Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

[ad_1]

BBC

BBCThere are few more obvious signs of the destructive force that Hurricane Beryl brought to Barbados in July than the scene at the temporary dockyard in the capital, Bridgetown.

Many mutilated and cracked ships are piled up, with gaping holes in their hulls, broken rudders and broken cabin windows.

But they were the lucky ones.

At least they can be repaired and returned to the sea. Many others drowned, taking their entire family’s income with them.

When Beryl attacked Barbados, the island’s fishing fleet was devastated in a matter of hours. About 75% of the active fleet was damaged, 88 boats were completely destroyed.

Charles Carter, who owns a blue and black fishing vessel called the Joyce, was among those affected.

“It was very bad, I can tell you. I had to change both sides of the hull, right down to the waterline,” he says, pointing to the now pristine boat in front of us.

It took months of restoration and thousands of dollars to bring it back to this point, during which time Charles was barely able to fish.

“This is my life, my income, fishing is all I do,” he says.

“The fishing industry is a mess,” echoes his friend, Captain Eurydes. “We’re just trying to put the pieces back together.”

Now, six months after the storm, there are signs of calmer waters. On a warm Saturday, several repaired vessels were returned to the ocean with the help of a crane, a trailer and some government support.

To see Joyce on the water is a welcome sight for all anglers in Barbados.

But Barbadians are keenly aware that climate change means more active and powerful hurricane seasons in the Atlantic – and it could be another year or two before the fishing industry is hit again. Beryl, for example, was the earliest Category 5 storm on record.

Few understand the scale of the problem better than the island’s Chief Fisheries Officer, Dr. Shelley Ann Cox.

“Our captains reported that sea conditions had changed,” she explains. “The waves are higher, the sea surface temperature is much higher, and they have a hard time catching flying fish early in our pelagic season.”

The flying fish is the national symbol of Barbados and a key part of the island’s cuisine. But climate change has been damaging stocks for years.

Oistins Fish Market in Bridgetown still has flying fish available, as well as marlin, mahi mahi and tuna, although only a few stalls are open.

One of them, Cornelius Carrington, of Freedom Fish House. filleting kingfish with the speed and agility of a man who has spent many years with a fish knife in hand.

“Beryl was like a surprise attack, like an ambush,” Cornelius says in his deep baritone, drowning out the market chatter, reggae, and the thump of wranglers on the cutting boards.

Cornelius lost one of his two boats in Hurricane Beryl. “This is the first time a hurricane like this has come from the south, usually storms hit us from the north,” he said.

Although his second boat has kept him afloat financially, Cornelius believes that climate change is increasingly present in the fate of fishermen.

“Now everything has changed. The tides change, the weather, the temperature of the sea, the whole scheme has changed.’

The effects are also being felt in the tourism industry, he says, with hotels and restaurants struggling to find enough fish to meet demand each month.

For Dr. Shelley Ann Cox, public education is key, and she says the message is getting through.

“Perhaps because we are an island and so connected to water, people in Barbados can speak well about the impact of climate change and what it means for our country,” she says.

“I think if you talk to the kids as well, they know the subject well.”

To see for myself, I visited a high school – Harrison College – as a member of a local NGO, the Caribbean Youth Environmental Network (CYEN), to talk to members of the school’s environmental club about climate change.

CYEN representative, Sheldon Marshall, is an energy expert who asked students about greenhouse gases and steps they can take at home to reduce carbon emissions on the island.

“How can you young people from Barbados help change climate change?” he asked them.

After an engaging and lively discussion, I asked the students how they felt about Barbados being on the front lines of global climate change despite having a small carbon footprint in itself.

“Personally, I take a very pessimistic view,” said 17-year-old Isabella Fredricks.

“We are a very small country. No matter how much we try to change, if the big countries—the major polluters like America, India, and China—don’t change, everything we do will be pointless. “

Her classmate Tenusha Ramsham is a little more optimistic.

“I think all the great leaps in history have been made when people collaborated and innovated,” she asserts. “I don’t think we should be completely disillusioned because research, innovation, technology creation and education will ultimately lead to the future we want.”

“I feel like if we can convey to the world’s superpowers the pain we feel seeing this happening to our environment,” adds 16-year-old Adrielle Baird, “then it will help them understand and help us work together to find ways to fix it.” problems we see.’

For the young people of the island, their very future is at stake. Sea level rise now threatens the existence of small islands in the Caribbean.

It’s the moment Barbados Prime Minister Mia Motley has become a global advocate for change – in her speech at COP29 calling for more action to tackle the looming climate catastrophe and calling for economic compensation from the industrialized world.

On its shores and in the seas, Barbados seems to be under siege, with problems from coral bleaching to coastal erosion being tackled. The impetus for action is the youth of the island, but the older generations have witnessed the changes taking place.

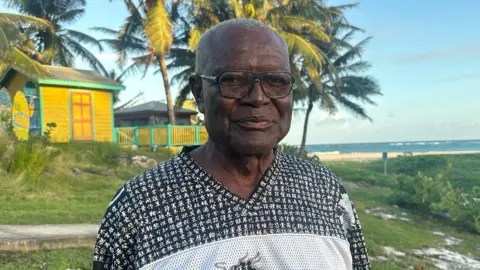

Stephen Bourne has fished the waters around Barbados all his life and lost two boats in Hurricane Beryl. As we look out over the coastline from a dilapidated beach bar, he says the island’s sands have shifted before his eyes.

“This is an elemental attack. You see it taking away the beaches, but years ago you sat here and saw the water’s edge close to the sand. Now you can’t because there is so much sand.”

Coincidentally, the Home Secretary, Wilfred Abrahams, who is responsible for national disaster management, was in the same bar where I spoke to Stephen.

I told him that this must be a difficult time for disaster management in the Caribbean.

“The whole landscape has completely changed,” he replied. “It used to be rare for a Category Five hurricane to happen in any given year. Now we get them every year. So the intensity and frequency is a concern.”

Even the length of hurricane season has changed, he says.

“We used to have a rhyme: June, too soon; July, waiting; October, it’s all over,” he tells me. Extreme weather events like Beryl have rendered such an idea obsolete.

“What we can expect has changed, what we’ve been preparing for all our lives and what our culture is built around,” he adds.

Fisherman Stephen Bourne had hoped to retire before Beryl. Now, he said, he and the other islanders have no choice but to keep going.

“Being afraid or something like that doesn’t make sense. Because we have nowhere to go. We love this stone. And we will always be on this rock.”

[ad_2]

Source link