Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC’s eye studies

BBC

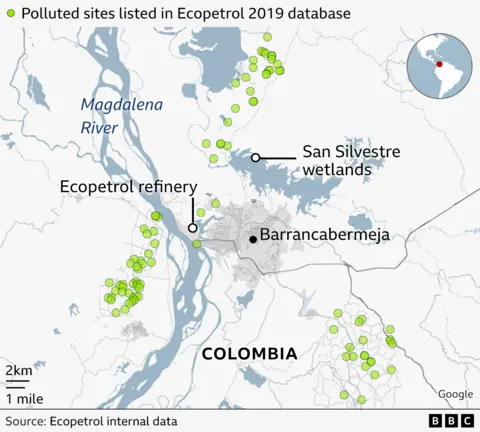

BBCThe Colombian Energy Giant Ecopetrol has polluted hundreds of oil sites, including water sources and swampy biodiversity sites.

The data that is traced by the former employees shows more than 800 records of these sites from 1989 to 2018 and shows that the company has not reported a fifth.

The BBC has also received figures that show that the company has been shedding oil hundreds of times since then.

Ecopetrol says it is fully in line with Colombian legislation and has a stability practice leading in the industry.

The company’s main refinery is in Barrancabermeja, 260 km (162 miles) north of the Colombian capital Bogot.

A huge accumulation of planting plants, industrial chimneys and storage tanks lasts up to 2 km (1.2 miles) along the shores of the longest Colombia river, Magdalen is a source of water for millions.

Yuly velásquez

Yuly velásquezMembers of the fishing community believe that oil pollution affects wildlife in the river.

In the wider area live endangered turtles, manators and spider monkeys, and is included in the species rich in hot spots in one of the most biodiversity countries in the world. The nearby wetlands include a safety habitat for jaguars.

When the BBC visited last June, families were fishing in waterways crossed with oil pipelines.

One of the local said that some of the fish they caught liberated the spicy smell of crude oil when cooked.

In places on the surface of the water you can see the film with the overflowing curls – a distinctive signature of oil pollution.

The fisherman plunged into the water and lifted a lump of vegetation saturated with dark mucus.

Speaking to this, Julia Velas, the president of the Fisherman’s Federation in the region, said: “This is all fat and waste that comes directly from the Ecopetrol oil refinery.”

Ecopetrol, which is 88%owned by the Colombian state and is made to the New York Stock Exchange, reject the fishermen’s statements that it pollutes the water.

In response to the BBC questions, it states that it has effective sewage treatment systems and effective emergencies for oil spilling.

Andres Olart, a human rights activist who shared the company’s data, says that the pollution is dating for many years.

He joined Ecopetrol in 2017 and started working as a CEO. He says he soon realized that “something was wrong.”

Mr. Olart says that he challenged the executives that he characterized as “terrible” pollution data, but there was an eahyd room for reactions such as: “Why are you asking these questions? You don’t get what it comes.”

He left the company in 2019 and shared a large number of companies with the US Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) and then with BBC. BBC confirmed that he came from the Ecopetrol servers.

One of the databases he shared since January 2019 contains a list of 839 so -called “unresolved environmental impacts” across Colombia.

Ecopetrol uses this term to mean areas where oil is not completely cleaned of soil and water. The data shows that since 2019, some of these sites remained contaminated in this way for more than ten years.

Mr. Olart claims that the firm tried to hide some of their Colombian authorities, pointing about a fifth of the records, with the inscription “Only known Ecopetrol”.

“You could see the category in Excel, where he lists, what is hidden from power, and which is not, which shows the process to hide things from the government,” says Mr. Olart.

The BBC was shot on one of the sites marked only by the famous ecopetrol, which was dated 2017 in the database. Seven years later, thick, black, greasy in the appearance of a substance with plastic barriers on the maintenance around it was visible along the edge of the swamps.

Ecopetrol CEO from 2017 to 2023 Felip Bayon told the BBC that he strongly denied the proposals that there was some policy to contain contamination information.

“I tell you with the full confidence that there was no, and there was no policy or the instructions that say,” Such things cannot be shared, “he said.

Mr. Bayon accused the sabotage of many oil spills.

Colombia has a long history of armed conflicts, and illegal armed groups are aimed at oil premises – but “theft” or “attack” are mentioned only for 6% of the cases listed in the database.

He also said he believed that there has been a “significant progress” since then in solving the problems that lead to oil pollution.

However, a separate data set indicates that Ecopetrol continues to be polluted.

The figures received by the BBC from the Environmental Regulator of Colombia, the National Environmental Protection (Anla), indicate that Ecopetrol reports hundreds of oil studs in the year since 2020.

Asked about the database of contaminated sites 2019, Ecopetrol admits that it has 839 incidents in the environment, but the disputes that they were all classified as “unresolved”.

The firm says 95% of contaminated sites that have been classified as unresolved since 2018 have been cleaned.

It states that all contaminants are subjected to the control process and reported by the regulator.

The regulator data includes hundreds of spill in the Barrankabermey area where Ms Velazquez and fishermen live.

Fishermen and her colleagues monitored biodiversity in the wetlands entering the Magdalen River.

She said that there was a “massacre” about the fauna. “There were three dead, five dead buffaloes this year. We found more than 10 Kayman. We found turtles, capibers, birds, thousands of dead fish,” she said in June last year.

It is unclear what caused death – the weather phenomenon of the El -Ninho and the climate change can be factors.

The study in 2022, the University of Nottingema, lists oil pollution – from oil production and other industrial and domestic sources – as one of the factors among several, including climate change that worsen the Magdalen River.

Mr. Olart left Ecopetrol in 2019. He moved to his family house near Barrancabermeja, and says he met with old contacts to ask about work. He soon says that an anonymous subscriber called the phone, threatening to kill him.

“I realized in the call that I thought I had filed complaints about Ecopetrol,” he says.

Mr. Olart says there is more threats, including the note he showed in the BBC. He does not know who made threats and there is no evidence that Ecopetrol ordered them.

Ms. Velajes and seven other people also reported the BBC that they were threatened with death after ecopetrol.

She said the armed group released a warning in her home and sprayed the word “leave” on the wall.

Now the fishing woman is protected by armed guards paid by the government, but the threats are ongoing.

Asked about the threats described by Mr. Olart, the former CEO of Mr. Bayon said they were “absolutely unacceptable”.

“I want to do it quite understandable … that never, at any time, was no such order,” said Mr. Bayon.

Mrs. Velas and Mr. Olart know that the risks are real. Colombia is the most dangerous country in the world for environmental defenders, according to a global NGO witness, 79 were killed in 2023.

Experts say such murders are connected with decades of Colombia, in which armed conflicts in which state forces and paramilitaries associated with them fought with left -wing rebels.

Despite the government’s attempts to stop the conflict, armed groups and drug cartels remain active in some parts of the country.

Matthew Smith, the oil analyst and the financial journalist based in Colombia, says it does not believe that Ecopetrol leaders are involved in the threats of armed groups.

But he says there is a “huge” overlap between former paramilitary groups and a private security sector.

Private security firms often work with former paramilitary groups and compete for profitable oil protection contracts, he says.

Mr -n Olarte shared the ECOPETROL internal e -mail that shows that in 2018 the company paid a total of $ 65 million more than $ 2,800.

“There is always the risk of some infection between private companies, the types of people they work, and their desire to constantly maintain a contract,” says Mr. Smith.

He says it can potentially even include the abduction or murder of community leaders or environmental defenders to “ensure that Ecopetrol operations continue smoothly.”

Mr. Bayon said “convinced that checks and proper checks were made” regarding the company’s relations with private security companies.

Ecopetrol says there was never a relationship with illegal armed groups. It states that it has a strong verification process and evaluates impact on human rights for its activity.

The BBC has contacted other members of the former Ecopetrol leadership since Mr. Olart’s employment, who have strongly denied the charges in this report.

Now, living in Germany, Mr. Olart filed complaints about the ecological entry of Ecopetrol to the Colombian authorities and the company itself – so far, without significant results.

He was also in a number of legal affairs against Ecopetrol and his management related employment, which have not yet been resolved.

“I did it in defense of my house, my land, my region, my people,” he says.

Mr. Bayon emphasized the economic and social significance of the Ecopetrol Colombia.

“We have 1.5 million families who do not have energy access and coal and coal,” he said. “I believe that we should continue to rely on clean production of oil, gas, all energy sources, before the transition, without stopping the industry that is so important for Colombians.”

And Ms. Velasoza still decided to continue to talk despite threats.

“If we do not fish, we don’t eat,” she said. “When we say and inform, we kill … And if we do not inform, we kill ourselves because all these cases of severe pollution destroy the environment around us.”