Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

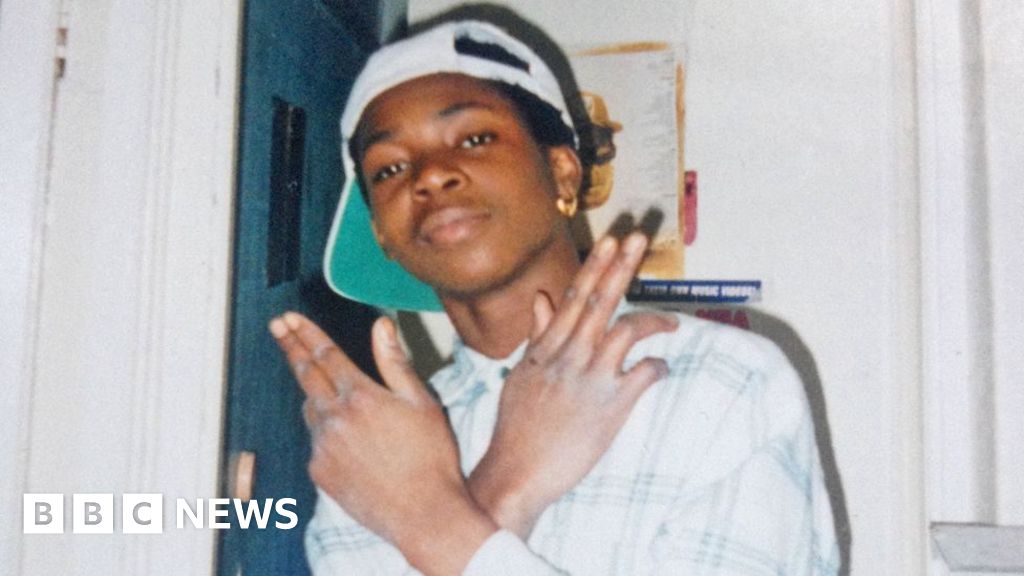

Mark Wilberfors

Mark WilberforsWhen my mother told me at the age of 16 that we were traveling from the UK to Ghana for a summer vacation, I had no reason to doubt it.

It was just a quick trip, a temporary break – there is nothing to worry about. Is that so I thought.

One month she threw a bomb – I didn’t return to London until it reformed and earned enough GCSE to continue my education.

I was extended in a similar way with the British-Hayan teenager who recently drove his parents to the Supreme Court in London to send him to school in Ghana.

In their defense, they said the judges that they did not want to see their 14-year-old son “another black teenager who had death on London Street.”

Back in the mid-1990s, the mother, an elementary school teacher, was motivated by similar problems.

I was expelled from two secondary schools in the London district of Bret, hanging out with the wrong crowd (becoming a wrong crowd) – and headed down the dangerous path.

My closest friends at the time were in prison for armed robbery. If I stayed in London, I would almost certainly be convicted with them.

But sending to Ghana also felt a prison term.

I can empathize with a teenager who stated in a court statement that he feels “living in hell.”

However, speaking of myself, as long as I turned 21, I realized that my mother had made, it was a blessing.

Unlike the boy in the center of the London court – which he lost – I did not go to the boarding school in Ghana.

My mother put me on the care of her two closest brothers, they wanted to watch me, and it was believed that staying next could be too distracted.

For the first time I stayed with Uncle Fifi, a former UN environmentalist, in a city called Dansoman, near the capital.

Changing lifestyle was severely affected. In London, I had my own bedroom, access to washing machines and independence – even when I use it recklessly.

Gets the image

Gets the imageIn Ghana, I woke up at 05:00 to sweep the yard and wash the uncle and my aunt’s car.

Later, I will steal her vehicle – something of a turning point.

I didn’t even know how to ride properly, considering the instructions as automatic, and I crashed into a Mercedes a high -ranking soldier.

I tried to leave the scene. But this soldier caught me and threatened me to take me to Burma Lger, a notorious military base where people disappeared in the past.

It was the last really ill -advised what I was doing.

I learned not only a discipline in Ghana – it was a prospect.

Ghana’s life showed me how much I took for granted.

Hand -washing clothes and cooking with my aunt made me evaluate the necessary effort.

Food, like everything in Ghana, requires patience. There was no microwave ovens.

For example, creating a traditional dough dish is painstaking and involves a knock of boiled yams or maniots in a paste with a solution.

At the time, it felt as a punishment. Looking back, it was a stability.

Initially, my uncles looked at me to place me in high-end schools such as Ghana International School or Sos Herman Gminer International College.

But they were smart. They knew I could just create a new crew to cause chaos and pranks.

Instead, I received private training at the Academy of the Apo, a state high school in which my deceased was present. This meant that I was often taught on my own or in small groups.

Salley Lans

Salley LansLessons were in English, but from school those around me often spoke local languages, and I was easy to pick them up, perhaps because it was such an exciting experience.

Returning home in London, I liked to study my mother’s language – but was far from free.

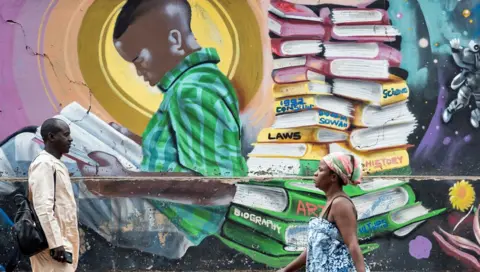

When I later moved to the city theme to stay with my favorite uncle, Uncle Jojjo, an agricultural expert, I continued private training at Tema High School.

Unlike a boy who creates headlines in the UK, who claimed that the Ghana’s education system did not meet the standard, I thought it was demanding.

I was considered academically gifted in the UK despite my troubled ways, but it was actually difficult in Ghana. Students of my age were far ahead in subjects such as mathematics and science.

The rigor of the Gan system pushed me to study more stronger than I had in London.

The result? I earned five GCSE with class C and above – what once seemed impossible.

In addition to learning achievements, the Honorable Society instilled in values that remained with me for life.

Respect for the elders was not necessary. You met you older than you, regardless of whether you knew or not.

Ghana didn’t just make me more disciplined and respectful – it made me fearlessly.

Football played a big role in this transformation. I played in parks that were often a solid green clay with loose pebbles and stones, with two square gates made of wood and strings.

It was a distant cry from neatly supported sites in England, but it strengthened me the way I couldn’t imagine – and no wonder some of the greatest football players who saw in the English Premier League came from West Africa.

Gets the image

Gets the imageThe aggressive style that played in Ghana was not only about skill – it was about stability and endurance. Getting struggling with rough land meant to take away, pollen yourself and continuing.

Every Sunday I played football on the beach – although I was often late because none of my uncles would allow me to stay home and not attend church.

Those services felt that they lasted forever. But it was also a testimony to Ghana as a nation that fears God where faith is deeply laid in everyday life.

The first 18 months were the most difficult. I was outraged by restrictions, cases, discipline.

I even tried to steal my passport to go back to London, but my mother was ahead of me and hid it well. There was no escape.

My only choice was to adapt. Somewhere along the way, I stopped seeing Ghana in prison and started seeing it as a happy home.

I know about a few others as I, who were sent to Ghan’s parents living in London.

Michael Ado was 17 when he arrived at acra to school in the 1990s, calling his experience as “bitter”. He stayed until he was 23 years old and now lives in London, working as a test body.

His main complaint was loneliness – he missed his family and friends. There was a time of anger about his situation and the complications of the feeling of incomprehensible.

This greatly followed from the fact that his parents did not teach him and siblings none of the local languages when grown in London.

“I didn’t understand the GA. I didn’t understand TWI. I didn’t understand Pidgina,” the 49-year-old guy tells me.

It made him feel vulnerable in his first two and a half years, he said, for example, about being listed to those who increase the prices because he seemed alien.

“Anywhere I went, I had to make sure I went with someone else,” he says.

But as a result, he felt on TWI, and in general he believed that the positives exceeded the negatives: “It made me a man.

“My experience of Ghana has ripe me and changed me for the better, helping me identify myself with who I am, as Gan, and enshrined my understanding of my culture, prerequisites and family history.”

Mark Wilberfors

Mark WilberforsI can agree with that. In the third year, I fell in love with culture and even stayed almost two years after passing my gcses.

I developed a deep assessment of local food. Still in London I never thought twice about what I ate. But Ghana had food not only food – each dish had its own story.

I am obsessed with “waakye”-stroke made from rice and black-eyed peas, often cooked with millet leaves, which gives it a characteristic purple brown color. Usually it is served with fried plantain, hot black pepper “Shyto”, boiled eggs, and sometimes even spaghetti or fried fish. It was the final comfortable food.

I liked the music, the warmth of the people and the sense of community. I’m no longer just “stuck” in Ghana – I flourished.

My mother, Wilberfors’ patience, died recently, and with her loss, I was deeply reflecting on the decision she took all years ago.

She saved me. If she hadn’t cheated me to stay in Ghana, the chances of being convicted and even serving a term in prison would be extremely high.

I continued to go to the North Western London College at the age of 20 to study production and communications in the media before you come to BBC Radio 1xtra through the mentoring scheme.

The guys with whom I used to hang out in the northwest of London did not get the second chance I did.

Ghana has reworked my thinking, my values and my future. This turned the wrong threat to a responsible person.

Although such an experience may not work for everyone, it gave me education, discipline and respect that I needed to enter society when I returned to England.

And for this I owe my mother, uncle and the country that saved me forever.

Mark Wilberfors is a Freelancer journalist based in London and Acra.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC