Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC World Service

Odil Amin Akhon

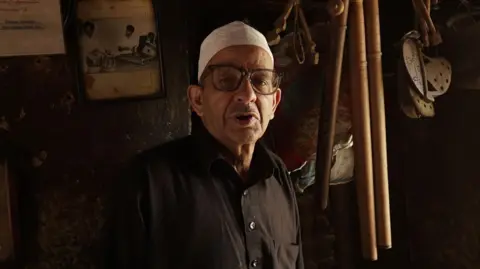

Odil Amin AkhonIn the quiet, narrow strip of Srinin in the Indian administrated cashmere, a small, dimly illuminated workshop is one of the last content of the disappearing ship.

Inside the store sits the hum of Mohammed ZAZ, which is supposed to be considered the last artisan of the region, which can make Santuro by hand.

Santura is a trapezoidal musical instrument in the form of a trapezoid, similar to a dulcimer that plays with prayers. He is known for his crystalline tone, reminiscent of the bell and for centuries was a musical signature of Kashmir.

Mohammed’s Gulya belongs to the pedigree of the masters, who have built string instruments for more than seven generations. Zaz’s name has long been synonymous as the creators of Santura, slave, scarecrows and sequar.

But in recent years, the demand for manual tools has decreased, replaced by machine versions that are cheaper and faster. At the same time, the thick music has changed, which adds a decrease.

“With hip -hop, rap and electronic music that dominates Kashmir’s sound landscape, young generations are no longer combined with the depths and discipline of traditional music,” says Shabir Ahmad Mir, music teacher. As a result, the demand for Santur collapsed, leaving masters without students and a sustainable market, he adds.

Odil Amin Akhon

Odil Amin AkhonIn his centuries -old shop, Mohammed sits next to the hollow block of wood and worn iron instruments – the quiet remains of the tradition of fading.

“There is no one left (to continue the craft),” he says. “I’m the last.”

But it wasn’t always that way.

For many years, the famous Sufi and folk artists have played in the Santura made by hand Mohammed.

The photo at his store shows that Maestros Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma and Bhajan Sopori perform with their tools.

It is believed that it took place in Persia, Santurta reached India in the 13th or 14th century, spreading through Central Asia and the Middle East. In Kashmir, she occupied different identities, becoming the main in Sufi poetry and folk traditions.

“Initially, part of the Sufiana Mausiqi (the musical tradition of the ensemble), Santur had a soft, folk tone,” says Mr. Mir.

Panditis sewed Kumar Sharma later adapted to Indian classical music, he says, adding lines, refining the bridges for a richer resonance and introducing new gaming techniques.

Bhajan Sori, who has Kashmir’s roots, “deepened his tonal range and filled it with a Sufi expression,” adds Mr.

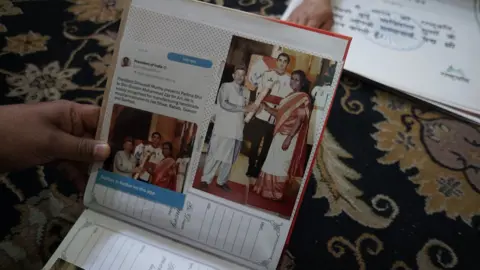

One photo shows Mr. Gula Mohammed, who receives Sri’s supremacy from Drupady Murma in 2022, honored for the skills of the fourth largest Indian Civic Prize.

Gets the image

Gets the imageMohamed Mohammed was born in the 1940s in Zaine Cadal, a neighborhood named after a landmark bridge that once served a trade and commercial culture in Kashmir. Growing up, he was surrounded by the sounds and tools of his family.

Health problems forced him to leave his official education at an early age, and then he began to study art that produces Santura from his father and grandfather – both masters.

“They taught me not only how to make the instrument, but also how to listen – to the tree, the air and the hands that will play,” he said.

“My ancestors called the courts of local kings and often asked to build tools that could calm the hearts,” he says.

In its workshop a wooden bench, laid out of meat and strings, lies near the skeletal frame of the unfinished Santura. The air smells slightly with outdated walnuts, but the cars are not visible.

Mr. Gulu Mohammed suggests that machine tools do not have the heat and depth of those created by hand and the sound quality is nowhere to be close.

Creating a Santura is a slow, intentional process, says the master. It starts with the choice of right timber, at least five years old. Then the body is cut and blended for optimal resonance, and each of the 25 bridges is exactly in shape and placed.

More than 100 lines have been added, then a painstaking setting process, which can take several weeks or even months.

“It’s a craft of patience and perseverance,” he says.

Gets the image

Gets the imageIn recent years, the influence of social media has visited the Grud Mohammed seminar, sharing their history on the Internet. He appreciates attention, but says it did not lead to real efforts to preserve the craft or its heritage.

“It’s good people,” he says, “but what will happen when I left?”

With three daughters who spend other careers, the family has no one to continue their work. For many years he had proposals – state grants, promises of students, even offers of the state crafts department.

But Mr. Mohammed says that “he does not seek glory or mercy.” What he really wants is anyone to move the art forward.

Now, in his eighties, he often spends hours near the unfinished Santur, listening to the silence of what else needs to be completed.

“It’s not just woodworking,” he says.

“This is poetry. Language. I give the tool.

“I hear Santuro before he plays. It’s a secret. This is what he needs to be conveyed,” he adds.

Because the world outside covers the present, the workshop of Gulam Mohammed remains intact sometimes – slow, silent and filled with the aroma of walnut and memory.

“Tree and music,” he says, “both die if you don’t give them time.”

“I want the one who really loves the craft, to take it forward. Not for the money, not for the camera, but for the music.”

Keep up the BBC News India Instagram. YouTube, Youter and Facebook is Facebook at Facebook..