Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Climate and science correspondent

David Bell

David BellThe bones of the British man who died in a terrible accident in Antarctica in 1959 were discovered in the melting glacier.

The remains were found in January by the Polish Antarctic Expedition, as well as wristwatches, radio and pipe.

He was now officially identified as Dennis “Tink” Bell, which fell in Crevasse at the age of 25 when he worked in an organization that became a British Antarctic poll.

“I have long refused to find my brother. It’s just amazing. I can’t overcome it,” David Bell tells BBC News.

British Antarctic poll

British Antarctic poll“Dennis was one of the many brave staff who contributed to the early science and study Antarctica under unusually harsh conditions,” says Professor Dam Jane Francis, director of the British Antarctic.

“Despite the fact that he was lost in 1959, his memory lived among colleagues and the inheritance of polar research,” she adds.

Darius Pukko

Darius PukkoIn July 1959 in London, London, David responded to the door at his family house.

“The Telegram boy said,” I’m sorry to tell you, but it’s bad news, “he says. He came upstairs to tell his parents.

“It was a terrible moment,” he adds.

Talking to me from her house in Australia and sitting next to his wife Ivon, David smiles as stories from childhood in the 1940s.

These are the memories of your younger brother, who admires the magical, adventure older brother.

“Dennis was a fantastic company. It was very funny. Life and soul wherever he is,” David says.

“I still can’t overcome it, but one evening when I, my mother and father came home from the cinema,” he says.

“And I have to say it with justice to Dennis, he put the newspaper on the kitchen table, but he took the motorcycle engine on top, and everything was at the table,” he says.

“I remember his dress style, he always wore a cottage coat. He was just a medium comrade who enjoyed life,” he adds.

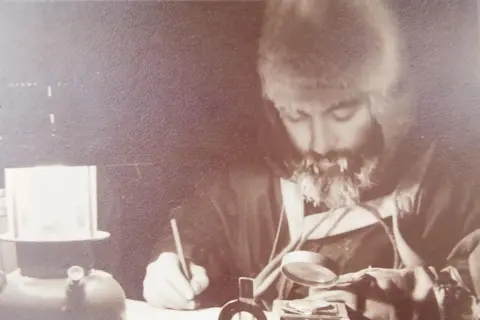

D. Bell

D. BellDennis Bell, according to “Tink”, was born in 1934. He worked with RAF and trained as a meteorologist before going into a poll of the Volkland Islands to work in Antarctica.

“He was obsessed with Scott’s diaries,” David says, citing Captain Robert Scott, who was one of the first people who reached the South Pole and died in an expedition in 1912.

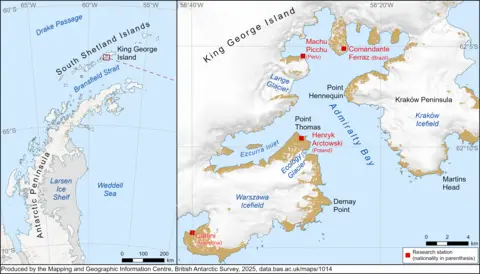

Dennis went to Antarctica in 1958. It was located for two-year use in Admiralty Bay, a small base of the UK with about 12 people on the island of King George, which is approximately 120 kilometers (75 miles) from the northern coast of the Antarctic Peninsula.

Russell Thompson

Russell ThompsonThe British Antarctic poll retains thorough records, and its archivist Joan Hopkins dug detailed reports of the basic camps on Danis’s work and antics on a sharp and “inappropriately isolated” island.

Reading aloud, Mr. Hopkins says, “He is cheerful and hardworking, with a mischievous sense of humor and affection for practical jokes.”

Russell Thompson

Russell ThompsonDennis’s task was to send meteorological balloons and radio reports to the UK every three hours in which the dismissal of the generator in zero conditions participated.

Described as the best chef in the hut, he oversee the food store for the winter when no supplies could get to them.

Antarctica felt even more cut off than today, with extremely limited contact with the house. David recalls records a Christmas message at BBC Studios with his parents and sister Valerie to send him to his brother.

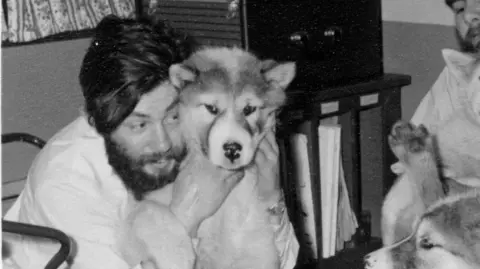

He was most famous for his love for the Huski -the sabbatical, which pulled the sled along the island, and he raised two offspring of dogs.

British Antarctic poll

British Antarctic pollHe also participated in the King George Island poll to create one of the first cartographic cards to a large extent unexplored place.

It was in the poll that the accident happened a few weeks after its 25th anniversary.

On July 26, 1959, in the deep Antarctic winter, Dennis and a man called Jeff Stokes left the base to rise and inspect the glacier.

The accounts in the British records of the Antarctic poll explain what happened further and desperate attempts to save it.

The snow was deep, and the dogs began to show signs of fatigue. Dennis walked forward to encourage them, but he wasn’t skiing. Suddenly he disappeared into the Reve, leaving a hole.

According to the accounts, Jeff Stokes urged the depths, and Dennis was able to shout back. He grabbed the rope that sank down. The dogs stretched to the rope, and Dennis clung to the hole.

But he tied the rope to the belt, perhaps from the corner in which he lay. When he reached his lips, his belt broke and fell again. His friend called again, but this time Dennis did not answer.

“This is a story I will never overcome,” David says.

The basic camp reports about a business -like accident.

“We heard from Jeff (…) that yesterday Tink fell on the reset and was killed. We hope to return tomorrow, allowed by sea ice,” he continues.

Mr. Hopkins explains that another man called Alan Charman died a week earlier, and morality was very low.

“The sleds have come back. We heard sad details. Jeff bit greatly. We no longer risk restoring,” the report said the day after the accident.

After reading the reports again, Mr. Hopkins discovered that earlier in the season was Dennis, which made the coffin for Alan Shaman.

Russell Thompson

Russell Thompson“My mother never overcame it. She couldn’t handle his photos and couldn’t talk about him,” David says.

He recalls that two men on the basis of Dennis visited the family, bringing a sheepskin as a gesture.

“But there was no conclusions. There was no service; there was nothing. Just Dennis left,” David says.

British Antarctic poll

British Antarctic pollAbout 15 years ago, David addressed that Rod Jones, chairman of the British Antarctic monument.

Since 1944, 29 people have been killed while working on the British territory of Antarctic on scientific missions, Trust reports.

The genus organized a journey for relatives of some of the 29 to see a spectacular and distant place where their loved ones lived and died.

David joined the expedition named South 2015.

“The captain stopped in the places and gave four to the loud sirens,” he says.

The sea ice was too thick to David reached his brother’s house on King George’s island.

“But it was very, very moving. He raised pressure, weighing from my head,” he says.

It gave him a sense of closing.

“And I thought it would be,” he says.

Darius Pukko

Darius PukkoBut on January 29 this year, a team of Polish researchers working from the Polish Antarctic Station Henryk Artisk came across something practically on the doorstep.

Dennis was found.

Some bones were on free ice, and the rocks laid at the foot of the ecology on the island of King George. Others were found on the surface of the glacier.

Scientists explain that fresh snowfall was inevitable, and they postponed the GPS marker so that their “colleague’s colleague” is not lost.

Darius Pukko

Darius PukkoThe team of scientists consisting of Peter Kitel, Pauline Borouki and Arthur Hiner at the University of Lodz, Dariusz Pukko at the Polish Academy of Sciences and colleagues -researchers Arthur Admek carefully saved the remains on four trips.

It is a dangerous and unstable place, “crossed by blood,” and with slopes up to 45 degrees, reports Polish Command.

Climate change causes dramatic changes in many Antarctic glaciers, including an ecology glacier that is experiencing intense melting.

“The place where Dennis was found does not match the place where he went missing,” the team explains.

“The glaciers, under the influence of gravity, move a lot of ice, and with it Dennis made his journey,” they say.

Fragments of ski pillars, remains of oil lamps, glass containers for cosmetics and fragments from military tents were also collected.

“Every effort was made to make Dennis return home,” the team said.

“This is an opportunity to revise the contribution of these people, and the opportunity to promote science and what we have done in Antarctic for decades,” adds Rod Jones.

Darius Pukko

Darius PukkoDavid still seems crowded with news and repeats how grateful he is to Polish scientists.

“I’m just sad that my parents never saw this day,” he says.

David will soon visit England, where he and his sister Valerie are planning to finally put Dennis to rest.

“It’s great; I’m going to meet my brother. We can say we should not be delighted, but we have it. He’s found – he’s coming home now.”