Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

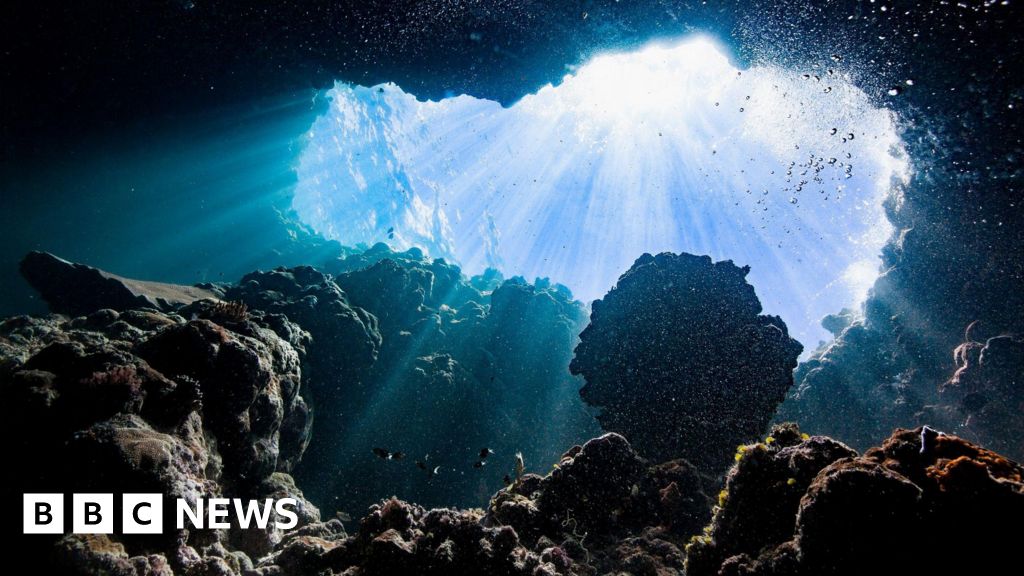

Scientists who recently discovered that lumps of metal on the dark seabed create oxygen have announced plans to explore the deepest parts of Earth’s oceans to understand the amazing phenomenon.

Their mission could “change the way we look at the possibility of life on other planets,” the researchers say.

The initial discovery baffled marine scientists. It used to be thought that plants could only produce oxygen in sunlight – in a process called photosynthesis.

When oxygen – a vital component of life – is formed in the dark by clumps of metal, researchers believe that this process may be happening on other planets, creating an oxygen-rich environment where life can flourish.

Lead researcher Professor Andrew Sweetman explained: “We are already talking to NASA experts who believe that dark oxygen could change our understanding of how life can exist on other planets without direct sunlight.

“We want to go there and find out exactly what’s going on.”

The initial discovery caused a worldwide scientific controversy – it was criticism of findings from some scientists and from deep-sea mining companies that plan to extract precious metals from the nodules of the seabed.

When oxygen is produced at these extreme depths, in total darkness, it raises questions about what life could survive and thrive on the seabed, and what impact mining might have on marine life.

That means seabed mining companies and environmental groups, some of whom have argued the findings suggest seabed mining plans should be shelved, will be watching this new investigation closely.

It is planned to work in places where the depth of the seabed exceeds 10 km (6.2 mi), using remotely controlled underwater equipment.

“We have instruments that can reach the deepest parts of the ocean,” Professor Sweetman explained. “We’re pretty sure we’re going to see it happen somewhere else, so we’re going to start figuring out what’s causing it.”

Some of these experiments, conducted in collaboration with NASA scientists, will aim to understand whether this same process could allow microscopic life to flourish beneath the oceans found on other planets and moons.

“If there is oxygen,” said Professor Sweetman, “there may be microbial life that will take advantage of it.”

The first, biologically unclear results were published last year in the journal Nature Geoscience. They arrived from several expeditions to the deep-sea area between Hawaii and Mexico, where Professor Sweetman and his colleagues sent sensors to the sea floor – to a depth of about 5 km (3.1 miles).

This area is part of a large area of seafloor covered with natural metallic nodules that form when seawater-soluble metals collect on fragments of shells or other debris. It is a process that takes millions of years.

The sensors the team deployed repeatedly indicated that oxygen levels were rising.

“I just ignored it,” Professor Sweetman told BBC News at the time, “because I was taught that oxygen was only produced through photosynthesis.”

Eventually, he and his colleagues stopped ignoring their testimony and instead decided to understand what was going on. Experiments in their lab – with the nodules the team collected submerged in beakers of seawater – led the scientists to conclude that the metal lumps were creating oxygen from the seawater. They discovered that the nodules generate electrical currents that can split (or electrolyze) seawater molecules into hydrogen and oxygen.

Then there was a backlash in the form of rebuttals posted online by scientists and seabed companies.

One critic, Michael Clarke of the Metals Company, a Canadian deepwater mining company, told BBC News that the criticism focused on “the lack of scientific rigor in the design of the experiments and the collection of data”. Essentially, he and other critics argued that there was no oxygen generation – only bubbles produced by the equipment during sample collection.

“We have ruled out that possibility,” replied Professor Sweetman. “But these (new) experiments will serve as proof.”

This may sound like a niche technical argument, but several multi-billion dollar mining companies are already exploring the possibility of extracting tons of these metals from the seabed.

The natural deposits they are targeting contain metals vital to making batteries, and demand for these metals is growing rapidly as many economies switch from fossil fuels to, for example, electric cars.

The race to extract these resources has raised concerns among environmental groups and researchers. More than 900 marine scientists from 44 countries signed the petition highlighting environmental risks and calling for a moratorium on mining.

Speaking about his team’s latest research mission at a press conference on Friday, Professor Sweetman said: “Before we do anything, we need to understand – as best we can – the (deep-sea) ecosystem.

“I think the right decision will be to wait before we decide whether it’s the right thing to do as a global society.”