Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Soutik BiswasIndia’s correspondent

Vivek R NAIR

Vivek R NAIROn the eve of Onama, the most joyous festival in Kerala in India, the 45-year-old Sabhan lay trembling in the back of the ambulance, which flows into the inconsistency when her family sent her to the medical college hospital.

Just a few days earlier, the woman is dylito (formerly known as untouchable), who earned live fruit juices in the spill in the village in the area of the low -pistle, complained about nothing more disturbing than dizziness and high blood pressure. Doctors prescribed pills and sent her home. But her state of spiral at a terrible speed: anxiety gave way to the fever, the fever for violent chills, and September 5 – the main day of the festival – Sabhan was died.

The guilty was Naegleria Fowleri – commonly known as an amoeba that uses a brain – an infection that is usually contracting through the nose in fresh water, and so rare that most doctors never face a career. “We were powerless to stop this. We learned about the illness only after the death of the faded,” says the Zhitta Katiradat, the victim’s cousin and the famous social worker.

More than 70 people were diagnosed with Kerala this year, and 19 died of an amobes who use the brain. Patients ranged from three months to 92-year-old man.

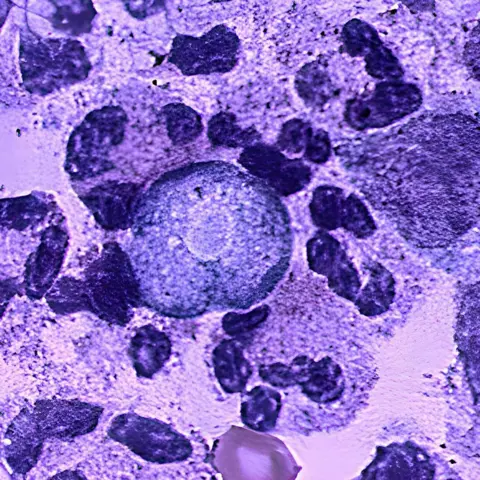

Usually it feeds on bacteria in warm fresh water, this single -skinned body causes an almost deadly brain infection known as primary amoebic meningocephalitis (PAM). It enters the nose during swimming and quickly destroys brain tissues.

Kerala began to detect cases in 2016, only one -two a year, and until recently, almost everyone was deadly. New study Only 488 cases have been found, registered in the world since 1962 – mainly in the US, Pakistan and Australia. And 95% of the victims died of the disease.

Group Universal Images via Getty Images

Group Universal Images via Getty ImagesBut in Kerala, survival appears to be improving: last year there were 39 cases with 23% fatal outcome, and almost 70 cases of about 24.5% were reported this year. Doctors say the increase in the number reflects the best detection due to the modern laboratory.

“The cases are increasing, but death falls. Aggressive tests and early diagnosis improved survival – a strategy for Kerala,” said Aravind Regicum, head of the infectious disease department at the Medical College and Hospital in Tirovanthopur, the state capital. Early detection allows for individual treatment: narcotic cocktail antimicrobials and steroids focused on amoeba can save life.

Scientists have discovered about 400 species of free live amounts, but it is known that only six cause the disease in humans – including Naegleria Fowleri and Acanthamoeba, both can infect the brain. In Kerala, public health laboratory can now identify five major pathogenic types, officials say.

The great dependence of the southern state on groundwater and natural reservoirs makes it especially vulnerable, especially since many reservoirs and wells are contaminated. For example, last year, a small set of cases was associated with cooked cannabis mixed with a reservoir mixed with reservoirs – a risky practice that emphasizes how contaminated water can become a pipeline for infection.

Kerala has almost 5.5 million wells and 55,000 reservoirs – and millions draw daily water only from wells. The fact that ubiquity does not allow to consider wells or reservoirs as simple “risk factors” – they are the basis of life in the state.

“Some infections occurred in people who bathe in the reservoirs, others of the pools, and even through the nasal rinsing of the water, which is a religious ritual. Be in a contaminated reservoir or well, the risk is real,” says Anish TS leading an epidemiologist.

NP NP

NP NPThus, public health authorities tried to respond to the scale: in the end of August, there were 2.7 million wells in the end of August.

Local authorities put significant boards around the reservoirs that prevent bathing or swimming and caused the healthcare law to force regular chloruring of swimming pools and water tanks. But even with such measures, the reservoirs cannot be realistically chlined – the fish will die – and the police source in the village is more than 30 million disabled people.

Now the officials emphasize the awareness of the ban: households call for cleaning tanks and swimming pools, use clean warm water for the nasal eggs, keep children away from garden spreaders and avoid dangerous reservoirs. It is recommended to protect the nose by keeping the nose over the water, using nose plugs and avoiding the precipitation in stagnant or unprocessed fresh water.

However, hitting the balance between public upbringing about real risks – the use of unprocessed fresh water – and avoiding fear that can disturb daily life is a difficult task. Many say that despite the recommendations issued for more than a year, forced execution remains clumsy.

“This is a difficult problem. In some places (hot sources) signs are placed to prevent the possibility of amoeba in the water source. This is not virtually most of situations, since the amoeba can be present at any source of unprocessed water (lakes, ponds, swimming pools), Dennis Kyle, professor of infectious diseases and cellular biology.

“In more controlled conditions, frequent monitoring of proper chlorus can significantly reduce the chances of infection. These include pools, sites and other man-made recreational water activities,” he said.

Abhishek Chinnappa/Getty Images

Abhishek Chinnappa/Getty ImagesScientists warn that climate change increases the risk: warmer waters, more summer and fever create perfect conditions for amoeba. “Even height 1C can spread in the tropical climate of Kerala and water pollution, fueled it further, feeding the bacteria consuming amoeba,” says Prof.

D -R Kyle adds a note of caution, noting that some past cases may simply not be recognized, and anmebo is not defined as a reason.

This uncertainty can make treatment even more difficult. The current drug cocktails are “insufficient”, explains Dr. Kyle, adding that the rare survivors becomes the standard. “We lack enough data to determine whether all drugs are useful or necessary.”

Kerala can catch more patients and save more lives, but the lesson reaches far beyond. Climate change can rewrite the disease map – and even the most rare pathogens may not remain uncommon.