Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Quentin SomervilleBBC NEWS, reporting Bilazek in eastern Ukraine

A white armored police minibus accelerates into the eastern Ukrainian city of Bilaserki, a steel cage installed throughout the body to protect it from Russian drones.

They have already lost one van, a straight blow from the drone to the front of the car; The cell and powerful equipment for drones on the roof provide additional protection. But it is still dangerous to be here: police known as “white angels” want to spend as little time as possible in Bilaser.

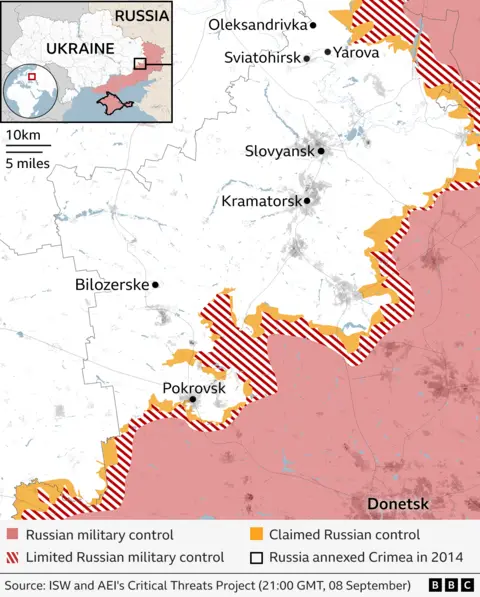

A small, beautiful mining city, just nine miles (14 km) from the front line, slowly destroyed by the summer offensive of Russia. The local hospital and banks have long closed. Stucco buildings on the city square are destroyed by drones, the trees along the avenues are broken and scattered. Neat rows of cottages with corrugated roofs and well -arranged gardens pass past the car windows. Some of them are intact, others burned the shells.

The approximate assessment is that 700 residents remain in the biloser of the pre -war number of 16,000. But their little evidence is already being abandoned.

218,000 people estimate need evacuation from the Donetsk region, in eastern Ukraine, including 16,500 children. The area, which is crucial for the country’s defense, is a major blow to the Russian invasion, including the daily attacks of drones and missiles. Some cannot leave, others do not want. Authorities will help evacuate them in the areas, but they cannot look again as soon as they do not threaten. And despite the growth of threat from Russian drones, there are those who risk rather than leave their homes.

Police are looking for a one woman who wants to leave. Their van can’t do it on one of the roads. So, on foot, the policeman goes in search, the hum of the small Jerome and his invisible defense recedes when he heads across the lane.

In the end, he finds a woman under the cornices of her cottage that on the door, reading “People live here”. She has dozens of bags and two dogs. It is too much to prevent the police: they already have evacuated, and their things are stuffed in a white minibus.

The woman is confronted with the choice – leave behind her things or stay. She decides to wait. Another evacuation team will soon appear here, and they will also take her things.

Stay or go-is a calculation of life or death. In July this year, civil sacrifices in Ukraine reached a three -year maximum, according to the latest United Nations, with 1674 people killed or victims. Most are found in urban cities. In the same month, the largest number was killed and dried from a short range from the beginning of a full -scale invasion, the UN said.

The nature of the threat to civilians in the war has changed. Where once artillery and missile strikes were the main threat, they are now faced with the relocation of first -person drones (FPV) and then hit.

When the police leaves the city, there is an old man who pushes the bike. On that day he is the only soul I see on the streets.

According to the UN, most of those who remain in the towns engaged in the elderly who make up a disproportionate number of civil victims.

He orders me to move toward the road, because of the path of non-existent movement. Volodymyr Ramanuk is 73 years old and risks his life for two culinary pots he collected on the back of his bike. His sister’s house was destroyed in a Russian attack, so he came today to save the pots.

I am not afraid of drones, I ask. “What it will happen. You know, at the age of 73, I’m no longer afraid. I have already lived my life,” he says.

Darren Konve/BBC

Darren Konve/BBCHe is in no hurry to leave the streets. Former football referee, he slowly removes the folded card from his jacket pocket and shows me his official football arbitratory card. This is dated April 1986 – the month of Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

He is from the west of Ukraine and can return there from harm. “I stayed here for my wife,” he tells me. She had several operations and could not travel. And with that he leaves and heads home to take care of his wife, two metal pots at the back of a bicycle rattles when he moves down the empty street.

Slavyansk even further from the front, 25 km from it and is facing another threat of drone. Ukrainians from their engines who knock the engines were called “flying mopeds”. Roy is often attacked by Slavic. There is a change in the buzz drone before it immersed and then explode.

At night, Nadia and Oleh hearing them, but they still do not leave Slavic. They poured blood and sweated into this land – and tears were also on their son’s grave.

Sergius was 29, a lieutenant in the army, killed by a cluster bomb near Svatov in November 2022. He and his father Oleh first fought in 2015 against the Russians in Donbass. They worked nearby like a sappers.

Sergius’s triangular tomb sits on the slope of the hills overlooking Slavyansk, his portrait and card of Ukraine on a polished black stone.

Darren Konve/BBC

Darren Konve/BBCNadia, 53, visits frequently. In the afternoon I meet her, Russian artillery landed on a nearby slope. But she pays little attention to the fuss around the grave and whispered sweet burrows to her dead son.

“How can you lose a place where you were born, where you grew up, where your baby grew up, where you found your last vacation?” She tells me through tears. “And then live your whole life with the feeling that you never visit this place again – I can’t even imagine it now.”

But her husband Ole, 55, admits that they will have to leave if the fight is approaching. “I will not stay here, the Russians would immediately put me a goal,” he says. Before that, they will remain under nighttime drones so that they can stay near the last place of the son’s rest.

Life problems do not stop when the war comes. All Olha Zaiets is a time to recover from cancer surgery. Instead, the 53-year-old and her husband, Alexander Ponomarenko, 59, had to run away from the house to Oleksandriv. The Russians were only 7.5 km, and the shelling became intensive. Their post -post was killed in the Russian bombing, and the school principal too.

“There was a strike – the rocket hit the nearby house. And the explosive wave broke our roof tile, blew the door, windows, gates. We just left, and two days later it hit. If we were there, we would die,” she explains.

Darren Konve/BBC

Darren Konve/BBCNow they live temporarily, in a borrowed house in Svyatogirsk. It’s not much better. We can hear the shelling outside, the front line is closer every day. But it will have to be done. They have nowhere else to go.

“Yes, we will have to go on, but we do not know how and where,” she says in a room overflowing with her things, still waiting to be unpacked. Their savings of life went to hospital accounts and now they are unable.

On Tuesday, they left the city to collect the Olha test results. The news was good, and she would not have to undergo chemotherapy. “We were happy, we felt we were flying on the wings,” she said.

But while they were gone, Russia bombed the neighboring city of Yarov, 4 km. It took only 11am, and the elderly people left their homes and gathered to gather their pensions. About 24 were killed and 19 injured in one of the most deadly strikes in the war.

In Telegram, the head of the administration of Donetsk Vadim Filashkin refused the attack. “It’s not a war – it’s pure terrorism.”

“I call everyone,” he said, “take care of yourself. Evaculate to safer regions of Ukraine!”

Additional Libovo Scholaudko reporting