Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

BBC

BBCWhen Mzwandile Mkwai was lowered into a South African mine in a red metal cage attached to a lift above the ground, the first thing that struck him was the smell.

“Let me tell you something,” he tells the BBC, “those bodies really smelled.”

When he returned home later that day, he told his wife that he could not eat the meat she had cooked.

“This is because when I spoke to the miners, they told me that some of them had to eat other (people) in the mine because they could not find food. And they also ate cockroaches,” he said during a telephone conversation. from his house.

Allegations that the miners were eating human flesh to survive were also made by other miners rescued in December in statements submitted to the high court.

Mkwai, an ex-convict known locally as Shasha, lives in Huma township, which was located near an abandoned mine in Stillfontein. A 36-year-old man who served seven years in prison for robbery volunteered to come down to help with the rescue.

“I am being rehabilitated by correctional services and I volunteered because people in our community were looking for help for their children and siblings.

“The rescue company said they didn’t have anyone willing to go down. So my friend Mandla and I agreed to volunteer to help our brothers get to the surface and pick up the bodies of the dead.”

But as much as he wanted to help, the 25-minute journey down the 2 km (1.2 mi) deep shaft filled him with terror.

AFP

AFPThe crane occasionally stopped and moved, leaving him dangling in the dark. Descending into the mine, he was shocked by what he saw.

“There were a lot of bodies, over 70 bodies and about 200 or so people who were dehydrated.

“I felt very weak when I saw them, it was painful to see. But Mandl and I decided that we need to be strong and not show them how we feel to motivate them.”

This story contains video that some people may find upsetting.

The miners, who had been waiting for help for months, gave them a hero’s welcome.

“They were very, very happy,” he says.

The miners were stuck there following a nationwide police operation to stop illegal mining at the abandoned sites, which were closed as the industry – once the backbone of the country’s economy – shrank.

It was no longer profitable for multinational mining corporations to operate in many places, but the promise of still finding gold deposits was a magnet for many desperate people – especially undocumented migrants.

Thousands of shafts were abandoned.

In November, police stepped up efforts at the Bufelsfontein mine in Stilfontein, surrounding the mine entrance and refusing food and water.

Before the rescue operation began on Monday, the local population tried to take matters into their own hands, lowering a rope down the mine to try to pull some of the men out.

They also sent messages and told the miners that help was coming.

“So when we got there, they were already waiting for the crane. Now, when they see us, they see us as their presidents, their messiahs: people who came from outside into the hole to help them come to the surface.”

Police say illegal diggers could always go out on their own, but refused to do so for fear of arrest. But Mkwai disagrees: “It’s a lie that people didn’t want to come out. These people were desperate for help, they were dying.”

The BBC saw dozens of rescued men at the mine site on Tuesday.

They looked emaciated, their bones visible through their clothes. Some of them could barely walk, they had to be helped by medical personnel.

In statements filed in the high court, the illegal miners described in vivid detail the slow and agonizing death of their peers. Many are said to have starved to death.

“From September to October 2024, the lack of even basic means of subsistence was absolute, and survival became a daily struggle against hunger,” said one miner.

Mkwai says the people he rescued were so weak that a rescue cage designed to carry only seven healthy adults could only hold 13 of them.

“They were very dehydrated and losing weight, so we managed to fit more into the cage because they wouldn’t have lasted another two days in the hole. They would be dead if we didn’t get them out as soon as possible.”

Volunteers were also engaged in raising the bodies of the dead.

“The rescue services gave us bags and told us to put the bodies in them and carry them out to the cage, which we did with the help of some miners.”

Initially, it was planned that the rescue operation would last at least a week, but after three days the volunteers announced that there was no one left underground.

Authorities sent a camera into the mine to do a final sweep. They say now the mine will be sealed forever.

But the experience had a profound effect on Mkwai.

At one point during the call, he asks for the question to be repeated, explaining that his hearing became impaired after he went down the mine, presumably due to the pressure.

But what he witnessed had the greatest impact.

“I have to tell you that I am injured. I will never forget the sight of these people for the rest of my life.”

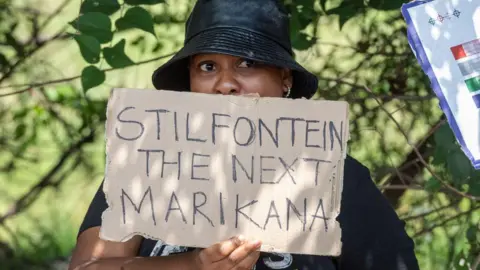

For activists and trade unions that help society, the death of 87 people in the mine is equal to a “massacre” committed by the authorities.

The use of the emotional word has drawn comparisons with 34 striking miners shot dead by police in Marikanaapproximately 150 km (93 mi) from Stilfontein, in 2012.

But this time the trigger was not pulled. Instead, it appears that many of the men starved to death.

The authorities deny that they are responsible.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe government initiated a crackdown on illegal mining in December 2023 through Operation Vala Umgodi (meaning ‘close the hole’ in Izulu).

Abandoned mines have been taken over by gangs, often led by ex-employees, who sell what they find on the black market.

People were forcibly or voluntarily drawn into this illegal trade and forced to spend months underground digging for minerals. The government says illegal mining cost the South African economy $3.2bn (£2.6bn) in 2024 alone.

As part of the police operation, entry points to various abandoned mines were blocked, along with food and water supplies, to drive out the illegal miners, known locally as zama zamas (which translates as “take a risk”).

While Wala Umgodi has been largely successful in other provinces, the old Buffelsfontein gold mine has presented a unique challenge.

Before the police operation, most miners could only get underground through a makeshift pulley system operated by people on the surface.

But then they left the top of the mine when a large number of security personnel arrived in August, leaving those inside the mine alone.

Community members then stepped in to help, pulling several people up with ropes, but it was a long and difficult process.

Other difficult and dangerous exits were available, and in total nearly 2,000 surfaced – most of whom were arrested and remain in police custody.

Why the others did not come out is not clear – perhaps they were too weak or threatened by gang members in the mine – but they were left in desperate circumstances.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOf the 87 dead, only two have been identified, police said Thursday, explaining that the fact that many of them were undocumented migrants had complicated the process.

“We believe the government’s hands are covered in blood,” Magnificent Mndebele of the group Joint Action on Mining Affected Communities (Makua) told the BBC.

He claimed that the miners were not warned of what was about to happen before the police operation began.

In the past two months, Makua has been at the forefront of various legal battles initiated to force the government to first allow the supplies and then carry out the rescue operation.

The government’s accusation echoes earlier claims by families who said authorities killed their loved ones.

They took a tough stance after intensifying the operation. In November, one minister, Khumbuzo Ntschauheni, made the infamous statement during a press briefing that they were going to “smoke them out”.

The state refused to allow the delivery of food or anyone to help get the miners, only after several successful lawsuits.

In November, small portions of instant corn and water made it into the mine, but in a court filing, one miner said it was not enough for the hundreds of people below, many of whom were too weak to even chew and swallow them.

More food was delivered in December, but again this could not sustain the people.

Given that the operation to retrieve the men and bodies lasted just three days, Mr Mndebele finds it hard to see why it could not have been done sooner when it was clear there was a problem.

“We’re disappointed with our government, frankly, because this help came too late.”

Although the government has yet to officially respond to the allegations, police have vowed to continue wider operations to clear the country of unused landmines until May this year.

Speaking to reporters in Stilfontein on Tuesday, Mining Minister Gwede Montashe was unapologetic. He said the government would step up its fight against illegal mining, which he described as a crime and an “attack on the economy”.

Police Minister Senzo Mchunu was a little more conciliatory on Thursday.

“I understand and accept that this is an emotional issue. Everyone wants to judge … but it will help all of us South Africans to wait for the pathologists to do and complete their work,” he said.

The police justified their actions by saying that providing the miners with food would “allow crime to flourish”.

Illegal miners are accused of facilitating crime in the communities where they work.

A number of stories have been published in local media linking zama zamas to various rapes and murders.

But for Mkwai, who has put his own safety ahead of helping the miners, the people at Stilfontein Mine were just trying to make a living.

“People were abseiling 2km and risking their lives to put food on the table for their families.”

He said he wanted the government to issue licenses to artisanal miners forced into abandoned mines due to South Africa’s high unemployment rate.

“If your children are hungry, you won’t think twice about going there because you have to feed them. You will risk your life to put food on the table.”

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC