Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC Korean – It’s Hapcheon

BBC/Hyojung Kim

BBC/Hyojung KimAt 08:15, August 6, 1945, when the nuclear bomb fell like a stone across the sky over Hirosima, Li Jung Sun walked on his way to elementary school.

Now the 88-year-old waved her hands, as if trying to push his memory.

“My father was going to go to work, but he suddenly came back and told us to evacuate immediately,” she recalls. “They say the streets were filled with dead – but I was so shocked that everything I remember was crying. I just cried and cried.”

Mi Li Lee that “only their eyes were melted,” he only says that an explosion, equivalent to 15,000 tons of TNT, enveloped the city of 420,000 people. What remained after there was too corpses to determine them.

“Atomic bomb … it’s such a terrible weapon.”

80 years have passed since the United States has undermined the “little boy”, the first in the history of the atomic bomb of humanity over the Hiroshima center, about 70,000 people were instantly killed. Tens of thousands would be killed in the coming months of radiation, burns and dehydration.

The destruction that occurred by Hiroshima and Nagasaki explosions, which ended the decisive end of both World War II, and the Japanese imperial government through Great Asia-has been well documented over the last eight decades.

Less known is that about 20% of the immediate victims were Koreans.

Korea was a Japanese colony 35 when the bomb was dropped. 140,000 Koreans estimates that they lived in Hiroshim at the time – many moved there from forced mobilization of labor or survival during colonial exploitation.

Those who survived the atomic bomb, along with their descendants, continue to live in the long shadow of this day-wovenness with mutilated, pain and decades of struggle for justice that remains unresolved.

Gets the image

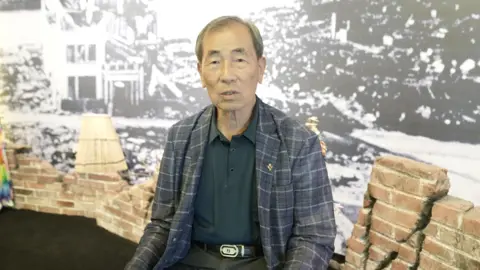

Gets the image“Nobody takes responsibility,” says Shim Jin-Tsa, the 83-year-old survived. “Not the country that threw a bomb. Not a country that couldn’t defend us. America never apologized.

Now Mr. SHIM lives in Hapcheon, South Korea: a small county that became the home of dozens of survivors, like him and Mrs. Lee, was called “Hiroshima Korea”.

For Mrs. Lee, the shock on this day did not go out – he crashed into her body as a disease. Now she lives with skin cancer, Parkinson’s disease and angina, conditions that stem from poor bleeding to the heart, which is usually manifested as chest pain.

But what weighs more is that the pain did not stop with her. Her son Ho-Chan, who supported her, was diagnosed with renal failure and dialysis is waiting.

“I believe this is due to the impact of radiation but who can prove it?” Ho-Chang Lee says. “It is difficult to check out scientifically – you will need a genetic testing that is grueling and expensive.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) has stated the BBC that it collected genetic data between 2020 and 2024 and will continue further research by 2029. It will “consider expanding the determination of victims” to those who survived the second and third generation “only” if the results are statistically significant, “the report said.

Of the 140,000 Koreans in Hiroshima, many were grabbed during the bombing.

Surrounded by mountains with small agricultural land, it was a difficult place for life. The crops were confiscated by Japanese occupiers, drought destroyed the land, and thousands of people left a rural country for Japan during the war. Some of them were forcibly called; Others were enlisted by the promise that “you could eat three meals a day and send children to school.”

But in Japan, Koreans were second-class citizens, given the most difficult, dirty and most dangerous jobs. Mr. Shim says his father worked at the munition plant as a forced worker, while the mother killed his nails into wooden ammunition.

After the bomb, this work distribution is translated into dangerous and often deadly work for Koreans in Hiroshima.

BBC/Hyojung Kim

BBC/Hyojung Kim“Korean workers had to remove the dead,” says Mr. Shim, who is the director of the Hapcheon branch of the Korean Association of Victims of the Atomic Bomb, says BBC Korean. “At first they used stretchers, but there were too many bodies. In the end, they used dust products to collect corpses and burned them in the school yards.”

“Mostly this was done by the Koreans. Most post -war cleaning and ammunition was done by us.”

According to the GyeongGi Welfare Fund, some survivors were forced to clean the rubble and restore bodies. While Japanese evacuated relatives escaped, Koreans without local ties remained in the city, exposed to radioactive fall – and with limited access to medical care.

The combination of these conditions – poor treatment, dangerous work and structural discrimination – all contributed to the disproportionately high number of Koreans.

According to the Korean Association of Victims of the Atomic Bomb, the death rate in Korea was 57.1%compared to the total speed of about 33.7%.

About 70,000 Koreans were exposed to the bomb. By the end of the year, about 40,000 were killed.

After the blasts that led to the surrender of Japan and the subsequent release of Korea, about 23,000 survivors in Korea returned home. But they were not welcomed. These disfigured or damn, they collided with prejudices even in the homeland.

“Hapcheon already had a colony,” explains Mr. Shim. “And because of this image, people believed that those who survived in a bomb also have skin diseases.”

Such a stigma made those who survived silent about their difficult position, he adds, believing that “survival came before pride.”

Ms Lee says she saw it “with her own eyes.”

“People who were badly burned or very poor treated the terribly,” she recalls. “In our village, some people had backs and faces are so scary that only their eyes were visible. They were thrown away from marriage and avoided.”

Poverty and difficulty came with the stigma. Then came the diseases without the exact cause: skin diseases, heart condition, renal failure, cancer. The symptoms were everywhere – but no one could explain them.

Over time, the focus moved to the second and third generation.

BBC/Hyojung Kim

BBC/Hyojung KimKhan Chong-SN, who survived the second generation, suffers from avascular necrosis in the hips and cannot walk without dragging himself. Her first son was born with cerebral paralysis.

“My son never walked a single step in his life,” she says. “And my son-in-law treated me awful. They said, ‘Did you give birth to a baby, and you are also crippled here to ruin our family? “

“This time was absolutely hell.”

For decades, even the Korean government has been actively interested in its victims, since the war with the northern and economic struggle was considered as higher priorities.

And only in 2019 – over 70 years after the bombing – Mohw released its first detection report. This survey was mainly based on questionnaires.

In response to the BBC requests, the ministry explained that by 2019 there was “no legal basis for financing and official investigations.”

But two separate studies have shown that second -generation victims were more vulnerable. First, since 2005, he showed that the victims of the second generation have been much more likely than the common population to suffer from depression, heart disease and anemia, and the second since 2013 has found that the level of registration of disability was almost twice as much as the country’s average.

Against this background, Ms. Khan is distrustful that the authorities continue to ask for evidence to recognize her and her son as Hiroshima’s victims.

“My illness is proof. My son’s disability is proof. This pain passes generations, and it is visible,” she says. “But they don’t admit it. So what should we do – just to die without acknowledged?”

Only last month, July 12, Hiroshima officials first visited Hapcheon to put flowers on the memorial. While former Prime Minister Hatoyam Yukio and other private figures came earlier, this was the first official visit of current Japanese officials.

“Now in 2025, Japan is talking about peace. But peace without apology is meaningless,” says Yunka Ichiba, a long-time Japanese activist of peace, who spent most of his life, playing for the victim of Korean Hiroshima.

She notes that the visit officials did not mention or apologize for how Japan treated Korean people before and during World War II.

BBC/Hyojung Kim

BBC/Hyojung KimDespite the fact that several former Japanese leaders have apologized and remorse, many South Koreans view these moods as insincere or insufficient without official recognition.

Ms Ichiba notes that Japanese textbooks are still omitted the history of the colonial past of Korea – as well as his victims of the atomic bomb – they say that “this invisibility only deepens injustice.”

This adds to the fact that many see as a broader lack of responsibility for Japan’s colonial heritage.

Heo Chong-gu, the director of the Red Cross support department, said: “These issues … must be resolved as long as the survivors are still alive. For the second and third generation, we must gather evidence and testimony until it is too late.”

For those who survived, like g -shim, it is not just about compensation – it is a recognition.

“Memory is more important than compensation,” he says. “Our bodies remember that we have survived … If we forget it, it will happen again. And if -no, there will be no one to tell the story.”