Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Musical correspondent

Gets the image

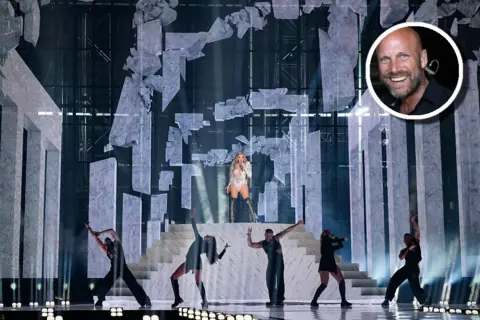

Gets the imageThirty -five seconds. Here you can constantly change the Eurovision set.

Thirty -five seconds to bring one set of performers out of the stage and put the following in the right place.

Thirty -five seconds to make sure everyone has the right microphones and headphones.

Thirty -five seconds to make sure the props are in place and tightly secured.

While you are at home watching the introductory videos, known as postcards, dozens of people suggest the scene by setting the scene for what is next.

“We call it a change in tire formula 1,” says Richard van Ruhandaal, a supportive leader of the Dutch stage who makes it work.

“Everyone in the crew can only make one. You run on stage with one light bulb or one subscription.

“It’s a little like skating.”

The crew of the scene begins to rehearse its “tire f1” a few weeks before the competition participants even arrived.

Each country sends detailed plans for its production, and Eurovision is hired to play in action (in Liverpool 2023, it was students from the local school art school), and stacks begins to shave valuable seconds with change.

“We have about two weeks,” says Van Ruhandaal, who is usually in Utrecht, but is in Basel for this year.

“My company has about 13 Dutch and 30 local guys and girls who sway in Switzerland.

“During these two weeks I have to find out who is suitable for every job. Someone is good in running, someone’s good in lifting, someone’s good in the body.

As soon as the song ends, the team is ready for rolling.

And also on the stages, there are people responsible for the positioning of the lights and the installation of pyrotechnics; and 10 cleaners that sweep the stage with mop and vacuum cleaners between each performance.

“My cleaners are as important as the stage crew. You need a clean scene for the dancers – but also if there are overhead shots of anyone who lay, you don’t want to see on the sheeprints floor.”

Attention to detail is clinical. Behind the scenes, each performer has his own microphone stand, set to the right height and angle to make sure that each performance is perfect for cameras.

“Sometimes the delegation will say that the artist wants to wear other shoes for the big finale,” says Van Rouvendaal. “But if it happens, the microphone is at the wrong height, so we have a problem!”

SRG / SSR

SRG / SSRThe spontaneous change of shoes is not the worst problem he encountered. At the 2022 competition in Turin the scene was 10 million (33 feet) higher than in the scenes.

As a result, they pushed strong details – including a mechanical bull – up the steep ramp between each act.

“We were exhausted every night,” he recalls. “This year is better. We even have an extra tent behind the scenes where we prepare props.”

Gets the image

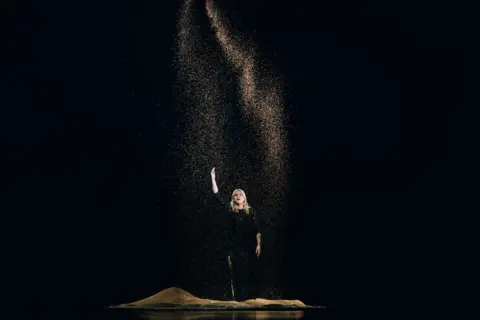

Gets the imageThe props is a huge part of the Eurovision. The tradition began at the second competition in 1957, when Marga Germany Marga Heels sang part of his song Phone, phone in (you already guessed) the phone.

For decades, the production has become more and more perfect. In 2014, Ukraine Maria Yaremchuk trapped one of her dancers in giant hamsters, while Romania brought a literal gun to her performance in 2017.

This year we have a disk -scales, space bunkers, a magical food blender, a Swedish sauna and, for the UK, the chandelier died.

“In fact, these are great logistics efforts to get all the details,” says Domaris Reist, deputy head of the production this year.

“All this is organized in a circle.

“Behind the scenes, the requisites used, are pushing back to the back of the queue, and so on. It’s all in the planning.”

During the show there are several secret passes and “smuggling” to get props in vision and out of vision, especially when the performance requires new elements halfway.

Drop your mind if you like, at Sam Ryder’s performance for the UK at the 2022 competition in Italy.

There he was, one on the stage, knocked out the notes of Falseta in his sharp overalls, when suddenly an electric guitar appeared from the air and landed in his hands.

And guess who put it? Richard Van Ringndaal.

“I’m a magician,” he laughs. “No, no, no … It was a cooperation between the camera director, the British delegation and the crew of the stage.”

In other words, Richard clung to the stage, the guitar in his hand, while the director raised a wide shot, hiding his presence from the audience at home.

“It is choreographed to the nearest millimeter,” he says. “We are invisible, but we must be invisible.”

Reuters

ReutersWhat if everything goes wrong?

There are certain tricks that viewers never notice, Van Rouwendaal Reveeals.

When it announces the “stage is not clear” in the headset, the director can buy time, showing a long shot of the audience.

In the case of a larger incident – “the camera can break through, support can fall” – they cut to the presenter in the green room, which can fill a couple of minutes.

In the dispatching ribbon, which pursues a rehearsal, he plays in sync with a live show, which allows the director to go to pre -recorded footage in the case of something like a stage invasion or incorrect microphone.

However, the visual failure is not enough to back up the back-like tape-like Zoya Zoe May found in the first semifinals on Tuesday.

Her performance was briefly interrupted when the filing on stage was frozen, but the manufacturers simply cut to a wide shot until it was fixed. (If it happened in the finals, she would have been offered the opportunity to perform again.)

“In fact, there are a lot of measures taken to make sure that every act can be shown in the best way,” says Raist.

“There are people who know the rules by heart that they played through what could happen and what we would do in different situations.

“I will sit next to the manager of production, and if there is (the situation) if someone needs to run, perhaps it will be me!”

Sarah Louise which

Sarah Louise which Sarah Louise Bennett

Sarah Louise BennettIt is not surprising to find out that the production of a live three -hour broadcast with thousands of moving parts is incredibly tense.

This year, the organizers imposed measures to protect the well -being of the contestants and crew, including the rehearsal of closed doors, longer breaks between the show and the creation of the “disabled area” where the cameras are banned.

However, the raist says she has worked every weekend over the last two months, while Van Ruwandaal and his team regularly pull 20-hour days.

The changes are so long that back in 2008, the legend for the production of Eurovision Ola Melzig built a bunker under the stage, complete with the sofa, “unfortunately insufficiently used” PS3 and two (yes, two) espresso machines.

“I don’t have hidden luxury like ola. I’m not yet at this level!” Laughs Van Ruwandaal

“But behind the scenes, I have a place with my crew. We have Stroopwafels, and last week it was King’s Day in Holland, so I baked pancakes for everyone.

“I try to make it fun. Sometimes we go out and drink and cheerfully because we had a great day.

“Yes, we must be on top and we must be sharp as a knife, but together fun is also very important.”

And if everything goes according to the plan, you will not see them this weekend.