to government positions.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, he found it difficult to balance his strong Christian faith with his liberal instincts when it came to abortion law.

Although he supported women’s right to abortion, he refused to increase the funding to make it possible.

When Carter began his presidential campaign in 1974, the country was still reeling from the Watergate scandal.

He presented himself as a simple peanut farmer, untainted by the questionable ethics of professional politicians on Capitol Hill.

His timing was excellent. Americans wanted an outsider, and Carter fit the bill.

It was a surprise when he admitted (in an interview with Playboy magazine) that he had “committed adultery many times in my heart.” But there were no skeletons in his closet.

At the beginning, polls showed that only about 4% of Democrats supported him.

However, just nine months later, he unseated incumbent President Gerald Ford, a Republican.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn his first full day in office, he pardoned hundreds of thousands of men who had evaded service in Vietnam – either by fleeing overseas or by failing to register with the local draft board.

One Republican critic, Senator Barry Goldwater, described the decision as “the most disgraceful act a president has ever done.”

Carter admitted that it was the most difficult decision he had to make in his position.

He appointed women to key positions in his administration and encouraged Rosalyn to maintain the national status of first lady.

He advocated (unsuccessfully) for the Equal Rights Amendment to the US Constitution, which promised legal protection against discrimination based on sex.

One of the first international leaders to take climate change seriously, Carter wore jeans and sweaters in the White House and turned off the heating to save energy.

He installed solar panels on the roof, which were later removed by President Ronald Reagan, and passed laws protecting millions of acres of pristine Alaskan land from development.

His televised “fireside chats” were deliberately relaxed, but the approach seemed too casual as problems mounted.

As the American economy slipped into recession, Carter’s popularity began to decline.

He tried to persuade the country to adopt tough measures to deal with the energy crisis – including gasoline rationing – but faced stiff opposition in Congress.

Plans to introduce universal health care also failed in the legislature, while unemployment and interest rates soared.

His Middle East policy began with a triumph when Egyptian President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Begin signed the Camp David Accords in 1978.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut the success abroad was short-lived.

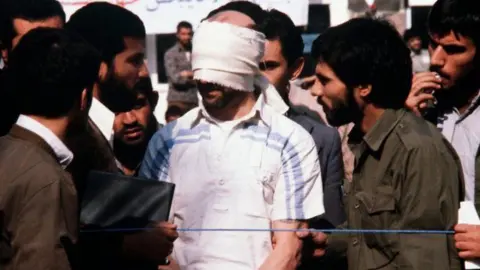

The revolution in Iran, which led to the capture of American hostages, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan became difficult tests.

Carter severed diplomatic relations with Tehran and imposed trade sanctions in a desperate attempt to free the Americans.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAn attempt to rescue them by force ended in disaster, killing eight American soldiers.

The incident almost certainly ended any hope of re-election.

Carter fought off a serious challenge from Senator Edward Kennedy for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1980 and won 41% of the vote in the next election.

But it wasn’t enough to see off his Republican opponent, Ronald Reagan.

The former actor made it to the White House in an Electoral College landslide.

On the last day of his presidency, Carter announced the successful completion of negotiations for the release of the hostages.

Iran delayed their departure until President Reagan was sworn in.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter leaving office, Carter had one of the lowest approval ratings of any US president. But in the years that followed, he did much to restore his reputation.

On behalf of the US government, he led a peacekeeping mission to North Korea that eventually led to the Framework Agreement, the first attempt to reach an agreement to dismantle its nuclear arsenal.

His library, the Carter Presidential Center, became an influential center for the exchange of ideas and programs aimed at solving international problems and crises.

In 2002, Carter became the third U.S. president, after Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, to win the Nobel Peace Prize — and the only one to receive it for post-presidency work.

Getty Images

Getty Images“The most serious and universal problem,” he said in his Nobel lecture, “is the growing gulf between the richest and poorest people on earth.”

With Nelson Mandela, he founded The Elders, a group of global leaders committed to working for peace and human rights.

In retirement, Carter led a modest lifestyle.

He eschewed lucrative gigs and corporate board seats for a simple life with Rosalyn in Plains, Georgia, where both were born.

Carter didn’t want to cash in on his time in the Oval Office.

“I don’t see anything wrong with that; I don’t blame other people for this,” he told the Washington Post. “I never had any ambition to be rich.”

He was the only modern president to return full-time to the house he lived in before entering politics, a one-story, two-bedroom house.

According to the Post, the Carters’ home was valued at $167,000 — less than the Secret Service cars parked outside to protect them.

In 2015, he announced that he was being treated for cancer, the disease that killed his parents and three sisters.

Just a few months after surgery on a broken hip, he returned to work as a volunteer construction worker for Habitat for Humanity.

The former president and his wife began working with the charity in 1984 and have helped repair more than 4,000 homes over the years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe continued to teach Sunday school at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, sometimes hosting Democratic presidential candidates in his class.

In November 2023, Rosalyn Carter died. In a tribute, the former president said his wife was “my equal partner in everything I’ve ever accomplished.”

After celebrating his century a year later, Carter proved that he still has political antennae.

“I’m just trying to do this to vote for Kamala Harris” in the November election, he said.

He managed to vote for her, even though his home state of Georgia ended up voting for Donald Trump.

Carter’s political philosophy contained the sometimes contradictory elements of his small-town conservative upbringing and his natural liberal instincts.

But what really guided his life in public service was his deep-seated religious convictions.

“You cannot divorce religious belief and public service,” he said.

“I have never seen a conflict between God’s will and my political duty. If you break one, you break the other.”

[ad_2]

Source link