Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC World Service

Phil subscriber

Phil subscriberLocated in the mountains of Iraq Kurdistan, sitting in the picturesque village of Sergele.

During the generations of the village, grenades, almonds and peaches and harvesting in the surrounding forests for wild fruits and spices were earning a living.

But Sergel, located 16 km (10 miles) from the border with Turkey, is increasingly surrounded by Turkish military bases that are scattered on the slopes.

One, which was sitting halfway along the western ridge, emerges over the village and the other in the east is being built.

In the last two years, at least seven have been built, including one small dam that regulates Sergeel’s water supply, which makes it on the borders of the villagers.

“This is a 100% form of occupation of the Kurdish (Iraqi Kurdistan) land,” says Shergel Shergel’s farmer, 50 years who lost access to some of his land.

“The Turks ruined it.”

Phil subscriber

Phil subscriberSergeel now threatens to be involved in the fact that it is known locally as a “prohibited zone” – a large strip of land in northern Iraq, affected by the Turkey war with the Kurdish Militia Group PKK, which launched an uprising in South Turkey in 1984.

The forbidden zone covers virtually the entire length of the Iraq border with Turkey and places up to 40 km (25 miles).

The teams of peacekeepers engaged in human rights defenders based in Iraq Kurdistan, saying that hundreds of civilians were killed by drones and air strikes in and around the prohibited area. According to the report of the Kurdistan Parliament in 2020, thousands were forced from their land, and whole villages were empty.

Now Sergeel is effectively on the Turkish War line with the PCC.

When the BBC World Service Eye visited the area, the Turkish plane knocked the mountains that surrounded the village to eradicate the PCC militants that had long acted from caves and tunnels in northern Iraq.

Most of the land around Sergel was burned.

“The greater the reason they put, the worse it becomes for us,” Sherwan says.

In recent years, Turkey has rapidly growing its military presence in the prohibited zone, but so far the scale of this expansion has not been publicly available.

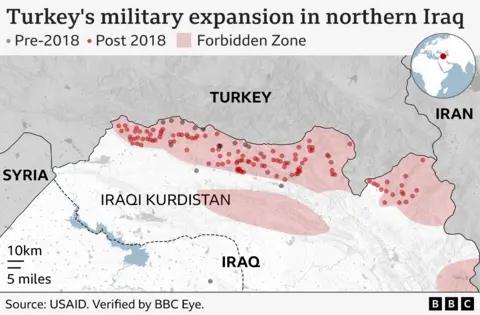

Using satellite images, evaluated by experts and confirmed on the ground reporting and open source, BBC found that as of December 2024, the Turkish military built at least 136 fixed military units in northern Iraq.

Turkey now conducts defect-control over more than 2000 km (772 square miles) of Iraqi land in its huge network of military bases.

Satellite images also indicate that the Turkish military has built at least 660 km (410 miles) roads that connect their facilities. These food routes led to the deforestation and left a long imprint on the mountains of the region.

While several bases dated the 1990s, 89% were built since 2018, after which Turkey began to significantly expand its military presence in Iraq Kurdistan.

The Turkish government did not respond to the BBC requests for an interview, but claimed that its military bases were necessary for the PCC to repel, which was intended for the terrorist organization Ankara and several Western countries, including the UK.

Phil subscriber

Phil subscriberThe capital of the horse, which is only 4 km (2.5 miles) from the Iraq border, and parts of which are in the prohibited area, may offer an idea of Sergeel.

Once upon a time, it was famous for its Apple production, now few residents remain here.

Farmer Salad Said, whose land is in the shadow of a large Turkish base, has not been able to grow his vineyard for the last three years.

“At the moment when you come here, you will have an unmanned guidance over you,” he says BBC.

“They shoot you when you stay.”

The Turkish military for the first time created here in the 1990s and have since consolidated their presence.

Its main military base, which presents concrete explosions, towers and communications and place for armored personnel carriers, are much more developed than smaller outposts around Sergel.

Salam, like some other locals, believes that Turkey ultimately wants to claim the territory as their own.

“Everything they want is we leave these areas,” he adds.

Phil subscriber

Phil subscriberNext to the horse mass, the BBC saw the Turkish forces effectively pushed the Iraqi border guards responsible for the protection of the international Iraqi borders.

In several places, the border guards were well engaged in positions on the territory of Iraq, directly opposite the Turkish troops, unable to approach the border and potentially risk the collision.

“The messages you see are Turkish positions,” says General Farhad Mahmoud, pointing to the ridge a little through the valley, about 10 km (6 miles) in Iraq.

But “we can’t reach the limit to find out about the number of messages,” he adds.

The military expansion of Turkey in Iraqi Kurdistan – is fueled by growth as a drone and a growing defense budget – it is considered as part of a wider shift of foreign policy for greater intervention in the region.

Like its activity in Iraq, Turkey also sought to create a buffer zone along its border with Syria to hold Syrian armed groups, allies from the PCC.

In public, the Iraqi government condemned Turkey’s military presence in the country. But behind closed doors, he set some demands of Ankara.

In 2024, both sides signed a memorandum of understanding to fight the PCC.

But the document received by the BBC did not contain any restrictions on Turkish troops in Iraq.

Iraq depends on Turkey for trade, investment and water safety, while its destroyed domestic policy has further undermined the government’s ability to take a strong position.

Iraq’s National Government did not respond to BBC requests for comment.

Meanwhile, the rulers of the semi-autonomous region of Iraq Kurdistan have a close connection with Ankara based on mutual interests and often harm the civilian population due to the military actions of Turkey.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the Archish Enemy of the PCC, is dominated by Kurdistan’s regional government (KRG) and has been officially responding since 2005, when the Iraqi Constitution has given its semi -automatic status.

KDP’s close ties with Turkey contributed to the region’s economic success and strengthened their position, both against its regional political competitors and the Iraqi government in Baghdad, with which it came up with more autonomy.

Hoshiaar Zabari, a senior member of the Political Bureau of the KDP, sought to blame the PCC in the presence of Turkey in Iraqi Kurdistan.

“They (the Turkish military) do not hurt our people,” he said to the BBC.

“They do not detain them. They do not interfere with their work. Their focus is on their sole purpose.”

Phil subscriber

Phil subscriberThe conflict shows no signs of ending, despite the long ascending PCC leader Abdullah Ocolon, who calls in February to put his hands and dissolve his fighters.

Turkey continued to idolize the goals in Iraqi Kurdistan, while PKK claimed responsibility for the Turkish drone last month.

Although violent incidents in Turkey have fallen since 2016, according to the results of the NGO crisis group, those who are in Iraq have emerged, and civilians living in the border region face the rise in death and movement.

One of the killed was 24-year-old Alan Ismail, a fourth cancer patients who suffered from an air strike in August 2023 while traveling to the mountains with his cousin Hashem.

On this day, the Turkish military denied the strike, but the BBC police report attributed the incident to the Turkish drone.

When Hashem filed a complaint to the local court on the attack, he was detained by Kurdish security forces and held eight months on suspicion of supporting a PCC – the accusation he and his family are denying.

“It destroyed us. It’s like killing the whole family,” says Ismail Chichu, Alan’s father.

“They (Turks) have no rights to kill people in their country on their land.”

The Turkish Ministry of Defense did not respond to the BBC’s requests for comment. He previously told the media that the Turkish Language Armed Forces adhere to international law, and that when planning and fulfilling their activities, they only focus on terrorists, while taking care to prevent civilians.

Phil subscriber

Phil subscriberThe BBC saw documents that believe that the Kurdish authorities may have acted to help Turkey avoid responsibility for civil losses.

Confidential documents noticed by the BBC show that the Kurdish court closed the investigation into Alan’s killings, saying the criminal was unknown.

And his death certificate – issued by the Kurdish authorities and saw the BBC – says he died from “explosive fragments”.

Without mentioning when the victims of air strikes died as a result of violence rather than the accident, it burns families to seek justice and compensation, to which they are entitled to both Iraqi and Kurdish legislation.

“In most death certificates, they wrote only” Infijar “, which means an explosion,” says Kamaran Otman of the teams of peacekeepers.

“It can be anything.

“I think the Kurdish regional government does not want Turkey to be responsible for what they are doing here.”

The KRG said he acknowledged “the tragic loss of civilian population as a result of the military confrontation between the PCC and the Turkish army in the region.”

It adds that “a number of victims” was recorded as “civil martyrs”, that is, they were unfairly killed and giving them the right to compensate.

Almost two years after Alan was killed, his family is still waiting for, if not compensation, at least for recognition of the CRG.

“They could at least send their condolences – we do not need their compensation,” Ismail says.

“When something disappears, it disappeared forever.”