Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Climate and scientific reporter

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin ChurchAt the top of the pure rocks, Santorini is the world-famous tourist industry worth millions. Beneath it is the risk of the omnipotent explosion.

A huge ancient eruption created a dreamy Greek island, leaving a wide crater and a horse -shaped rim.

Now scientists are investigating for the first time how dangerous may be the next big.

BBC News spent a day aboard the British royal scientific ship when they were looking for clues.

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin ChurchA few weeks before, almost half of the 11,000 Santorini residents fled to security when the island closed in a number of earthquakes.

It was a sharp reminder that under the idyllic white villages, scattered by Gair Restaurants, hot baths in rental Airbnb, and vineyards on rich volcanic soil, two tectonic plates are grinding in the crust.

Professor Isabel Yie, an expert on very dangerous underwater underwater volcanoes with the National Oceanographic Center, leads the mission. About two -thirds of world volcanoes are under water, but they are unlikely to be controlled.

“It’s a bit like” out of sight, in terms of understanding their danger, compared to better -known ones, such as Vesuvius, “she says on the deck when we see two engineers who consider the robot from the car from the ship.

This work, which will come so soon after the earthquakes, will help scientists understand what type of seismic unrest may indicate the eruption of the volcano inevitable.

The last eruption of Santorini occurred in 1950, but recently in 2012 there was a “period of excitement”, says Isabel. Magma flows into the volcano cell, and the islands are “swollen”.

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin Church“Underwater volcanoes are capable of truly large, truly devastating eruptions,” she says.

“We have fallen into a sense of false security when you are used to small eruptions and a volcano that is safe. You think the same will be the same – but it can’t,” she says.

In 2022, the eruption of Hunga Tunga in the Pacific created the largest underwater explosion, which, if -was recorded, and created a tsunami in the Atlantic with Shak’s Waves in the UK. Some islands in the tone, near the volcano, were so devastated that their people never returned.

Under our feet on the ship, 300 m (984 feet) down, there are hot holes. These cracks in the ground turn the sea bottom into a vividly -charging world of the protruding rocks and gas clouds.

“We know more about the surface of some planets than what is below,” Isabel says.

The robot descends to the seabed to collect liquids, gases and reject the rocks.

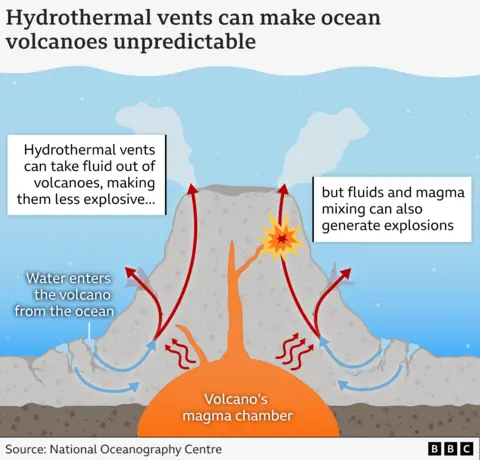

These ventilation holes are hydrothermal, that is, hot water is poured from cracks, and they often form near the volcanoes.

That is why Isabel and 22 scientists from all over the world have been on this ship for a month.

So far, no one has been able to work out when the volcano becomes more or less explosive when the sea water in these ventilation holes is mixed with the magma.

“We are trying to reflect the hydrothermal system,” Isabel explains. It’s not like making a map on land. “We have to look into the ground,” she says.

The opening is investigated by Santorini Calder and sails to Colombo, another major volcano in the area, about 7 km (4.3 miles) northeast of the island.

Two volcanoes are expected to not break out, but this is just a matter of time.

The expedition will create data sets and cards Geohazard for the Greek civil defense agency, explains Prof. Paraskevich Nomika, a member of the government emergency group that met daily during the crisis of the earthquake.

She has grown from Santorini, hearing about past earthquakes and eruptions from her grandfather. The volcano inspired her to become a geologist.

“This study is very important because it informs the locals how active volcanoes are, and it will reflect the area that will be forbidden to access during the eruption,” she says.

This will reveal which parts of the sea floor Santorini are the most dangerous, she adds.

These missions are incredibly expensive, so ISOBEL kills in experiments at night and on the day when scientists work in 12-hour shifts.

John Jamison, Professor of the Canadian Memorial University in Newfoundland, shows us volcanic rocks removed from the ventilation holes.

“Don’t choose this,” he warns. “He’s full of arsenic.”

Pointing to another who looks like a black and orange meringue with gold dust, he explains: “This is a real secret – we don’t even know what it is done.”

These breeds tell about the history of fluid, temperature and material inside the volcano. “This is a geological environment that is different from most others – it’s really interesting,” he says.

But the heart rate of the mission is a dark cargo container on the deck, where four people look at the screens mounted on the wall.

Using a joystick that will not look out of the place on the gaming console, two engineers control the underwater robot. Isabel and Paraskevich trades the theories that there is in the fluid pool found by the robot.

They recorded very small earthquakes around the volcano caused by fluid moving on the system and causing fractures. ISOBEL plays us audio recording. It sounds like a bass in a nightclub that rises up and down.

They detect how the liquid moves along the rocks, throbbing the electromagnetic field into the ground.

This creates a 3D card that shows how the hydrothermal system connects to the magic volcano chamber, where the eruption is erupted.

“We do science for people, not scientists for scientists. We are here for people to feel safe,” Paraskevich says.

The recent crisis of the earthquake in Santorini emphasized how exposed the island’s residents to seismic threats and how much they depend on tourism.

Returning to the dry land, photographer Eve Randle meets me in his favorite place for wedding shoots. When the so -called Roy of earthquakes got in February, she left the island with her daughter.

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin Church“It was really scary because it is increasingly intense,” she says.

Now she is back, but the business is slower. “People canceled the order. I usually start shooting in April, but my first job is until May,” Eve says.

On the main square of the supermarket Santorini British-Canadian tourist Janet tells us six out of 10 of 10 of 10 canceled the holiday.

She believes that more accurate scientific information about the likelihood of earthquakes and volcanoes will help others feel more calm in visiting.

“I get Google notifications, I receive scientists’ notifications and it helps me feel safe,” she said.

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin ChurchBut Santorini will always be a dream place. In Imerovigli we see two people climb the curved roofs to get the perfect shot.

The couple – married in 15 minutes – traveled from Latvia and was not delayed from the underwater risks of the island.

“In fact, we wanted to marry the volcano,” says Tom, his bride Christina nearby.

Additional Tom Ingem and Kevin Church Report, Climate and Scientific Team