Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC

BBC“These,” says Dr. Anas al-Hurani, “the mixed grave.”

The head of the recently open Syrian identification center stands next to two tables covered in the fields. Each laminated white tablecloth has 32 bones of the human thigh. They were neatly aligned and numbered.

Sorting is the first task of this new connection in a long chain from crime to justice in Syria. The “mixed mass grave” means that the corpses were thrown at each other.

Most likely, these bones belong to some hundreds of thousands, which are believed to have been killed by the ripped president Bashar al -Assad and his parents Hafes, who together managed Syria for more than five decades.

If so, says Dr. Al-Hurani, they were among the last victims: they died no more than a year ago.

Dr. Al-Hurani-Sudanto-Odontologist: Teeth can tell you much more about the body, he says, at least when it comes to who the person is.

But from the thigh, laboratory workers in the basements of this squad in Damascus can start the task: they can learn height, gender, age they had; They could also see if the victim was tortured.

Of course, the gold standard in identification is DNA analysis. But, he said, Syria has only one DNA testing center. Many were destroyed during the country’s civil war. And “—with the sanctions many chemicals we need for tests are currently unavailable.”

They were also informed that “parts of the tools can be used for aviation and therefore for military purposes.” In other words, they can be considered “double use” and is prohibited by many Western countries from export to Syria.

Add to this, cost: 250 dollars (£ 187) per test. And, says Dr. al-Hurani, “in a mixed grave you need to do about 20 tests to collect all parts of one body.” The laboratory is completely based on the financing of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The new Islamist rebel government, who has turned over, says what they call “transitional justice” is one of their priorities.

A lot of Syrians who lost their relatives and lost all the traces said the BBC that they are not impressed and disappointed: they want to see more effort from people who are finally chased behind Bashar al-Assad from power Last December after 13 years of war.

Over the years of the conflict, hundreds of thousands have been killed and millions of displaced. And, according to one assessment, more than 130,000 people are forcibly disappeared.

It may take several months at the current speed to determine only one sacrifice from the mixed grave. “It’s,” says Dr. Al-Hurani, “will work for many years.”

Eleven of these “mixed mass graves” are imbued with beautiful, infertile hills outside Damascus. BBC is the first international media that the site has seen. Now the graves are quite visible. In years, as they were dug, their surface fell into a dry, rocky ground.

Companying us Hussein Alawi Al-Mafi, or Abu Ali, as he also calls himself. He was a driver of the Syrian military. “My cargo,” says Abu Ali, “is human bodies.”

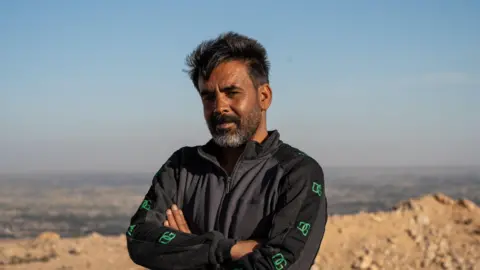

This compact man with salt and pepper’s beard was found thanks to the tireless investigative work of Muaz Mustafa, the Syrian-American-American Executive Director of the Syrian Emergency Group, the American propaganda group. He persuaded Abu Ali to join us, testifies that Muaz calls “the worst crimes of the 21st century”.

Abu Ali transported freight loads on several sites for over 10 years. In this place he came on average twice a week about two years at the beginning of the demonstrations, and then the war from 2011 to 2013.

The routine was always the same. He would go to a military installation or security. “I had a 16m trailer (52 feet). It was not always filled to the edges. But probably I would have an average of 150 to 200 bodies in each load.”

From his cargo he says he is convinced that they are civilians. Their bodies were “chanted and tortured.” The only identification he could see was the numbers written on the corpse or sticking to his chest or forehead. The numbers determined where they died.

According to him, there was a lot of “215” – the notorious content of military intelligence in Damascus, known as “Branch 215”. This is the place we will visit again in this story.

Abu Ali’s trailer had no hydraulic lift to tip and drop his load. When he supported the trench, the soldiers pulled the bodies into the hole one by one. Then the tractor of the front loader “smoothed them out, squeezing them, fill the grave.”

Three people came with outlets from a nearby village. They confirm the history of regular visits of military trucks to this remote place.

And as for a person behind the wheel: how could he do it for a week in week, year after year? What did he say every time he climbed into the cabin?

Abu Ali says he learned to be a dumb servant of the state. “You can’t say anything good or bad.”

When the soldiers threw the corpses into the freshly raised pits, “I just left and looked at the stars. Or looked down to Damascus.”

Damascus, where Milk Audde recently returned after years of fugitives in Turkey. Syria may have been released from the spirit of Assad’s dynastic dictatorship. Milk is still serving a lifetime.

For the last 13 years, it has been closed in the daily process of pain and longing. In 2012, a year after some Syrian residents dared to protest against their president that her two boys disappeared.

Mohammed was still a teenager when he was drafted into the Assad army when the demonstrations were distributed, and the deadly repression of the regime caused a full-scale war.

He hated what he sees, his mother says. Mohammed began to flee and even went to the demonstration. But he was found.

“They broke his hands and beat his back,” the mother says. “He spent three days in the hospital unconscious.”

Mohammed again went awol. “I said he was missing,” Malak says. “But I hid it.”

In May 2012, the 19-year-old girl ended in Mohammed. He was caught with a group of friends. They were shot dead. Milk says there was no official notice. But she always believed he was killed.

Six months later, Mohammed Maher’s younger brother was pulled out of school by officers. It was Mahera’s second arrest. He went for protests in 2011, 14 years old. This led to his first arrest. When a month later he was released from the guard, he found himself in underwear, covered, says his mother, in burning cigarettes, wounds and lice. “He was horrified.”

Malak believes that Maher disappeared from school in 2012 because the authorities found that she was hiding her older brother. Now, for the first time in 13 years, the milk returns to this school, despairing to get the concept of what happened to Maheer.

The new director produces a couple of broken red books. Milk traces the ranks of the names, and then finds the name of the son. In December 2012, a record statement: Maher was expelled from school because he did not appear in lessons for two weeks.

There is no explanation that it is a state that has disappeared. But there is something else: a folder with School records of Mahera was found. His cover is decorated with a photo of the wise Bashar al-Assad, looks thoughtfully. Milk pickets the handle from the desk and writes a photo. Six months ago, this gesture could be deadly.

For many years, the only trims that milk had to cling were two people who said they saw Maher in the “branch 215” – the same military detention center that created so many corpses to convert.

One of the witnesses told the milk that her boy told him something about his parents, what his mother says, he could only know. It was exactly it. “He asked this man to tell me that he was well.” Milk raises and traces tears, puts a pruded cloth in the corners of the eyes.

For milk, as in many Syrians, the fall of Assad was not only a day of joy, but with hope. “I thought there was a 90% likely that Maher would come out of prison. I was waiting for him.”

But she couldn’t even find her son’s name on the prison lists. And so the pulsation of the pain continues to pass through it. “I feel lost and confused,” she says.

Her younger brother Mahmoud was killed by a tank who fired civilians in 2013.

“At least he had a funeral.”