Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC Afghan Service, Kabul

BBC

BBCAmin will never forget her childhood. She was only 12 years old when she was told that she could no longer go to school as boys.

The new academic year began on Saturday in Afghanistan, but the fourth year in a row girls older than 12 were forbidden to attend classes.

“All my dreams were broken,” she says, the voice is gentle and filled with emotions.

Amin, who is now 15 years old, always wanted to become a doctor. Like a little girl, she suffered from heart defect and suffered surgery. The surgeon who saved her life was a woman – the image left with her and inspired her to take her study seriously.

But in 2021, when the Taliban repeated power in Afghanistan, Amina’s dream stopped sharply.

“When my dad told me that the schools were closed, I was very sad. It was a very bad feeling,” she says quietly. “I wanted to get an education so I could become a doctor.”

Limiting for adolescent girls imposed by the Taliban has affected more than a million girls, UNICEF, UN Children’s Agency reports.

Now Madrassas – religious centers focused on Islamic exercises – have become the only way for many women and girls -adolescents. However, those whose families can afford private learning can still have access to subjects, including math, science and languages.

While Madrassas are regarded as a way to offer young women access to some educational education they would have in major schools, others say they do not replace and have problems with brainwashing.

I meet with Amina in the dim-lit al-Khadit basement in Kabul, a recently created private religious training center for about 280 students of different ages.

The basement is cold, with cardboard walls and sharp colds in the air. After the chat is about 10 minutes, our feet were already numb.

Al-Khodit Madars was founded by the year ago, Brother Amin Hamid, who felt forced to act after he saw that the ban on her education took her.

“When the girls were denied education, my sister’s dream of becoming a heartfelt surgeon was crushed, which greatly influenced her well -being,” says Hamid, who in the early thirties.

“Having the opportunity to return to school, as well as study the midwife and first aid, made her feel much better in her future,” he adds.

Afghanistan remains the only country where women and girls are prohibited from secondary and higher education.

Initially, the Taliban government suggested that the ban would be temporary before fulfilling certain conditions, such as the “Islamic” curriculum. However, there was no progress against re -opening schools for older girls in these years.

In January 2025, the report of the Afghanistan Center for Human Rights assumed that Madresas used the Taliban to achieve ideological goals.

The report states that “extremist content” was integrated into their curriculum.

It states that the textbooks that act as the Taliban promote their political and military activities and prohibit the mixing of men and women, as well as approving the wearing of the hijab.

The Afghan Human Rights Center causes a ban on senior girls who attend the school “systematic and purposeful violation” the right to quality education.

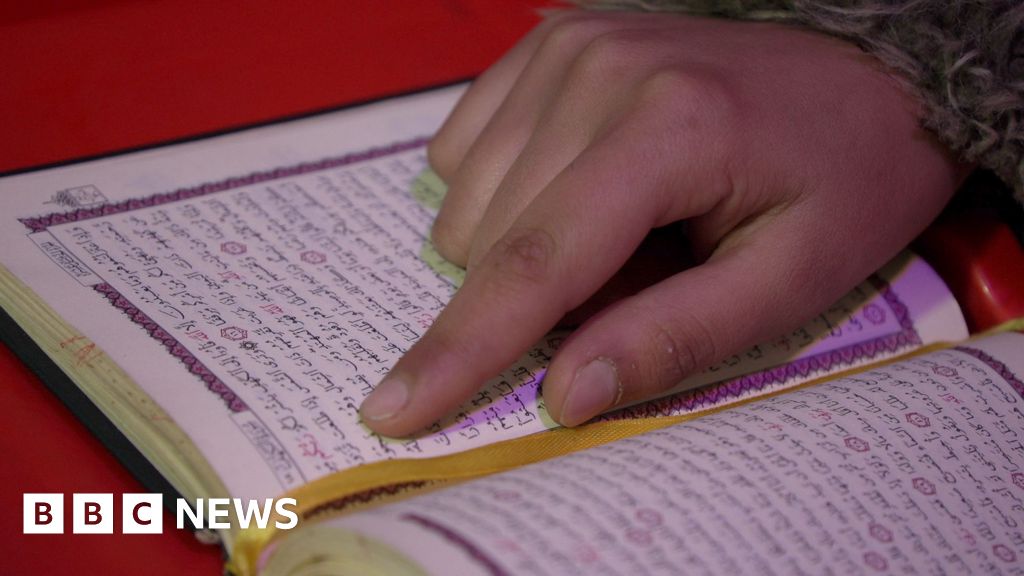

Prior to the Taliban return, the number of registered medress is believed to be about 5,000. They focus on religious education, which includes Kuran, Hadis, Sharia and Arabic Law.

But since the girls’ education restrictions were imposed, some have expanded the teaching of subjects, including chemistry, physics, mathematics and geography, as well as languages such as gifts, post and English.

Despite the fact that last December last December last December last December last December last December last December last December last December last December last year last December last year.

Hamid said he was devoted to the provision of education that combines both religious and other academic subjects for high school girls.

“Socialization with other girls again made my sister much happier,” he told me with a smile, clearly proud of his sister.

We visit another regardless of Madras in Kabul.

Sheikh Abdul Kadr Gilani Madras raises more than 1,800 girls and women aged five to 45 years. Classes are organized by students’ abilities, not age. We were able to visit strict supervision.

Like the al-Jadeth-Madros, it freezes cold. There is no heating in the three -story building, and in some classes there were no door and windows.

In one large room, two classes of the Quran and the sewing class are held at the same time when a group of girls in hijab and black face masks are sitting on the carpet.

The only source of heat at the school is a small electric radiator in the office of the director of the second floor of Mohammad Ibrahim Baraga.

Mr. Baraksham tells me that academic subjects are taught with religious.

But when I ask for evidence of this, employees are looking for a while before you bring out a few broken mathematics and science textbooks.

Meanwhile, classes are well staffed with religious texts.

This Madrace is divided into two sections: formal and informal.

The official section covers subjects such as languages, history, science and Islamic studies. The informal section covers chicken studies, Hadys, Islamic law and practical skills such as tailoring.

In particular, the graduates of the informal section exceed those who from the official section by 10 to one.

Hadia, who has recently graduated from Madrassa after studying a wide range of subjects, including math, physics, chemistry and geography.

She speaks hotly about chemistry and physics. “I love science. It’s all about matter and how these concepts treat the outside world,” she says.

Now Hadia teaches the Quran in Madras, because she tells me that there is not enough demand for her favorite items.

Safia, also 20, teaches the Pushto language in al-Khadrit Madros. She passionately believes that girls in religious centers should strengthen what she called her personal development.

It focuses on FIQH, the Islamic Legal Base necessary for daily Muslim practices.

“FiCH is not included in major schools or universities. Like a Muslim woman, studying FIQH is vital to improve women,” she says.

“Understanding concepts such as Ghusl – leaching – differences in the portion between the sexes and the prerequisites of prayer are crucial.”

However, it adds that Madrassas “cannot serve as a replacement for basic schools and universities.”

“Educational institutions, including major schools and universities, are absolutely important for our society. Closing these institutions will lead to a gradual reduction in Afghanistan,” she warns.

13 -year -old pussy is a quiet, restrained student who is also studying at Shaih Abdul shot of Jilani Madras. From a pious family she attended classes with her older sister.

“Religious subjects are my favorite,” she says. “I like to find out what kind of hijab should carry a woman as she should treat her family, how well she treats her brother and husband and never be rude to them.”

“I want to become a religious missionary and share my faith with people around the world.”

UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Afghanistan Richard Bennett has caused serious concern over the Madras -style restrictive education system.

He emphasized the need to restore educational opportunities for the sixth grade girls and for women in higher education.

Mr. Bennett warned that this limited education combined with high unemployment and poverty “could promote radical ideology and increase the risk of homegrown, threatening regional and global stability.”

The Taliban Ministry of Education claims that about three million students in Afghanistan are studying at these religious educational centers.

He promised to restore the schools of girls under certain conditions, but that has not yet come true.

Despite all the problems faced by Amin – its struggle for health and the ban on education – it remains hopeful.

“I still believe that one day the Taliban will allow schools and universities to resume,” she says with conviction. “And I will understand my dream of becoming a heartfelt surgeon.”