Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

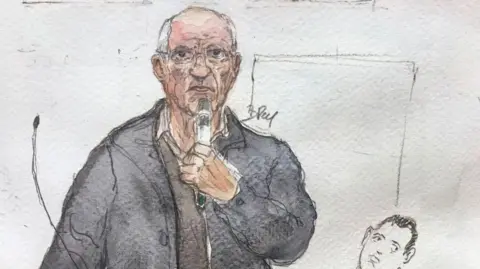

BBC Paris correspondent

Gets the image

Gets the imageIt was to be a defining, catalytic moment for French society.

Terrible, but unchanged. One.

The Primorsky city of Vanis, in the south of Brittany, carefully prepared a special place and a separate amphitheater overflow.

Hundreds of journalists were accredited for a process that certainly dominates France’s headlines during the entire three -month duration and made the unfortunate audience resist a crime that was too often thrown into the sidelines.

Warning: Some details of this story are disturbing

The comparisons were rapidly made with and expectations related to last year’s Mass Rape Pelicot in the south of France, and the mass global attention he attracted.

Instead, the trial of France’s most prolific pedophile Joel Le Skarnek, a retired surgeon who confessed to the court of rape or sexual attack for 299 people, almost all of them children – ends this Wednesday among the wide disappointment.

“I am exhausted. I’m angry. I don’t have great hope now. Society seems completely indifferent. It is scary to think (rape) can happen again,” said one of the victims of Le Scouarnec, 36 -year -old Manon Lemine.

Benoit Peyrucq/AFP

Benoit Peyrucq/AFPMs. Lemuan and about 50 other casualties who have been in a clear lack of public interest in the trial, created their own company on the pressure of the French authorities, accusing the government of ignoring the “landmark” case that exposed the “true laboratory of institutional failures”.

The group asked why the parliamentary commission was not created, as in other high -profile abuse, and it was said to feel “invisible” as if “a large number of victims prevented us from recognizing.”

Some of the victims, most of whom have initially decided to testify, decided to reveal their identity in public – even putting for photos on the steps of the court building – in the hope that France paid more attention and possibly learning lessons about the culture of respect, which helped with prestigious surgeons.

The crimes for which Le Souarnec trial occurred from 1998 to 2014.

“It’s not normal that I need to show my face (but) I hope what we are doing now will change everything. That’s why we decided to rise to make our votes heard,” said Ms. Lemin.

So, what went wrong?

Were the horrors too extreme, the theme is too loosely gloomy or just too uncomfortable to think?

Why, when the whole world knows the name of Dominic and Giseel Pelicot, has a lawsuit with much greater victims – victims of children who abused the nasal medical institution – went by what feels a little more than a collective shiver?

Miguel Medina/AFP

Miguel Medina/AFPWhy the world does not know the name Joel Le Skarnek?

“The case Le Scouarnec does not mobilize a lot of people. Perhaps the number of victims. We hear disappointment, lack of broad mobilization that is sorry,” said Maele Nori with a feminist non -governmental organization All of us (All of us).

Some observers reflected on the absence in this case the only, totemic figure, like Gisel Pelicot, whose social courage caught public imagination and allowed people to find light in otherwise gloomy history.

Others came to more devastating conclusions.

“The problem is that this lawsuit is a sexual cruel treatment of children.

Have a virtual silence On this topic worldwide, but especially in France. “We just don’t want to admit it,” Miriam Good-Benein told me, a lawyer who presents several victims of Le Scooarneck.

In her final arguments in court, Ms Gude-Benein condemned what she called the “systematic, silence” of France regarding the cruelty of children.

She spoke about the patriarchal society in which men who respected such positions, such as medicine, remained almost outside the reproach and indicated “the silence of those who looked the other way and those who could have arisen.”

Gets the image

Gets the imageThe laxity, which is subjected to the trial, was strange – too much for many stomachs.

The court in the bathroom in painful details heard the 74 -year -old le -arnek, 74 -year -old, launched to pedophilia, thoroughly talked about the rape of the child in a number of black notebooks, often in love with their vulnerable young patients while they were under drug.

The court also told about the growing isolation of the retired and that his lawyer called “your descent to hell”, in the last decade before he was caught, in 2017, after the abuse of a six -year -old daughter.

After all, alone in a dirty house, drunk and leaning around many relatives, Le Skuarnek spent most of his time, watching the rigid images of children on the Internet and an obsessed doll doll collection.

“I was emotionally attached to them … They did what I wanted,” Le Skuarnek said in court in his quiet monoton.

Damien Meyer/AFP

Damien Meyer/AFPIn several quarters from the court building, in the adapted civilian hall, journalists watched the deployment unfolded on the television screen. In the last days, the seat has begun to fill, and the coverage of the trial increased when it moves to the end.

Many commentators note how the lawsuit Le Scouarnec, like the Pelicot case, has exposed deep institutional failures that allowed the surgeon to continue rape long after they could be discovered and stopped.

Dominic Pelicot was caught “raising” in the supermarket in 2010, and its DNA was quickly connected with an attempt to rape in 1999 – the fact that, surprisingly, did not comply throughout the decade.

At the court of Le Scouarnec, a sequence of medical officials is ashamed, others independently overwhelmed the countryside health care system over the years to ignore the fact that the FBI was reported in America after using a credit card to download video rapes.

“I was advised not to talk about such and such a person,” said one doctor who tried to make anxiety.

“There is a lack of surgeons, and those who have appeared are welcome as the Messiah,” the hospital director explained.

“I confused, I admit, like the whole hierarchy,” another administrator finally confessed.

Another relationship between Pelicot and Le Scouarnec cases is that they both revealed about our understanding – or the lack of understanding – injury.

Without warning and support, Giselle Pelicot sharply encountered the police with a video recording of his own addiction and rape.

Later, during the trial, some lawyers and other commentators sought to minimize the suffering, indicating that it was unconscious during rape – as if the injury exists only as a wound when his scar is visible with his bare eye.

In the case of Le Scouarnec, the French police appears to have gone in search of many pedophile victims in the same form, causing people to an unexplained interview, and then informing them from blue that they were listed in the surgeon’s notebooks.

The reactions of many victims of Le Scouarnec were very different. Some just decided not to interact with the test, or with childhood they have no memory.

For others, the news of the abuse affected them deeply.

“You came into my mind, it destroys me. I have become another person – I do not admit,” the victim said, referring to Leirnek in court.

“I have no memories and I am already damaged,” the other said.

“It turned me upside down,” the policeman admitted.

And here there is another group of people who – not unlike Gizel Pelicot – found that knowledge of their abuse is a discovery that allows them to comprehend things that they did not understand about themselves and their lives before.

Some have linked their childhood with a common sense of misfortune, bad behavior or failure in life.

For other links, it was much more specific, helping to explain the litany of mysterious symptoms and behavior: from fear of intimacy to repeated genital infections and nutrition disorders.

“With my guy, every time we have sex, I get sick,” one woman in court revealed.

Gets the image

Gets the image“I had so many consequences from my operation. But no one could explain why I had such an irrational fear of hospitals,” said another victim of Amelie.

Some described that this court was similar to a group therapy session, and the victims contacted the general injuries they had previously believed to suffer alone.

“This test is similar to the clinical laboratory involving 300 victims. I sincerely hope it will change France. In any case, it will change the perception of the victim of trauma and traumatic memory,” said the lawyer Mrs. Gude-Benyang.

Despite the concern of the lack of public interests, Manan Lemuin said that the trial helped the victims “restore itself, turn the page. We posted our pain and our experience, and we leave it behind (in the courtroom). So, for me, it was released.”

Confessing his crimes, Le Skarnek will inevitably get the verdict of the guilty and will almost certainly remain in prison for the rest of his life.

Two of his sacrifices took his own life a few years before the trial – the fact he recognized in court with the same repentance but formulating he offered everyone else.

Meanwhile, some activists hope that the case will be a turning point in French society.

“Compared to the Pelicot test … We see that we don’t talk much about Le Scouarnec. We must unite. We must do this, otherwise nothing will happen, and the LE Scouarnec lawsuit will serve no purpose. I was also a victim.

A more wary assessment came from a lawyer, Mrs. Gude-Benein.

“Now there is a very important confrontation between those who want to convey sexual violence to children, and those who want to cover it, and this confrontation is happening today in this lawsuit. Who will win?” She thought.

If you have influenced any questions raised in this story, information and support can be found in Line of action BBC.